At least half of the cases of bipolar disorder begin in childhood or adolescence. How do you decide whether a young patient’s symptoms indicate bipolar disorder? Read this CME Brief Report to learn about reliable tools and methods to identify bipolar disorder in pediatric patients.

Find more articles on this and other psychiatry and CNS topics:

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders

Find more articles on this and other psychiatry and CNS topics:

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders

CME Background Information

Supported by an educational grant from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Participants may receive credit by reading the activity, correctly answering the posttest questions, and completing the evaluation.

Objective

After completing this educational activity, you should be able to:

- Correctly diagnose bipolar disorder in pediatric patients, particularly during episodes of depression

Financial Disclosure

The faculty for this CME activity and the CME Institute staff were asked to complete a statement regarding all relevant personal and financial relationships between themselves or their spouse/partner and any commercial interest. The CME Institute has resolved any conflicts of interest that were identified. No member of the CME Institute staff reported any relevant personal financial relationships. Faculty financial disclosures are as follows:

Dr Singh has received grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, Neuronetics, Stanford Child Health Research Institute, and Johnson & Johnson and is a member of the advisory board for Sunovion.

The Chair for this activity, Melissa P. DelBello, MD, MS, is a consultant for Akili, CMEology, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Neuronetics, Pfizer, Sunovion, Supernus, and Takeda and has received grant/research support from Amarex, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Otsuka, Shire, Sunovion, Supernus, and Lundbeck.

Accreditation Statement

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians and other health care providers.

Credit Designation

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., designates this enduring material for a maximum of 0.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

The American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) accepts certificates of participation for educational activities certified for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ from organizations accredited by ACCME or a recognized state medical society. Physician assistants may receive a maximum of 0.5 hours of Category 1 credit for completing this program.

To obtain credit for this activity, study the material and complete the CME Posttest and Evaluation.

Release, Review, and Expiration Dates

This brief report activity was published in December 2018 and is eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ through December 31, 2020. The latest review of this material was October 2018.

Statement of Need and Purpose

Clinicians often base their diagnoses of pediatric bipolar disorder on clinical observations rather than using assessment tools. Both the diagnostic criteria that were written for adults and the frequent overlap of symptoms with other conditions can complicate the diagnostic process. Clinicians are not comfortable with treatment options for pediatric bipolar depression, and few up-to-date guidelines and rigorous clinical trial data in this population are available. Providers are failing to ensure coordination of continuity of care from pediatric to adult facilities. Clinicians need information on the presentation of pediatric patients with bipolar disorder, on the characteristics that distinguish this disorder from other conditions, and on clinical tools to help them conduct a differential diagnosis. Clinicians also need information about the safety and efficacy of treatments that have been investigated in pediatric bipolar depression, the educational needs of patients and their parents, and how to coordinate a smooth transition from pediatric to adult mental health services. This activity was designed to meet the needs of participants in CME activities provided by the CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., who have requested information on bipolar disorder in pediatric populations.

Disclosure of Off-Label Usage

Dr Singh has determined that, to the best of her knowledge, no investigational information about pharmaceutical agents that is outside US Food and Drug Administration–approved labeling has been presented in this activity.

Review Process

The entire faculty of the series discussed the content at a peer-reviewed planning session, the Chair reviewed the activity for accuracy and fair balance, and a member of the External Advisory CME Board who is without conflict of interest reviewed the activity to determine whether the material is evidence-based and objective.

Acknowledgment

This brief report is derived from the planning teleconference series “Overcoming Challenges in Diagnosis and Depression Management in Pediatric Bipolar Disorder,” which was held in June and July 2018, and supported by an educational grant from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. The opinions expressed herein are those of the faculty and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the CME provider and publisher or the commercial supporter.

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Pediatric Mood Disorders Program, Stanford University School of Medicine, California

Pediatric bipolar disorder is a significant health problem and an area of intense clinical and research interest.1 The average age at onset is 18 years;2 however, bipolar disorder can emerge at any time. Half to two-thirds of the time, the disorder emerges in childhood or adolescence.3 Pediatric-onset bipolar disorder is often complicated and chronic, and, compared with adult-onset patients, those whose bipolar disorder emerges before the age of 18 years are more likely to experience comorbid anxiety, ≥10 lifetime mood episodes, alcohol use disorder, and suicidality.4 Indeed, more than 75% of patients who had pediatric bipolar disorder have reported lifetime suicidal ideation,1 which underscores the importance of correctly identifying bipolar disorder in pediatric patients, particularly during episodes of depression.

Bipolar disorder can cause substantial distress for young people. For example, 2 patients described their feelings in the following ways:

PATIENT PERSPECTIVES

PATIENT PERSPECTIVES

“I am really feeling sad and depressed and lousy about myself… I still feel like I want to kill myself. I am really sad but I just want help to feel happy again. The reason I feel so bad is because I can’t sleep at night. And dad yells at me to just sleep at night. But, I can’t control it. It is not me that does control it. I don’t know what controls it, but it is not me.” –Blake, age 7 years14

“I felt like nobody was on my side. That’s kind of how I always felt. . . . Rather than try to calm down and tell them how I feel, I would just show it through emotion: I would just cry or yell. . . . I can’t think straight, I guess, when I’m agitated. I just start yelling, or I start crying. You just can’t think straight.” – Jennifer, age 10 years15

Clinical Presentation of Pediatric Bipolar Disorder

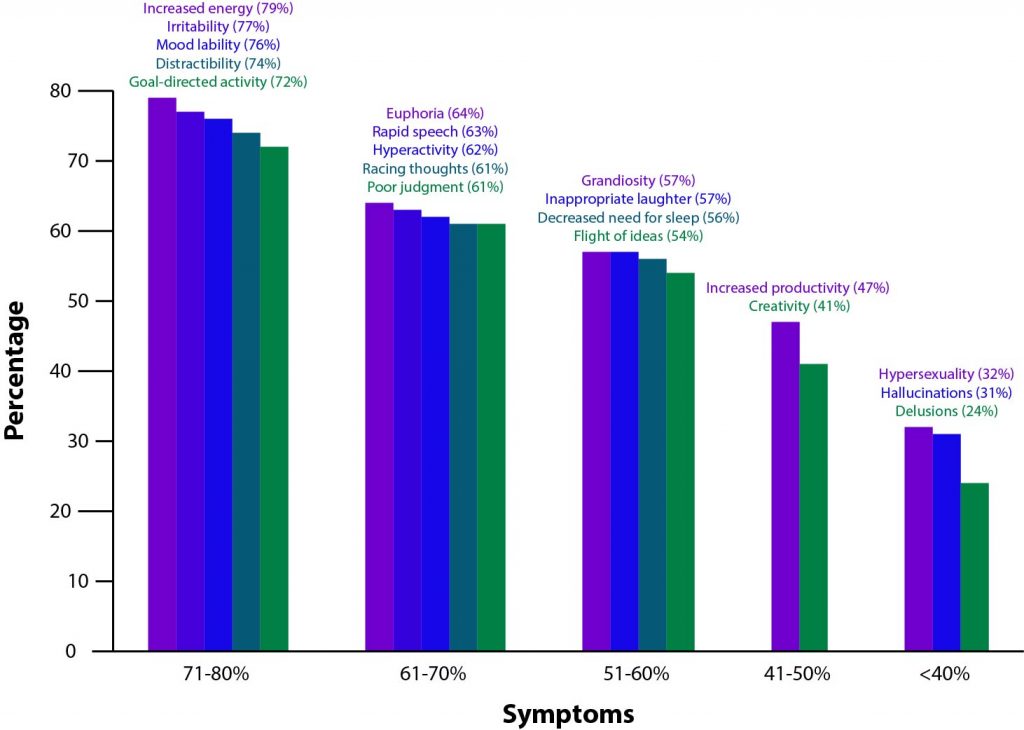

In some instances, the younger the patient, the more likely the initial episode will be depression, which may lead to the patient being misdiagnosed with major depressive disorder.5 Clinical characteristics such as a family history of bipolar disorder and a younger age at onset may indicate a possible risk for bipolar rather than unipolar depression,6 and considering such clinical risk factors may assist clinicians in making an accurate diagnosis before mania symptoms emerge. With any presentation of depression, clinicians should assess patients for mania or hypomania. Pediatric bipolar disorder may be difficult to detect because moodiness and irritability are common in childhood and adolescence, but symptoms of irritability, rage, mood lability, or unusual sleep habits, activity levels, or behavior should prompt a clinician to assess patients for bipolar disorder.7 Diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorders are available,2 but clinicians must be aware that symptoms of depression or mania may present differently in pediatric patients than in adults. Frequencies of various diagnostic symptoms among youth with bipolar disorder are shown in AV 1.8

Depressive symptoms. Pediatric bipolar depression presents similarly to adult bipolar depression in that most youth spend substantially more of their time depressed than manic.9 Some individuals with bipolar disorder will experience full depressive episodes, meaning that they present with ≥ 5 depressive symptoms, one of which is a mood issue accompanied by impaired function.2 This diagnosis translates to 2 weeks of irritable or depressed mood for most of the day nearly every day, plus insomnia or hypersomnia, markedly decreased interest in activities that are normally fun for a child, feelings of worthlessness or low self-esteem, fatigue or loss of energy, difficulty thinking or concentrating, significant weight loss or gain (≥5% change), psychomotor changes, and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide ideation.2 However, a full depressive episode is not required for a diagnosis of bipolar disorder,2 and children may experience subsyndromal depressive episodes or symptomatology.10 Differences that do occur between symptom presentations in children and adults may be attributed to a child’s physical, emotional, cognitive, and social developmental stages.11

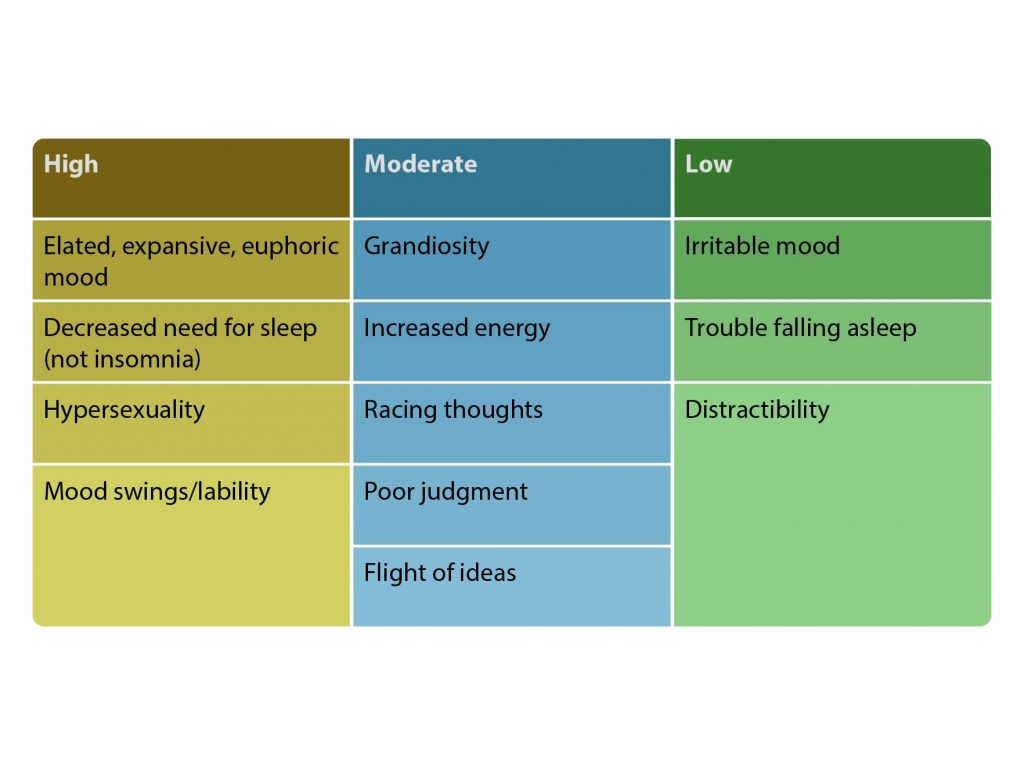

Manic symptoms. The DSM-52 defines the components of mania as episodes of elevated or irritable mood lasting at least 1 week that occur most of the day, almost every day; characteristic concurrent symptoms; and resulting impairment. Manic symptoms should not be attributable to a substance but could emerge during antidepressant treatment. Manic episodes can be superimposed on other disorders and the overlapping symptoms worsen during mania. Although these criteria seem straightforward, due to a lack of systematic research, there is debate among researchers and clinicians about the core symptoms of hypomania or mania in children and how they differ from adult presentations.12 According to a systematic review12 of studies that directly compared the phenomenology of mania in different age groups, irritability and aggression are key features of childhood-onset bipolar disorder; activity/energy and elation/euphoria are the most prominent symptoms in adolescent-onset bipolar disorder; and pressured speech and changes in cognition are most characteristic of adult-onset bipolar disorder. Elation/euphoria is also a common symptom of mania in children with bipolar disorder.12

Mixed episodes in pediatric bipolar disorder. Mixed episodes—eg, mania and major depression, hypomania and major depression, mania and dysthymia, or cyclothymia—are common and have been validated in pediatric bipolar depression. Among youth with bipolar disorder, mixed states are more common than either manic or depressive episodes, and polarity changes occur often (mean=12 times/year).9

A 4-year prospective study13 followed youth (N=86) diagnosed with mania at baseline. Participants spent 37% of weeks in the follow-up period with mixed episodes.13 Mixed presentations in youth with bipolar disorder have been linked to increased likelihood of attempting suicide.13

Diagnosing Pediatric Bipolar Disorder

Distinguishing unipolar depressive episodes from bipolar depression is possible but often occurs in the long term;16 patients with bipolar disorder can wait an average of 10 years before receiving an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment regimen.17 Manic symptoms in children often show atypical features, and hypomanic episodes are often not seen as impairing because over 70% of children with the disorder have been found to have mood and energy shifts several times a day. Youth with bipolar disorder also have a high rate of comorbid psychiatric conditions that can complicate the diagnostic process due to symptom overlap.17 Clinicians can improve their recognition of bipolar disorder in pediatric patients by taking a thorough family history and using structured diagnostic interviews, rating scales, and self-reports.

Family history. Because pediatric patients often present with subthreshold symptoms or in a possible prodromal state, or with symptoms similar to those of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and/or depression, a family history of bipolar disorder could be a critical piece of information indicating that a pediatric patient may be predisposed to a future diagnosis of bipolar disorder.18,19 For example, the Course and Outcome of Bipolar in Youth (COBY) study20 sought to determine predictors of outcome in youth aged 7 to 17 years with bipolar spectrum disorders over a period of 2 years. Researchers included patients who were experiencing clinically relevant bipolar symptoms but did not meet the diagnostic criteria for BP-I or BP-II. They categorized these patients with a diagnosis of BP not otherwise specified (BP-NOS) and provided a clear definition of symptoms in this category that had been lacking in the DSM. This study defined BP-NOS as ≥4 hours of mania-like symptoms in a 24-hour period, for ≥4 cumulative days. The investigators found high rates of first- and second-degree relatives with histories of mania (28%–33%) and depression (68%–70%) among all study participants.20 Furthermore, a study by Birmaher and colleagues21 found that, among children aged 6 to 18 years, rates of bipolar spectrum disorders were 14 times higher among those whose parents had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder than among those without a parental history. In times of diagnostic uncertainty, a family history of bipolar disorder can be a helpful indicator of possible bipolarity.

CASE PRACTICE QUESTION

CASE PRACTICE QUESTION

Case 1. Joy is a 15-year-old sophomore who began psychotherapy for persistently low mood 6 months ago. After experiencing no response, she was prescribed an antidepressant 1 month ago. Now she reports that for the past 2 to 3 days she has gone without any sleep, “running around like an Energizer bunny,” and has experienced distractibility from racing thoughts, rapid speech, and rapid mood swings. She cannot understand why she feels happy and sad at the same time and describes herself as being “out of control.” Which of the following factors, besides the symptoms that emerged with antidepressant therapy, is most likely to predict a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder in Joy?

- Lack of response to psychotherapy

- A family history of bipolar disorder in a first-degree relative

- A blood test confirming hyperthyroidism

- Suicidal ideation

DISCUSSION OF CASE PRACTICE QUESTIONS

DISCUSSION OF CASE PRACTICE QUESTIONS

Preferred response: b.

Explanation: Joy began treatment for a depressive episode but now is showing signs of mania. Clinicians must ask questions about the psychiatric history of biological family members of the patient.

AV 2. Symptom Specificity for Pediatric Bipolar Disorder

Based on Youngstrom et al10.

Overlapping symptoms. A major challenge in diagnosing bipolar disorder in pediatric patients is that patients may present with nonspecific symptoms that indicate co-occurring conditions or overlapping mood states (AV 2).10 For example, manic symptoms can overlap with depression in a mixed state, and symptoms such as irritability, distractibility, pressured speech, sleep changes, and mood swings may indicate the presence of bipolar disorder or one of a number of conditions commonly co-occurring with bipolar disorder, including ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and anxiety.10 The most common co-occurring condition in youth with bipolar disorders is ADHD, with comorbidity rates ranging from 60% to 90%.22 Due to symptom overlap, ADHD may be misdiagnosed as bipolar disorder,18 but clinicians can clarify the diagnosis by discerning whether symptoms are chronic or episodic10 and by looking for bipolar disorder symptoms that are more indicative of this disorder than ADHD, such as elated mood, grandiosity, or racing thoughts.23

CASE PRACTICE QUESTION

CASE PRACTICE QUESTION

Case 2. Twelve-year-old Blue was taken to see a psychiatrist after his parents told him they were getting a divorce. Blue complained of sad mood, feeling bored with things that were previously fun, and having frequent temper outbursts. When his parents separated, Blue began defying teachers and got involved in confrontations with other children. Blue’s grades began to suffer from not turning in homework. He started having trouble sleeping, often waking up as much as 4 times in the night. He also had no appetite and had stomach aches, stopped playing soccer due to lack of energy, and lost interest in attending his after-school activities. Which of the following choices would be a helpful first step in determining whether Blue meets criteria for bipolar or unipolar depression?

- Call Blue’s pediatrician.

- Inquire about a family history of ADHD.

- Assess for the presence of mania or hypomania symptoms in Blue’s lifetime.

- Order an MRI.

DISCUSSION OF CASE PRACTICE QUESTION

DISCUSSION OF CASE PRACTICE QUESTION

Preferred response: c.

Explanation: Blue should be assessed for a lifetime presence of mania. Often when youth present with depressive symptoms, clinicians fail to assess for manic and hypomanic symptoms and, therefore, miss a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Every child that comes in to be evaluated for any mood symptoms should have a thorough screening for both depression and mania at every visit.

Diagnostic Tools

In order to accurately diagnose depression in youth, whether bipolar or unipolar, clinicians should evaluate patients on multiple levels using a variety of assessment tools. For the first level of evaluation, the clinician should use structured interviews such as the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS)24 or the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA)25 to obtain a comprehensive and detailed assessment of the patient’s symptoms, both currently and over time.

The K-SADS is a comprehensive diagnostic tool but requires training and takes 2 to 3 hours to administer. Substance use is common among patients with bipolar disorder and must be identified; the K-SADS assesses substance abuse in addition to affective, psychotic, anxiety, and behavioral disorders and can be used as part of a comprehensive assessment.

Obtaining a family history is also critical, and clinicians can use the Family Interview for Genetic Studies (FIGS)26 or the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria (FH-RDC).27 If these structured assessments for family history are not available, the clinician can simply draw a family pedigree showing the patient’s first-, second-, and possibly third-degree relatives and then ask about each family member. Sometimes, relatives are unable to provide reliable information about a diagnosis but can describe examples of symptoms of depression or mania if asked specifically. In this way, clinicians can obtain a more comprehensive understanding of whether a family history of bipolar disorder exists.

In the second level of evaluation, the clinician should address dimensional symptoms. Symptom severity scales such as the Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS-R) or the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) may be used.28 The CDRS-R assesses severity of depression and change in depressive symptoms via interviews with the child and parent. The YMRS assesses manic symptoms based on the patient’s subjective report of his or her clinical condition.

Self-report scales. Self-report scales can be useful for prompting a detailed evaluation by a specialist, but sometimes they may be unreliable depending on a child’s capacity for insight. Self-report scales used in both clinical and research settings for screening manic and/or depressive symptoms include the General Behavioral Inventory29 (GBI); the 7 Up 7 Down Inventory30 (7U7D), which is an abbreviated version of the GBI; the Childhood Depression Inventory (CDI);31 and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).32

Conclusion

Bipolar disorder is a significant health problem that presents differently in children and adolescents versus in adults. Clinicians must employ thorough, comprehensive assessments including structured interviews, rating scales, and self-report scales to aid in making an accurate diagnosis of pediatric bipolar disorder. This process helps to ensure that patients receive appropriate treatment of bipolar depression early on, potentially reducing the risk for suicidality, relapse, and impairment. If not diagnosed accurately and treated adequately, bipolar disorder may become a debilitating illness. Patients’ parents can be directed to reliable resources for more education about bipolar disorder and support, such as the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, National Alliance on Mental Illness, and Mental Health America.

Clinical Points

- Systematically assess for manic and depressive symptoms and episodes in all youth presenting with mood problems—incorporating assessment tools—both at baseline and over time.

- Assess for family history of bipolar disorder, inclusive of mania/hypomania symptoms, especially in first- and second-degree relatives.

- Look for symptoms with high specificity for bipolar disorder, especially those with an episodic nature, to distinguish the condition from disorders with overlapping symptoms.

To learn about managing bipolar disorder in children and adolescents, see the other activity in this series, Treating Bipolar Disorder in Pediatric Patients and Educating Patients and Parents, by Melissa P. DelBello, MD, MS.

Find more articles on this and other psychiatry and CNS topics:

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders

Abbreviations

ADHD = Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

BP I = bipolar I disorder

BP II = bipolar II disorder

CDI = Childhood Depression Inventory

CDRS-R = Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised

DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

FH-RDC = Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria

FIGS = Family Interview for Genetic Studies

GBI = General Behavioral Inventory

K-SADS = Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia

NOS = not otherwise specified

PAPA = Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment

PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire

7U7D = 7 Up 7 Down Inventory

YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale

References

- Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, et al. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(10):1139–1148. PubMed doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1139

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Fifth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Chang K. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric bipolar depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(1):73–80. PubMed

- Holtzman JN, Miller S, Hooshmand F, et al. Childhood-compared to adolescent-onset bipolar disorder has more statistically significant clinical correlates. J Affect Disord. 2015;179:114–120. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.019

- Bowden CL. Strategies to reduce misdiagnosis of bipolar depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(1):51–55. PubMed doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.1.51

- Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Vazquez GH, et al. Age at onset versus family history and clinical outcomes in 1,665 international bipolar-I disorder patients. World Psychiatry. 2012;11(1):40–46. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.006

- Kowatch RA. Diagnosis, phenomenology, differential diagnosis, and comorbidity of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(suppl E1):1-1.

- Van Meter AR, Burke C, Kowatch RA, et al. Ten-year updated meta-analysis of the clinical characteristics of pediatric mania and hypomania. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(1):19–32. PubMed doi:10.1111/bdi.12358

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, et al. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):795–804. PubMed doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08101569

- Youngstrom EA, Birmaher B, Findling RL. Pediatric bipolar disorder: validity, phenomenology, and recommendations for diagnosis. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(1p2):194–214. PubMed doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00563.x

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Walshaw PD, et al. A cognitive vulnerability-stress perspective on bipolar spectrum disorders in a normative adolescent brain, cognitive, and emotional development context. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18(4):1055–1103. PubMed doi:10.1017/S0954579406060524

- Ryles F, Meyer TD, Adan-Manes J, et al. A systematic review of the frequency and severity of manic symptoms reported in studies that compare phenomenology across children, adolescents and adults with bipolar disorders. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2017;5(1):4. PubMed doi:10.1186/s40345-017-0071-y

- Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, et al. Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(5):459–467. PubMed doi:10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.459

- Carmichael M. Growing Up Bipolar: Max’s World. https://www.newsweek.com/growing-bipolar-maxs-world-90351. May 2008. Accessed November 2018.

- Landau E. Growing Up Bipolar: “Nobody was on my side.” http://www.cnn.com/2010/HEALTH/08/30/bipolar.kids/index.html. August 2010. Accessed November 2018.

- Diler RS, Goldstein TR, Hafeman D, et al. Distinguishing Bipolar Depression from Unipolar Depression in Youth: Preliminary Findings. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(4):310–319. PubMed doi:10.1089/cap.2016.0154

- Singh T. Pediatric bipolar disorder: diagnostic challenges in identifying symptoms and course of illness. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2008;5(6):34–42. PubMed

- Chang KD. Diagnosing Bipolar Disorder in Pediatric Patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(2):SU17023TX1C. PubMed doi:10.4088/JCP.SU17023TX1C

- Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Strober MA, et al. Course of subthreshold bipolar disorder in youth: diagnostic progression from bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(10):1001–1016.e3. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.005

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, et al. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(2):175–183. PubMed doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.175

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, et al. Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(3):287–296. PubMed doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.546

- Joshi G, Wilens T. Comorbidity in pediatric bipolar disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18(2):291–319, vii–viii. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.chc.2008.12.005

- Geller B, Tillman R. Prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar I disorder: review of diagnostic validation by Robins and Guze criteria. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl 7):21–28. PubMed

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (k-sads-pl): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. PubMed doi:10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021

- Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, et al. Test-Retest Reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(5):538–549. PubMed doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8

- Maxwell E. The family interview for genetic studies manual (Intramural Research Program, Clinical Neurogenetics Branch). Washington: National Institute of Mental Health; 1992.

- Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, et al. The family history method using diagnostic criteria. Reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34(10):1229–1235. PubMed doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770220111013

- Yee AM, Algorta GP, Youngstrom EA, et al; LAMS Group. Unfiltered Administration of the YMRS and CDRS-R in a Clinical Sample of Children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44(6):992–1007. PubMed doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.915548

- Depue RA, Slater JF, Wolfstetter-Kausch H, et al. A behavioral paradigm for identifying persons at risk for bipolar depressive disorder: a conceptual framework and five validation studies. J Abnorm Psychol. 1981;90(5):381–437. PubMed doi:10.1037/0021-843X.90.5.381

- Youngstrom EA, Murray G, Johnson SL, et al. The 7 up 7 down inventory: a 14-item measure of manic and depressive tendencies carved from the General Behavior Inventory. Psychol Assess. 2013;25(4):1377–1383. PubMed doi:10.1037/a0033975

- Smucker MR, Craighead WE, Craighead LW, et al. Normative and reliability data for the Children’s Depression Inventory. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1986;14(1):25–39. PubMed doi:10.1007/BF00917219

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. PubMed doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Save

Cite