ABSTRACT

Objective: To estimate the fiscal consequences of schizophrenia compared to the general US population using a “government perspective” fiscal analytic modeling framework capturing lost tax revenue and broader government costs in 2021.

Methods: Schizophrenia was modeled from age 23 using a cohort-based Markov chain with 6-week cycles, simulating the effect of antipsychotic treatment sequences on remission and relapse. Markov states were defined using efficacy and safety outcomes from short- and long-term clinical trials. Mortality was based on US lifetables, schizophrenia-related suicide, and cardiovascular risks. A semi-Markov model with annual cycles simulated the likelihood and costs of incarceration and homelessness in community-based individuals. Lifetime fiscal consequences were estimated conditionally to survival, remission/relapse status, and likelihood of socioeconomic outcomes. Costs and life years were discounted at 3.0% annually. Uncertainty was explored in 1-way and scenario analyses.

Results: Unemployment, disability, incarceration, homelessness, health care use, and productivity losses were more common in people living with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia was associated with a $1,540,042 per person lifetime fiscal loss to the government, with $56,707 per life year lived with schizophrenia. Health care costs represented 41.9% of the fiscal losses, 39.4% were due to criminal and homelessness costs, and 17.5% related to foregone tax revenue. Considering a 1.19% prevalence of schizophrenia, the estimated annual fiscal burden in the US was $173.6 billion.

Conclusions: The fiscal framework illustrates how schizophrenia influences taxation and government transfer payments over time. These findings can be used to augment cost-effectiveness analyses and inform stakeholders of the fiscal impact of schizophrenia to inform priority interventions.

J Clin Psychiatry 2023;84(5):22m14746

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Schizophrenia is a chronic and complex mental illness manifesting through positive symptoms such as hallucinations, negative symptoms like avolition or decreased ability to express emotion, in combination with disorganized thinking or speech.1,2 Persisting symptoms impact several domains of everyday functioning, including social interactions, academic achievements, vocational activities, and the ability of living independently.3–6 Despite its relatively low prevalence, schizophrenia accounts for 13.4 million years lived with disability, 1.7% of the annual global disability burden.7 Due to its early onset and severity, acute schizophrenia has been found to be the disease with the highest disability weight ratio (0.78, uncertainty interval 0.61 to 0.90).8

It is thought that 1.19% of the 258 million US adults (2021) have schizophrenia, approximately 3.1 million individuals.9 The annual societal cost per person living with schizophrenia (PLWS) in the US has been estimated to range from $17,569 to $55,373 in 2015.10,11 Given these figures, the estimated annual societal cost of schizophrenia ranges from $68 to $214 billion 2021 US dollars,12 approximately 0.3%–1.0% of the US gross domestic product.

The breakdown of schizophrenia’s economic burden varies among published burden of disease studies, but indirect costs, from PLWS and caregivers’ productivity losses, are unanimously reported as the largest cost component (48.9%–81.4%), followed by direct medical costs (19.5%–36.8%) and direct nonmedical costs such as legal, social benefits, and sheltering expenses (4.0%–18.2%).10,13 Cost-effectiveness analyses assessing the value of schizophrenia treatments can rightfully include broader economic consequences of the disease, albeit the large majority of these analyses solely focus on health system or third-party payer costs.14

The policy-led reduction of publicly funded mental health beds in the US has increased the pressure on community services and, since the mid-1970s, progressively contributed to mass incarceration15–17 and homelessness among PLWS.18 Because schizophrenia is associated with a substantial decrease in labor force participation and record high rates of incarceration and homelessness,17,19,20 disease externalities are likely to have an important impact on the broader economy and tax-funded resources utilization.

The goal of our research was to update existing estimates of the economic burden of schizophrenia21 and to quantify lifetime fiscal economic consequences not captured by other studies22 by utilizing a “government perspective” framework.23,24 The framework enabled estimating the monetary value of foregone tax contributions, and public expenses associated to justice, law enforcement, health care, and social support services in PLWS compared to the general US population.

METHODS

Modeling Framework

Failure to achieve and maintain schizophrenia symptoms remission (stable disease) has been associated with increased health care utilization and worse functional outcomes.25,26 Relapse can therefore impact the likelihood of social events and have monetary fiscal consequences for state and federal governments. An analytic model was developed in Microsoft Excel to simulate the lifetime economic burden of schizophrenia focusing on costs incurred by the US Government and Social Security Administration (SSA).23,24 A Markov trace simulated schizophrenia progression and estimated the annual proportion of individuals in remission or relapse (unstable disease), according to the efficacy of sequential antipsychotic (AP) treatments (Figure 1). An additional, semi-Markov process simulated transitions between the community, homelessness, and incarceration social states, conditionally to individual’s remission or relapse status. The annual fiscal costs of schizophrenia were compared to the fiscal costs of a cohort with the same age and gender unaffected by schizophrenia (general population). All calculations used the adult US population in 2021 (258,327,312),27 a 1.19% schizophrenia prevalence28 and a 66% proportion of males.29,30

Modeling Schizophrenia Progression

Simulating schizophrenia lifetime progression used a Markov model with a 6-week cycle, mimicking the duration of short-term clinical trials of APs. The model structure (Figure 1) departed from that described by Park and Kuntz,31 being expanded to consider a likely long-term distribution of AP treatments in the US. The model started at age 23,29,30 with individuals experiencing their first psychotic episode. Psychosis was modeled to remain undiagnosed for 74 weeks.29 Of the undiagnosed and/or untreated individuals, 74.1% were assumed to present active disease at any given time.32

Upon diagnosis, individuals started first-line treatment with a second-generation AP. Subsequently, people could remit and move to a stable/maintenance state, or discontinue treatment, remain unstable, and move to second-line treatment. The AP with the highest market share,33 not used as first-line treatment, was used as the second-line agent. On the following cycle, individuals could remain on the second-line AP, or discontinue/relapse, starting third-line AP therapy with another oral second-generation drug.33 Further discontinuation or relapse transitioned individuals to the long-term phase of the model with 40% not to receiving any schizophrenia treatment.34 Antipsychotic usage for the remaining 60.0% was informed by an analysis of Medicaid data,35 with 78.0% receiving an oral second-generation AP (same efficacy and safety as third-line oral AP), 16.8% a long-acting injectable AP (LAI), and 5.1% receiving clozapine. Those remaining on any AP treatment were assumed to achieve remission, facing the risk of relapse on the following cycle.36,37 The long-term phase of the model was assumed to repeat indefinitely until individuals’ death. General mortality was implemented using US lifetables.38 In PLWS, mortality accounted for the increased risk of suicide and AP-related cardiovascular risk.39,40 A detailed description of the inputs and methods used to model schizophrenia progression can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Modeling Social States Transition

A semi-Markov model with a 12-month cycle simulated transitions between mutually exclusive social states (community, incarceration, and homelessness) in the general US population and in PLWS (Figure 1). For simplicity, social states were modeled not to impact mortality. For example, incarcerated individuals had the same death rates as community-dwelling individuals.

All individuals started in the community social state where they could remain, transition to incarceration (prison or jail) or homelessness. Incarceration probability, duration, and recidivism were informed by nationwide US data and publications comparing the general population and PLWS. To account for time dependency in the Markov structure, incarcerated individuals were tracked using tunnel states.41 Tunnel states were also used to define a period of increased risk of reincarceration and homelessness in ex-convicts. We assumed that homelessness would last for 1 year, after which individuals would transition to a year-long ex-homeless state, being at higher risk of repeated homelessness and incarceration or could return to the community. The inputs and calculations used to model social state transitions are detailed in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Fiscal Consequences of Socioeconomic States

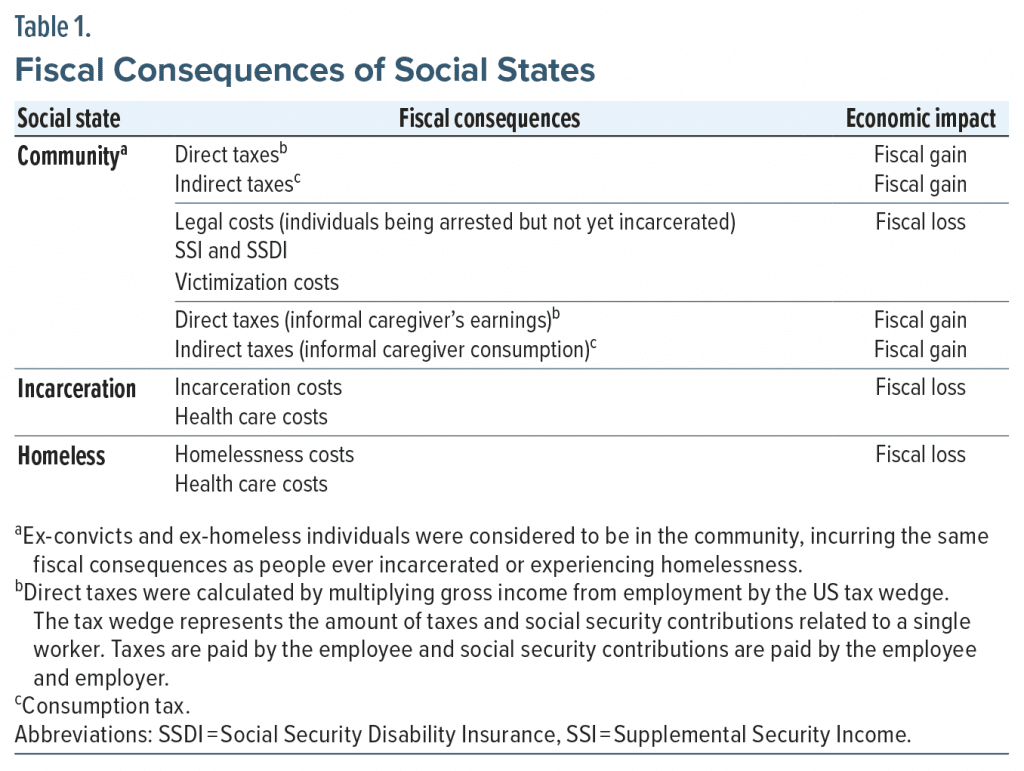

The likelihood of being in a social state was linked to fiscal consequences (taxes revenue and government expenses). The focus of this analysis was to estimate the fiscal burden of schizophrenia on the US Government and SSA, therefore the economic impact of the disease on private institutions was disaggregated from public costs. Foregone employment earnings in PLWS and their informal caregivers compared to the general US population do not constitute a loss to the government but were used to calculate disease-related decrements to labor-related tax contributions and consumption tax, as these affect fiscal revenue. Fiscal consequences with a negative economic impact on the US government (financial support, health care costs, legal costs) were represented as negative values. Sources of government revenue (direct and indirect taxation) were shown as positive values. Fiscal cost and cost consequences were sourced from peer reviewed or national US data and inflated to 2021 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index.12 Fiscal consequences associated to each social state are listed in Table 1. Additional information about the implementation and value of the modeled economic consequences can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Model Results

The results of the model were synthesized as incremental net consequences (INC) calculated as the difference between each cohort’s net present value (NPV). The NPVs for the general population and the schizophrenia cohort were derived using the equations below.23

Taxt = Direct taxt + Indirect taxt + Social security contributionst

Costst = Healtht + Disabilityt + Criminalt + Other transferst

Where i is the cohort under study, r is the discount rate and t is time. Lifetime employment earnings were reported along with the main results of the analysis but were not directly included in the NPV calculations. Earnings were utilized to calculate tax and Social Security contributions per capita.

Since the fiscal burden of disease may also have wider societal implications, we have estimated the societal deadweight loss from schizophrenia. In a perfectly competitive market, without tax-related distortions, transfers from governments to individuals are not counted as societal losses, comprising a redistribution of wealth. Nonetheless, increased public expenditure caused by a burdensome disease, leads to increased taxation which, in turn, affects commodity prices and hence all individuals in a society.42,43 Depending on how progressive the imposed tax rate is, increased commodity prices implies that consumers demand less quantities, leading to a loss of consumer welfare and utility, ie, the societal deadweight loss of increased taxation.44 This was estimated by multiplying the INC estimated by this study by the rate of excess burden reported in the guidelines for the cost-benefit analysis of federal programs (25%).45,46

Sensitivity Analysis

We implemented 5 scenarios to explore assumptions to base case inputs. In these scenarios we varied the US prevalence of schizophrenia, the prevalence of schizophrenia in prisons, the proportion of PLWS using publicly funded health insurance, the source of criminal justice costs and the time horizon of the analysis. One-way sensitivity analyses (OWSA) were conducted by individually replacing most model inputs by the lower or upper bounds of their 95% confidence intervals, to determine which parameters impacted results the most. The results of the OWSA were synthesized in a tornado diagram.

Ethics Approval

The analysis described here is based on secondary data from public sources. No intervention was directly assessed in this work and no individual patient data have been used in the conduct of this evaluation; therefore, no ethics approval is required.

RESULTS

The reported results are per capita and discounted at a 3.0% annual rate. The model predicted that over a lifetime horizon, the schizophrenia cohort would be associated with 26.54 discounted life years compared to 26.96 in their general population equivalents, a 0.42 life years difference. For caregivers and their equivalents, the model estimated an average of 20.84 life years.

Table 2 depicts the incremental fiscal results using base case assumptions. Since the onset of the disease at age 23, a PLWS was associated with an excess fiscal burden of $1,487,243 to the US government and SSA. The largest share of this value was related to health care costs, 42.4% ($630,962), followed by disability benefits, criminal justice, incarceration, victimization, and homelessness costs (39.9%, $593,495), and the remaining 17.7% ($262,786) being due to lost tax revenue. The model also predicted that 1.2% ($17,799) of the incremental net consequences (INC) related to foregone tax revenue from informal caregivers. Overall, the fiscal loss added to $1,505,042 per person over the time horizon of the analysis, which equates to $56,707 per life year lived with schizophrenia.

From a societal perspective, a PLWS was associated with $825,270 foregone earnings from employment, compared to a similar person without the disease. This value was $52,996 in informal caregivers who had to reduce or stop employment. When combined, the fiscal and productivity losses added to $2,383,308 over a lifetime or $89,798 per life year lived with schizophrenia.

Considering the 2021 adult US population (258,327,312) and a 1.19% schizophrenia prevalence28 we can infer that there are currently just over 3.07 million individuals living with the condition. Using our predicted value of $56.7 K per life year lived with schizophrenia we estimate that the fiscal cost to the US government and SSA would result in $173.6 billion lost annually. To society, the estimated economic loss, inclusive of productivity losses would correspond to $271.9 billion annually.

The INC of schizophrenia represents the economic burden of the disease to the US government due to loss productivity and increased need for social benefits. Raising taxes to offset this economic loss could result in friction in the supply and demand equilibrium, leading to an inefficient use of resources and loss of consumer utility. Schizophrenia-related societal deadweight loss from taxation was estimated to be up to $376,262 over the lifetime of a person with the condition or $43.4 billion annually if the entire schizophrenia population was considered.

Scenario Analyses

The incremental fiscal consequences resulting from scenario analyses are shown in Table 3. According to Khaykin et al,47 most of the schizophrenia population are likely recipients of publicly funded health insurance. Assuming that this would be true for all PLWS resulted in an INC of –$1,643,519 per person over their lifetime, a 9.2% increase from base case. Due to the uncertainty around schizophrenia prevalence, we have varied the base case prevalence in the general population from 1.19%28 to 1.62%48 and in incarcerated people from 3.4% in prisons and jails16 to 3.8% in prisons and 5.9% in jails.49,50 The first scenario caused virtually no change to the INC, and the second increased the overall fiscal loss by 1.5% only. We also varied criminal justice cost per arrest (increased from $2,91051 to $3,81752) as there is likely to be variation nationally. The effect of this scenario was negligible, affecting the INC by less than 1%. Finally, we varied the time horizon of the analysis to 35 years since onset of schizophrenia to the age of retirement (rather than death). The INC became $1,299,276, a reduction of 13.7% from baseline.

One-Way Sensitivity Analysis

The effect of the 15 most influential parameters is shown in Figure 2. Direct medical costs in PLWS with no criminal involvement caused the largest change, resulting in a 12.8% increase ($1,698,011) and 10.6% reduction ($1,346,103) of the total fiscal loss. Inputs related to incarceration costs, prevalence of schizophrenia in prisons and among homeless people, and homelessness costs, lead to an approximate 10% increase or decrease of the overall fiscal loss. The remaining parameters led to a less than 7.5% INC variation.

DISCUSSION

We predicted that PLWS would be associated with a lifetime incremental fiscal loss of $1,505,042 compared to an equivalent person unaffected by the disease. Of these costs, 41.9% were related to health care expenses; 39.4% to government transfers in areas such as legal, criminal justice, and social support to homeless or disabled individuals; 17.5% related to forgone tax revenue; and 1.2% to informal care costs. The predicted impact on one’s ability to remain in employment resulted in $825,270 in lifetime foregone earnings. Overall, schizophrenia was predicted to impose an annual fiscal burden of $173.6 billion to the US government. From a societal perspective, losses accrued to $271.9 billion annually, and $315.3 billion if considering deadweight losses from taxation.

We have shown that the economic burden of schizophrenia far exceeds direct medical costs, which are often the focus of policy and cost-effectiveness assessments. Schizophrenia’s direct nonmedical and indirect costs directly increase public expenses, which impact prices and purchasing power and have a real effect on societal welfare capacity.54,55 Consequently, investing in programs and interventions mitigating the burden of schizophrenia will ultimately impact the broader economy. Assessing the value of these interventions should consider the full spectrum of economic consequences generated from schizophrenia and other chronic conditions.

We believe this is the first study estimating the burden of schizophrenia falling on the US government, thus filling an important evidence gap. Our approach differs from other burden of schizophrenia studies21,22 because we modeled the life course of the disease, accounting for the age-specific likelihood of events such as employment, incarceration and homelessness, and age-specific cost-consequences. Additionally, when estimating the impact of informal care, we attempted to predict the effect of caregiving intensity on decreased labor participation. This approach is substantially different from simply calculating replacement costs given weekly hours of informal care. Comparing our results with those from other publications must be done with caution, being mindful of methodological differences.

An additional finding of this study was that despite the higher proportion of PLWS entitled to disability benefits (6.7% vs 2.9%), the overall value of received benefits was lower than that obtained by the population unaffected by schizophrenia. This may be explained by schizophrenia-related mortality, the lack of a formal diagnosis, challenges in navigating the application system, and subsequent dropout.56

Our results were robust to sensitivity analyses, requiring extreme parameter variations to produce meaningful changes to the results. Interestingly, varying the time horizon to 35 years (a more than 50% reduction of the analysis time horizon) led to a 13.8% reduction of the fiscal loss. This finding is important, suggesting that 86.2% of the economic consequences of the disease occur within 35 years of symptom onset.

There are limitations to our analysis. The model uses data from very different sources, involving several assumptions, which consequently increases uncertainty. Inputs such as schizophrenia prevalence in the general population and among the homeless or incarcerated populations are not consensual,16,19,22,48 also contributing to overall uncertainty. Evidence linking symptom remission and relapse to functional and socioeconomic consequences is scarce, with existing sources having limited generalizability to the entire schizophrenia population. Additionally, we have not modeled the effect of incarceration/homelessness on mortality to avoid double-counting and further assumptions. Due to the increased risk of death in incarcerated/homelessness individuals17,57,58 and higher propensity for PLWS to be incarcerated/homeless, this approach is likely to be conservative and underestimate the disease burden. Accounting for costs such as those related to housing, provision of various social services by state departments, and the impact of informal care on caregiver’s health59 would likely contribute to augmenting the estimates of the fiscal economic burden of schizophrenia. Finally, informal caregivers’ health is likely to be impacted by the caregiving process.

CONCLUSION

We estimated the lifetime economic burden of schizophrenia to the US government. This was achieved using a public economic framework linking schizophrenia’s natural history and active disease prevalence to foregone tax contributions in PLWS and informal caregivers, increased government transfers due to disability, criminal justice involvement, homelessness, and public health care insurance utilization, compared to the general US population. The economic impact of schizophrenia far exceeds the costs of health care and should be considered by policymakers defining the level of social support and treatments available to this high-risk population.

Article Information

Published Online: August 9, 2023. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.22m14746

© 2023 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: November 28, 2022; accepted May 5, 2023.

To Cite: Martins R, Kadakia A, Williams R, et al. The lifetime burden of schizophrenia as estimated by a government-centric fiscal analytic framework. J Clin Psychiatry. 2023;84(5):22m14746.

Author Affiliations: Health Economics, Global Market Access Solutions Sarl, St-Prex, Switzerland (Martins, Connolly); Unit of Pharmacoepidemiology & Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Pharmacy, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands (Martins, Connolly); Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Marlborough, Massachusetts (Kadakia, Williams, Milanovic).

Corresponding Author: Mark P. Connolly, MS, PhD, Global Market Access Solutions LLC, 105 Harwick Ct, Mooresville, NC 28117 ([email protected]; [email protected]).

Author Contributions: Drs Martins, Kadakia, and Connolly contributed to collecting the data, developing or reviewing the model, drafting and reviewing the manuscript. All authors were responsible for concept design of the study, drafting of the manuscript, critically reviewing the manuscript, and approving the final content to which they take responsibility for all content.

Relevant Financial Relationships: Drs Martins and Connolly are employees for Global Market Access Solutions and were paid consultants to Sunovion; they hold no financial interest in the sponsoring company. Dr Milanovic is an employee of Sunovion, the sponsoring company. At the time of writing, Drs Kadakia and Williams were employees of Sunovion.

Funding/Support: This work was funded by Sunovion.

Role of the Funders/Sponsors: Sunovion had the opportunity to review and comment on the manuscript, but the authors kept full editorial control over its content. All authors provided final approval on the content of the manuscript.

Clinical Trial Statement: The work described here is based on economic modeling of previously published data. No subjects were recruited for this modeling study, and no individual patient data are included in this publication.

ORCID: Rui Martins: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4200-3106; Mark P. Connolly: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1886-745X

Supplementary Material: Available at Psychiatrist.com.

Clinical Points

- Schizophrenia is a serious and lifelong condition linked to substantial costs to the US government that are worth estimating to inform policy and practice.

- Active disease increases the risk of criminal offense, imprisonment, homelessness, and need for health care, all translating into additional public expenses.

- Treatments and programs effectively maintaining stable disease, particularly in early life, can offset government costs and ultimately alleviate public tax burden.

References (59)

- Tandon R, Gaebel W, Barch DM, et al. Definition and description of schizophrenia in the DSM-5. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(1):3–10. PubMed CrossRef

- American Psychiatric Association. What is schizophrenia? August 2020. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/schizophrenia/what-is-schizophrenia#:~:text=Schizophrenia%20is%20a%20chronic%20brain,thinking%20and%20lack%20of%20motivation.

- Kozma C, Dirani R, Canuso C, et al. Change in employment status over 52 weeks in patients with schizophrenia: an observational study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(2):327–333. PubMed CrossRef

- Goghari VM, Harrow M, Grossman LS, et al. A 20-year multi-follow-up of hallucinations in schizophrenia, other psychotic, and mood disorders. Psychol Med. 2013;43(6):1151–1160. PubMed CrossRef

- Ventura J, Subotnik KL, Gitlin MJ, et al. Negative symptoms and functioning during the first year after a recent onset of schizophrenia and 8 years later. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(2-3):407–413. PubMed CrossRef

- Luciano A, Bond GR, Drake RE. Does employment alter the course and outcome of schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses? a systematic review of longitudinal research. Schizophr Res. 2014;159(2-3):312–321. PubMed CrossRef

- Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, et al. Global epidemiology and burden of schizophrenia: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study 2016. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1195–1203. PubMed CrossRef

- Salomon JA, Haagsma JA, Davis A, et al. Disability weights for the Global Burden of Disease 2013 study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(11):e712–e723. PubMed CrossRef

- Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):85–94. PubMed CrossRef

- Jin H, Mosweu I. The societal cost of schizophrenia: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(1):25–42. PubMed CrossRef

- US Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population for selected age groups by sex for the United States: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2021. 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-national-detail.html

- US Bureau of Economic Analysis. Price Indexes for Personal Consumption Expenditures by Major Type of Product [Table 2.3.4.]. 2022. https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=19&step=2#reqid=19&step=2&isuri=1&1921=survey

- Chong HY, Teoh SL, Wu DB-C, et al. Global economic burden of schizophrenia: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:357–373. PubMed

- Jin H, Tappenden P, Robinson S, et al. A systematic review of economic models across the entire schizophrenia pathway. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(6):537–555. PubMed CrossRef

- Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, et al. Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(1):103–109. PubMed CrossRef

- Prins SJ. Prevalence of mental illnesses in US State prisons: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(7):862–872. PubMed CrossRef

- Wildeman C, Wang EA. Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1464–1474. PubMed CrossRef

- Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Jail incarceration, homelessness, and mental health: a national study. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(2):170–177. PubMed CrossRef

- US Department of Housing and Urban Development. The 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. US Dept of Housing and Urban Development website. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2020-AHAR-Part-1.pdf. 2020.

- Western B, Davis J, Ganter F, et al. The cumulative risk of jail incarceration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(16):e2023429118. PubMed CrossRef

- Cloutier M, Aigbogun MS, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2013. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):764–771. PubMed CrossRef

- Schizophrenia & Psychosis Action Alliance. Societal costs of schizophrenia & related disorders. 2021. https://sczaction.org/insight-initiative/societal-costs/report

- Connolly MP, Kotsopoulos N, Postma MJ, et al. The fiscal consequences attributed to changes in morbidity and mortality linked to investments in health care: a government perspective analytic framework. Value Health. 2017;20(2):273–277. PubMed CrossRef

- Kotsopoulos N, Connolly MP. Is the gap between micro- and macroeconomic assessments in health care well understood? the case of vaccination and potential remedies. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2014;2(1):23897. PubMed CrossRef

- Haynes VS, Zhu B, Stauffer VL, et al. Long-term healthcare costs and functional outcomes associated with lack of remission in schizophrenia: a post-hoc analysis of a prospective observational study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):222. PubMed CrossRef

- Nasrallah HA, Lasser R. Improving patient outcomes in schizophrenia: achieving remission. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(suppl):57–61. PubMed CrossRef

- US Census Bureau. Intercensal Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex and Age for the United States: April 1, 2000, to July 1, 2010 (Table 1). 2011. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/intercensal-2000-2010-national.html

- McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, et al. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30(1):67–76. PubMed CrossRef

- Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362–372. PubMed CrossRef

- Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Correll CU, et al. Psychopharmacological treatment in the RAISE-ETP Study: outcomes of a manual and computer decision support system based intervention. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):169–179. PubMed CrossRef

- Park T, Kuntz KM. Cost-effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia. Value Health. 2014;17(4):310–319. PubMed CrossRef

- Kotov R, Fochtmann L, Li K, et al. Declining clinical course of psychotic disorders over the two decades following first hospitalization: evidence from the Suffolk County Mental Health Project. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(11):1064–1074. PubMed CrossRef

- Minter M. Physician Survey Indicates Need for Novel Antipsychotics. William Blair; 2021.

- Fuller DA. Research Weekly: 2016 Prevalence of Treated and Untreated Severe Mental Illness by State. Treatment Advocacy Centre. 2017. https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/fixing-the-system/features-and-news/3828-research-weekly-2016-prevalence-of-treated-and-untreated-severe-mental-illness-by-state

- Bareis N, Olfson M, Wall M, et al. Variation in psychotropic medication prescription for adults with schizophrenia in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(5):492–500. PubMed CrossRef

- O’Day K, Rajagopalan K, Meyer K, et al. Long-term cost-effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of adults with schizophrenia in the US. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:459–470. PubMed CrossRef

- Schneider-Thoma J, Chalkou K, Dörries C, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral and long-acting injectable antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of adults with schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10327):824–836. PubMed CrossRef

- Arias E, Xu J. United States Life Tables, 2018: US Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr69/nvsr69-12-508.pdf. 2020.

- Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(3):212–217. PubMed CrossRef

- Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical endpoint. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl):17–25. PubMed CrossRef

- Briggs AH, Claxton K, Sculpher MJ. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(9):839. CrossRef

- Browning EK. The marginal cost of public funds. J Polit Econ. 1976;84(2):283–298. CrossRef

- Stuart C. Welfare costs per dollar of additional tax revenue in the United States. Am Econ Rev. 1984;74(3):352–362.

- Mankiw NG. Principles of Economics. 9th ed. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning; 2019.

- New Zealand Treasury. Guide to Social Cost Benefit Analysis. NZ Treasury website. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2015-07/cba-guide-jul15.pdf. 2015.

- US Office of Management and Budget. Circular A-94: Guidelines and Discount Rates for Benefit-Cost Analysis of Federal Programs. wbdg.org website. https://www.wbdg.org/FFC/FED/OMB/OMB-Circular-A94.pdf. 1992. Updated 2022.

- Khaykin E, Eaton WW, Ford DE, et al. Health insurance coverage among persons with schizophrenia in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(8):830–834. PubMed CrossRef

- Mojtabai R. Estimating the prevalence of schizophrenia in the United States using the multiplier method. Schizophr Res. 2021;230:48–49. PubMed CrossRef

- Bronson J, Berzofsky M. Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011–12. Office of Justice Programs website. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/imhprpji1112.pdf. 2017.

- Perälä J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):19–28. PubMed CrossRef

- Swanson JW, Frisman LK, Robertson AG, et al. Costs of criminal justice involvement among persons with serious mental illness in connecticut. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(7):630–637. PubMed CrossRef

- Lin I, Muser E, Munsell M, et al. Economic impact of psychiatric relapse and recidivism among adults with schizophrenia recently released from incarceration: a Markov model analysis. J Med Econ. 2015;18(3):219–229. PubMed CrossRef

- Ascher-Svanum H, Nyhuis AW, Faries DE, et al. Involvement in the US criminal justice system and cost implications for persons treated for schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):11. PubMed CrossRef

- Mankiw G. Application: The Costs of Taxation. Principles Of Economics. 9th ed. Boston: Cengage; 2021:151–166.

- Nakamura Y, Mahlich J. Productivity and deadweight losses due to relapses of schizophrenia in Japan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1341–1348. PubMed CrossRef

- Harvey PD, Heaton RK, Carpenter WT Jr, et al. Functional impairment in people with schizophrenia: focus on employability and eligibility for disability compensation. Schizophr Res. 2012;140(1–3):1–8. PubMed CrossRef

- Daza S, Palloni A, Jones J. The consequences of incarceration for mortality in the United States. Demography. 2020;57(2):577–598. PubMed CrossRef

- Ayano G, Tesfaw G, Shumet S. The prevalence of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders among homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):370. PubMed CrossRef

- Gupta S, Isherwood G, Jones K, et al. Assessing health status in informal schizophrenia caregivers compared with health status in non-caregivers and caregivers of other conditions. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):162. PubMed CrossRef

Save

Cite

Advertisement

GAM ID: sidebar-top