Abstract

Objective: Major depressive disorder (MDD) is common, but current treatment options have significant limitations in terms of access and efficacy. This study examined the effectiveness of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) for the acute treatment of MDD.

Methods: We performed a triple-blind, fully remote, randomized controlled trial comparing tACS with sham treatment. Adults aged 21–65 years meeting DSM 5 criteria for MDD and having a score on the Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II), between 20 and 63 were eligible to participate. Participants utilized tACS or sham treatment for two 20-minute treatment sessions daily for 4 weeks. The primary outcome was change in BDI-II score from baseline to the week 2 time point in an intent-to treat analysis, followed by analyses of treatment-adherent participants. Secondary analyses examined change at the week 1 and 4 time points, responder rates, subgroup analyses, other self-report mood measures, and safety. The study was conducted from April to October 2022.

Results: A total of 255 participants were randomized to active or sham treatment. Improvement in intent-to-treat analysis was not statistically significant at week 2 (P= .056), but there were significant effects in participants with high adherence (P= .005). Significantly greater improvement at week 1 (P= .020) and greater response at week 4 (P= .028) occurred following tACS. Improvements were significantly larger for female participants. There were no significant effects on secondary mood measures. Side effects were minimal and mild.

Conclusions: Rapid, clinically significant improvement in depression in adults with MDD was associated with tACS, particularly for women. Compared to other depression therapies, tACS has 3 key advantages: rapid, clinically significant treatment effect, the ability of patients to use the treatment on their own at home, and the rarity and low impact of adverse events.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05384041

J Clin Psychiatry 2024;85(2):23m15078

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the second leading cause of disability in the United States1 and 11th worldwide.2 Moreover, the rate of clinical depression among US adults more than tripled during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 The prevalence of MDD is also approximately twice as high for females compared to males.4

Inadequate access to depression treatment has been recognized as a public health issue, and the majority of patients treated with psychotropic medications receive their prescriptions from their primary care physician, rather than a psychiatrist.5 It has been argued that depression is significantly undertreated, particularly in primary care settings.6 Importantly, initial improvements in mood typically occur only after 2–4 weeks of treatment with medications and 4–8 weeks with psychotherapy.7 Delayed responses to treatment can result in diminished adherence.8 Controlled substances, such as esketamine, are fast-acting but are associated with substantial side effects.9 There is a need for depression treatments that pose low risk to patients and provide rapid benefit.

Noninvasive brain stimulation (NIBS) is a collection of techniques that stimulate or alter brain activity from outside of the body that includes clinic-based treatments such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and electroconvulsive therapy.10 Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) is a form of wearable brain stimulation that delivers a low-intensity, pulsed, alternating current via scalp electrodes so that current passes through the skull to modulate neural activity.11,12 The current in tACS is often sinusoidal although a range of waveforms is possible.13 This is in contrast to transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which delivers a constant current throughout the treatment period. The Food and Drug Administration regulates tACS within the category of cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES), which includes tACS and tDCS devices intended to treat depression, anxiety, or insomnia.14 An extensive evidence-based synthesis concluded that tACS may have benefit for depression without serious side effects, although the overall quality of the evidence was low.15 One recent randomized trial found that active tACS treatment was associated with higher remission rates compared to sham treatment.16 There is a critical need for further controlled research to investigate the efficacy of tACS for the treatment of depression.

The goal of this study was to provide more conclusive evidence by conducting a large-scale, randomized controlled clinical trial in individuals with current MDD. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the trial was conducted remotely. The primary objective was to test the safety and effectiveness of tACS, compared to sham treatment, for the treatment of MDD in adults.

METHODS

Study Design

A triple-blind, fully remote, randomized controlled trial was conducted in the United States. Subjects were randomly assigned (approximately 1:1) to active or sham treatment. The subjects, assessors, and sponsor were all blinded to study conditions. The James Blinding Index was used to assess the success of subject blinding.

The study was performed in compliance with good clinical practice. The study protocol was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05384041) and was fully approved by an institutional review board. The study was conducted from April to October 2022.

Patients

Adults meeting the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), criteria for MDD, diagnosed by a study clinician, of moderate-severe severity on the Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II), could participate. Eligibility criteria were as follows: age 21–65 years; US resident; able to read/write English; able to commit to the treatment protocol; no history of suicide attempt or active suicidal ideation with plan or intent in the past 30 days; no previous hospitalization for mental health condition within 1 year; no use of neuromodulation within 1 year; no changes in prescription nervous system medication within 30 days; no use of recreational substances, hypnotics, steroids, and/or marijuana products within 30 days; not experiencing problems with alcohol or substance abuse in the past 12 months; not experiencing mental health disorders other than MDD; no known history of heart disease or trigeminal neuralgia; and no pacemaker or any form of medical electronics. Sexually active females of childbearing potential were required to commit to practicing at least 1 method of contraception during the study.

Procedures

All data were entered into the Climb electronic patient-reported outcomes clinical trials software platform. Potential subjects completed an online prescreening process. Eligible participants met virtually with investigative staff, who reviewed the trial’s purpose, procedures, risks and benefits, compensation, and data confidentiality. Interested participants then completed the informed consent form electronically via DocuSign. Participants began a 14-day lead-in period, after which they retook the self-report assessments and a computer administered Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A BDI-II score between 20 and 63 was required at both initial prescreening and baseline to participate. The goal of this lead-in was to eliminate participants with transient depression that could potentially bias study outcomes. Given the timing of these assessments, participants had to have been experiencing depression for at least 1 month prior to the start of the treatment. During a clinical interview with a study clinician, participants were assessed using the DSM-5 criteria for MDD and other psychiatric disorders, and MINI responses were reviewed for final determination of eligibility.

Eligible participants were randomized to either the active treatment group (active device) or the control group (sham device) by an unblinded investigative staff member, who had no participant contact and did not discuss group allocation with other members of the investigative team. The randomization assignments were made sequentially. There were no restrictions or other inputs dictating randomization order for the initial 250 randomizations required by the protocol. Excess randomizations beyond 250 used a table with equal allocations between active and sham arms in every block of 10.

tACS Treatment

This study investigated the Fisher Wallace Stimulator, Model FW-200 tACS device. The FW-200 is a wearable, self-administered tACS device powered by 2 AA batteries and comprised a handheld pulse generator, 2 electrodes that attach to the pulse generator via wires, and an adjustable headband used to secure the electrodes. The FW-200 delivers 2 mA (±10% tolerance) of pulsed alternating current, with a pulse width of 33.3 microseconds, using a rectangular, bipolar (bidirectional) waveform, employing a 15,000-Hz carrier frequency and 2 modulating frequencies of 500 Hz and 15 Hz, delivered through two 1.5-inch-diameter (circular) sponge electrodes moistened with tap water and secured under the headband at the squamous temporal bone above the posterior aspect of the zygomatic arch on either side of the head. The device turns off automatically after each 20-minute treatment session. The sham tACS device appeared to function identically to the active device but did not deliver electrical stimulation. Participants were instructed to engage in quiet activity during each 20- minute treatment session. After the training session, participants were asked which type of investigational device they believed they received (active device or control) and selected from 5 options to indicate the strength of this belief. The participants’ responses were analyzed using the James Blinding Index.17 Participants from both the sham and active treatment arms engaged in 20 minutes of usage twice daily, once after waking for the day and once prior to going to bed. Each day, subjects reported whether they used the study device as instructed and any changes to their health status or medications. After 1, 2, and 4 weeks of treatment, participants completed clinical outcome measures and reported any adverse events (AEs) or changes to concomitant medications.

Outcomes

The assessments used in this trial are commonly used in the mental health field to evaluate psychiatric disorders.7,18

Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition. The BDI-II is a multiple-choice self-report inventory that assesses severity of depression. The BDI-II contains 21 items on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3 for a total score from 0 to 63.19

Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview. The MINI is an assessment tool for the major psychiatric disorders.18 In the current trial, the MINI was used in a participant self-administered format and was confirmed during participants’ telemedicine visit with a clinician in order to rule out any comorbid diagnoses.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a 9-item scale covering the DSM-5 criteria for MDD. Scores range from 0 to 27.20

Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology. The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report (QIDS-SR) is a 16-item rating scale that assesses 9 criterion symptom domains to diagnose a major depressive episode. The total score ranges from 0 to 27.21

Statistical Analysis

Sample size for the study was based on the primary outcome measure of change in the BDI-II. Sample size calculations were based on a planned sample size of 250 evaluable subjects with 1:1 allocation. The trial provided 80% power assuming a population mean difference between groups of 3.2 and a common standard deviation of 9 based on a 2-sided 2-sample Student t test with an alpha of 0.05. Previous data suggested the standard deviation for 2-week improvement to be ∼6.5; however, a conservative estimate of 9 was used for these calculations.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4. The primary end point analysis was performed at the 1-sided 0.025 alpha level, with all other analyses based on a nominal 2-sided 0.05 alpha level. Confidence intervals and P values for secondary end points and subgroup analyses were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. The primary analyses used an intent-to treat (ITT) analysis as a more conservative estimate of treatment effects. Select analyses were then conducted with only subjects who demonstrated high self-reported adherence to twice-daily use each day up to the primary 2-week time point (per-protocol treatment).

The primary efficacy end point was defined as the change in BDI-II score at week 2 compared to baseline in the active treatment vs control arm. Analysis was performed using a linear regression model for change, adjusted for each subject’s baseline value. Missing data for the primary end point only were handled via multiple imputation based on a fully conditional specification with the following covariates: age, sex, baseline BDI-II, week 1 BDI-II, and available follow up BDI. Imputation was performed separately by the treatment group. Several sensitivity analyses were performed. These were supportive in nature and employed nominal confidence levels. The primary end point was repeated using the as-treated and per protocol populations. The same statistical methods as those used by the primary end point were utilized. Secondary analyses were conducted for the week 1 and 4 time points and for the PHQ-9 and QIDS-SR at all time points, adjusting for baseline scores. A secondary analysis compared the BDI-II responder rate at weeks 1, 2, and 4, with response defined as 50% or greater improvement in score from baseline. Subgroup analysis of the primary end point was performed in the ITT analysis set for the subgroups defined by sex, race, and baseline BDI-II [moderate (20–28) vs severe (29–63)] by utilizing an interaction between treatment arm and subgroup. Interaction term with a P value <.15 was further examined per the prespecified analysis plan. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was performed. An exploratory analysis examined whether concurrent use of antidepressant medications affected treatment outcomes.

RESULTS

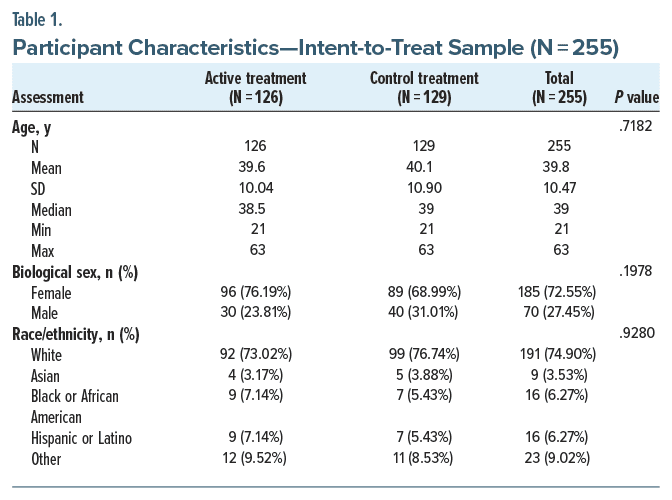

Patient Characteristics

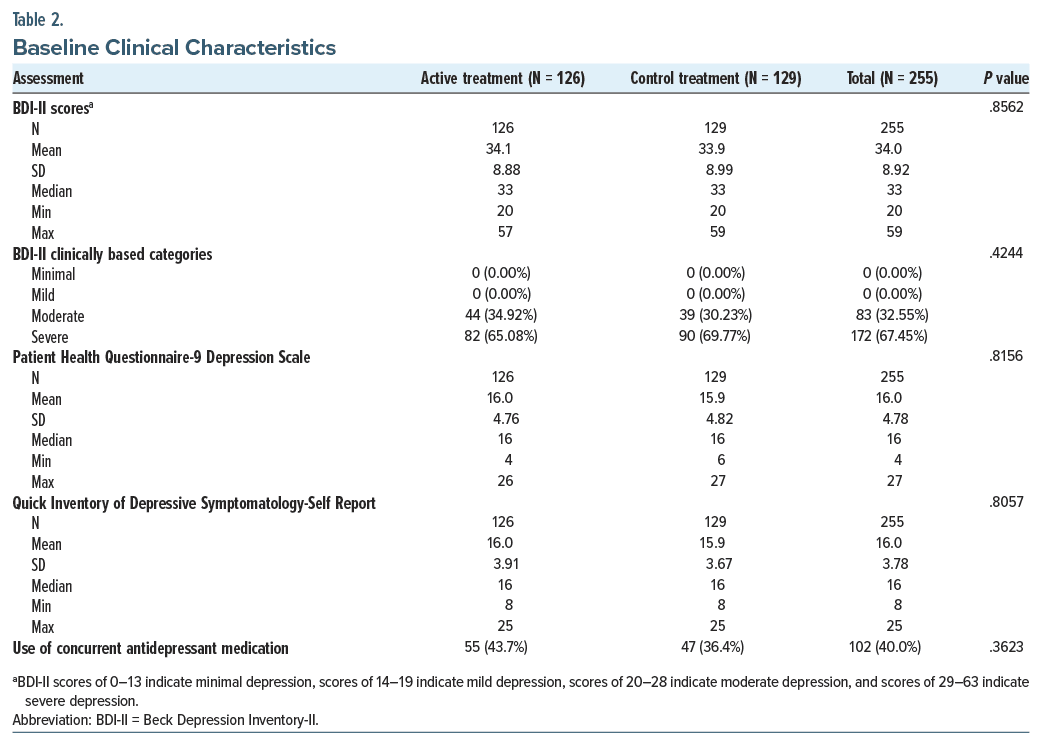

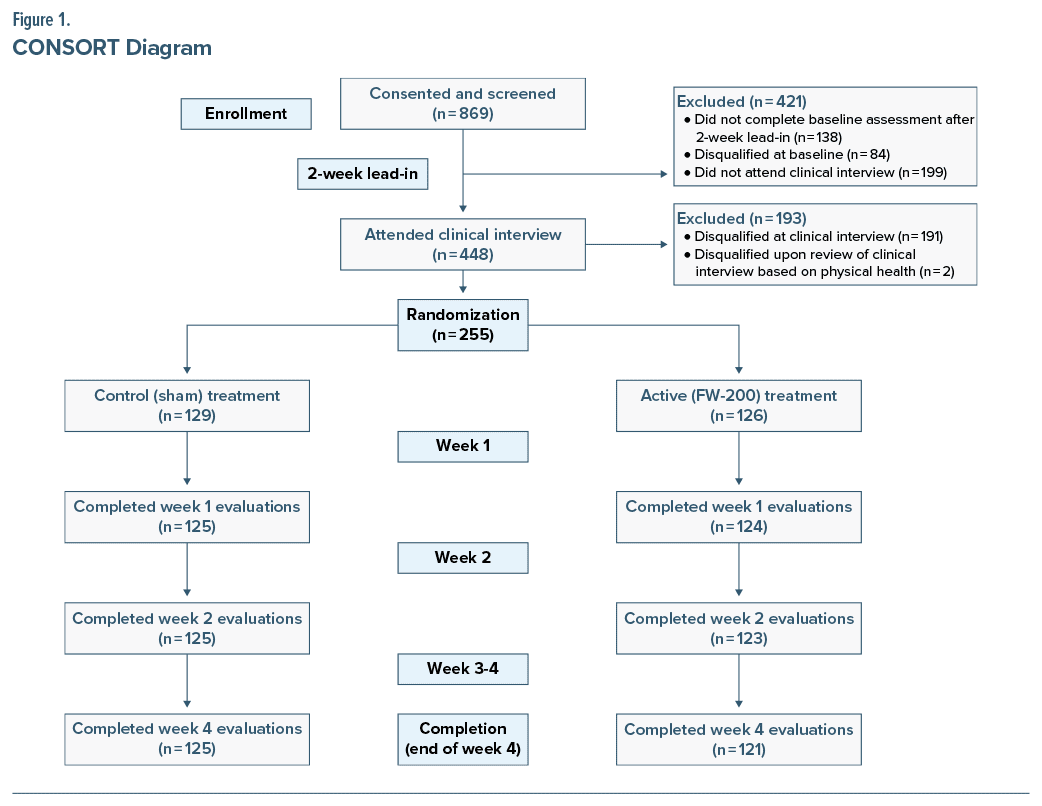

Participants were recruited between April and August 2022. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Based on baseline BDI-II scores, 32.6% and 67.5% of the sample reported moderate and severe depression symptoms, respectively, as shown in Table 2. A CONSORT diagram showing the flow of participants is presented in Figure 1.

The blinding index (0.718, 95% CI, 0.668 to 0.768) showed a lower confidence bound above 0.5 and is considered successful blinding.17 Overall, 56% and 45% in the active and control groups, respectively, did not believe they knew their assigned treatment. Self-reported adherence was high, with 85.1% of participants reporting twice-daily usage throughout the first 14 days. When broken down by group, 86.5% of subjects in the active group engaged in complete use throughout 14 days and 83.7% in the sham group.

Outcome Measures

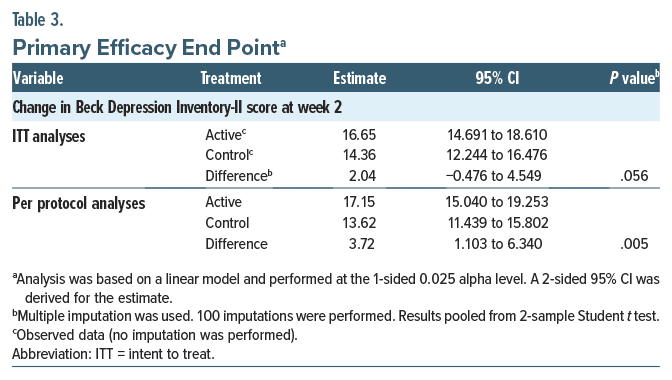

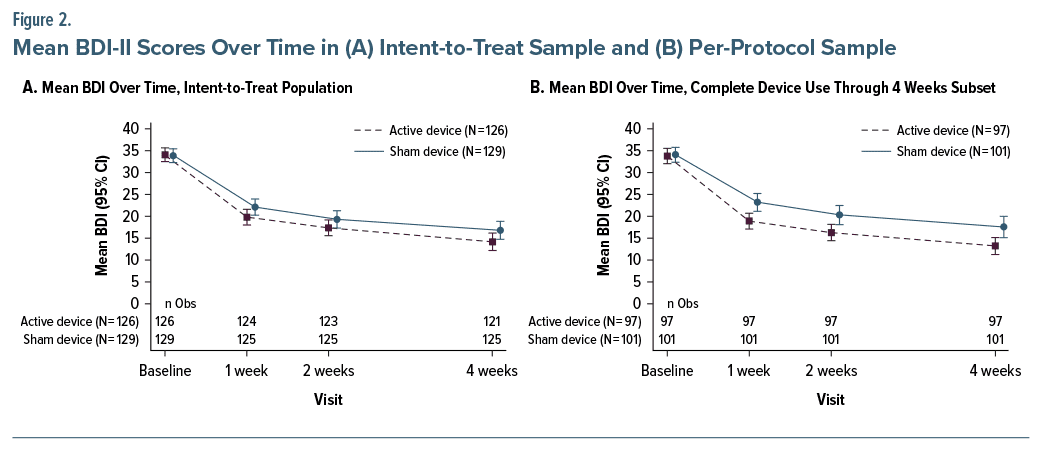

Table 2 presents the baseline statistics for all clinical outcome measures. The results of the primary effectiveness end points related to the change in BDI-II score at 2 weeks for the ITT population are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2A. Both treatment groups showed improvements in mean BDI-II scores at week 2 compared to baseline (active: 16.65; control: 14.36), with the confidence bound for each group excluding zero and lower bound values of 14.69 and 12.24, respectively, for the active and control groups. The difference between groups was not significant (difference: 2.04; 1-sided P = .056, 95% CI, −0.476 to 4.549). Post hoc analysis of participants with 100% compliance in the first 14 days showed a significantly greater BDI-II improvement in the active treatment versus control at 2 weeks (difference: 3.72, P = .005, 95% CI, 1.103 to 6.340) (Figure 2B). There were also significant effects at the secondary 1-week (difference: 3.10, P = .022) and 4-week (difference: 4.10, P = .018) time points (Supplementary Table 2).

In preplanned subgroup analyses, females showed a nominally significant difference between active and control treatments at week 2 on ITT analysis (17.9 vs 14.2, respectively; nominal subgroup P=.020; Supplementary Table 1) and a significant difference on per-protocol analysis (18.3 vs 13.76; nominal subgroup P=.008). There was not a nominally significant difference for males. There was no evidence of interaction of subgroup differences for race or baseline BDI-II severity.

In secondary analyses of BDI-II scores at weeks 1 and 4 compared to baseline, treatment effects favored active treatment at both time points (P = .020 and .028, respectively) (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2). The active treatment group showed a significantly greater change from baseline compared to the control treatment at week 1 (P = .048). Like the BDI-II, scores on the PHQ-9 and QIDS-SR also showed a consistent treatment effect that directionally favored the active treatment at all time points based on point estimates (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). However, there were no statistically significant differences between active and control treatments on these measures. Finally, in responder analyses by week 4, the active treatment group showed a significantly greater responder rate than the control group (65.08% vs 52.71%, P = .045) (Supplementary Table 5). Sex-specific responder analyses revealed that active treatment was associated with significantly higher response at most time points only in females (Supplementary Table 6). Concurrent use of antidepressant medication was fairly common, with 43.7% of the active treatment group and 36.4% of the sham group reporting use (Table 2). Within the active treatment group, there were no differences in outcome at week 2 between those on and off antidepressant medications (P = .543).

Safety Results

The numbers of AEs were small; 19 subjects (15.1%) in the active group reported 34 events and 10 subjects (7.8%) in the control group reported 13 events. No serious AEs were reported. Only 1 AE (skin discomfort) led to device discontinuation. Complete reporting of all AEs is provided in Supplementary Table 7.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the effectiveness of tACS, compared to sham treatment, for MDD of at least moderate severity in adults. In ITT analyses, both the active and control groups exhibited clinically significant improvements in self-reported depression severity at 2 weeks, but the difference in improvement between groups was not statistically significant. Self-reported adherence was high, with 85% of participants reporting twice-daily use every day in the first 2 weeks, and in these participants, the difference between groups was statistically significant at all time points. Treatment effects were greatest among female participants for whom active tACS was superior to sham tACS across time points. There was a statistically significant advantage of active treatment over control at 1 week, and the clinical response rate was significantly greater after 4 weeks for those who received active treatment. Active tACS greatly exceeded the 17.5% threshold of minimal clinically important within-group difference established for the BDI-II.22

Clinical gains were larger for female participants, which is noteworthy, given the higher rates of MDD compared to males.4 Post hoc investigation of randomization revealed an imbalance in sex and severity distribution such that 72.5% of male participants in the control group were severely depressed at baseline, compared to only 50% in the active group. Among female participants, the prevalence of severe depression at baseline was proportional in the active and control groups at 69.8% and 68.5%, respectively. The imbalance in males may have contributed to the weaker effects observed in males.

It is important to consider these findings in the broader context of NIBS for the treatment of MDD. First, there are parallels between the results of this study and a pivotal TMS study.23 Both treatments showed statistical trends at the time point for their primary end point, but tACS also demonstrated a statistically significant benefit over sham treatment at the secondary week 1 time point. It is also useful to compare these effects with studies of other CES approaches, for which the evidence of efficacy is mixed.15 Other devices often utilize electrodes that are not placed directly on the scalp, so the current, while alternating, is not delivered transcranially. The waveform of the current may also be an important parameter, and the rectangular waveform of the FW-200 may provide an advantage over the sinusoidal current produced by other devices. Current delivered in square wave or sawtooth waveforms may be more effective than that delivered in sinusoidal waveforms for entraining neural oscillations.24,25

In contrast to several other forms of NIBS, tACS treatment is patient-led at home and requires no provider involvement following the initial prescription. Other treatments involve regular clinical appointments, imparting a substantially higher patient burden. For many patients, this considerable time commitment may make treatment untenable. Importantly, the demand for mental healthcare far outstrips the supply of available providers, so effective patient-led treatments are needed to address this unmet need.

There are a number of notable strengths of this study. First, a 14-day lead-in period was included to reduce the impact of improvements due to natural remission of MDD. Second, active treatment was compared to the use of a sham treatment without electrical stimulation, providing a more rigorous test of treatment effectiveness compared to a waitlist or treatment-as-usual control condition. The validity of the control condition is supported by analyses indicating successful blinding. Participants were allowed to be on concurrent antidepressant treatment to mimic real-world conditions in which the device would likely be used. Use of antidepressants was not associated with any differences in treatment outcome (results not shown). Finally, rates of treatment adherence were very high, and dropout was very low, with 85.1% of participants indicating that they used the device according to instructions for the first 2 weeks of treatment.

In contrast, a limitation of the study is the reliance on self-reported patient outcome measures, which are subject to more cognitive biases than clinician administered assessments and may have contributed to the high sham response. Self-report was also used for determining adherence, and the reported rates may not accurately reflect actual use patterns. Treatment effects beyond 4 weeks are not known and will need to be tested in future studies. Although the sham treatment condition is a strong comparator, it does not permit assessment of naturalistic changes in mood that might have occurred without any treatment. The large improvements in the sham group also make it difficult to know how much of the treatment effect was due to the direct effects of the tACS device vs placebo effects. Having all subjects engage in 40 minutes per day of calm activities may itself have had therapeutic benefits irrespective of tACS. This study was not designed to detect differences in subpopulations (eg, differing severity levels or in females). Finally, the sample predominantly identified as Caucasian, so future studies need to investigate efficacy in more diverse samples.

In conclusion, tACS treatment can produce rapid, clinically significant improvements in depression in adults with MDD relative to baseline severity of depression, particularly for females. Not surprisingly, effects were largest in those with high rates of adherence, and for these individuals, clinical improvements were significantly higher at all time points. Although it is difficult to tease out the contribution of placebo effects to these improvements, tACS has notable advantages in relation to other antidepressant therapies, including rapid, clinically significant treatment effects, the ability of patients to use the treatment on their own at home, and the rarity and low impact of the AEs. Future studies are needed that examine treatment over longer periods of time to determine whether treatment effects can be maintained.

Article Information

Published Online: April 22, 2024. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.23m15078

© 2024 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: August 24, 2023; accepted December 27, 2023.

To Cite: Gehrman PR, Bartky EJ, Travers C, et al. A fully remote randomized trial of transcranial alternating current stimulation for the acute treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2024;85(2):23m15078.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Gehrman); Bartky HealthCare Center, LLC, Livingston, New Jersey (Bartky); North American Science Associates Inc, St Louis Park, Minnesota (Travers); Affective Care, New York, New York (Lapidus).

Corresponding Author: Philip R. Gehrman, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, 3535 Market St, Suite 670, Philadelphia, PA 19104 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Gehrman has received research support from Merck Inc and has been a paid consultant for Eight Sleep, Eisai Inc, Fisher Wallace Laboratories, and Idorsia. Dr Bartky has received speaker funding from Supernus Pharmaceuticals and was paid to perform clinical assessments by Fisher Wallace Laboratories for precursors to this study. Dr Lapidus has received financial support and has personal or indirect ownership or options interest in Affective Care, Victory Recovery Partners, Journey Clinical, Sol2rise, Psychiatric Care Medical, Anxiety Psychiatry Medical, Woolsey Pharmaceuticals, Cecilia Health, and Enalare and has received research support, nonfinancial support, and fees from BrainsWay Ltd, MAPS, Medtronic, Neuronetics, and Roche, as well as consulting fees from FCB Health, SmartAnalyst, Cipla, Janssen, and LCN Consulting Inc. Dr Lapidus has been a paid consultant for Fisher Wallace Laboratories for this study and 3 other clinical trials. Fisher Wallace contracted with North American Science Associates Inc (NAMSA), for statistical support. Mr Travers reports no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Funding/Support: This study was sponsored by Fisher Wallace Laboratories Inc.

Role of the Sponsor: The study sponsor provided financial support for the study and statistical analysis. They provided feedback on the manuscript, but the final content and conclusions are those of the authors.

Acknowledgments: Chris Mullin, MS (NAMSA), and Britta Rupp, PhD (NAMSA), performed the data analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the study data.

ORCID: Philip Gehrman: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1054-7475

Supplementary Material: Available at Psychiatrist.com.

Clinical Points

- Noninvasive brain stimulation approaches such as transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) have been proposed as treatments for major depressive disorder (MDD), but adequately powered controlled trials are lacking.

- For patients with MDD, tACS produces rapid effects with minimal safety risk.

References (25)

- Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–2223. PubMed CrossRef

- Murray CJL, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591–608. PubMed CrossRef

- Czeisler ME, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic – United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049–1057. PubMed CrossRef

- Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(8):783–822. PubMed CrossRef

- Bishop TF, Ramsay PP, Casalino LP, et al. Care management processes used less often for depression than for other chronic conditions in US primary care practices. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(3):394–400. PubMed CrossRef

- Price L, Briley J, Haltiwanger S, et al. A meta-analysis of cranial electrotherapy stimulation in the treatment of depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;135:119–134. PubMed CrossRef

- Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

- Martin-Vazquez MJ. Adherence to antidepressants: a review of the literature. Neuropsychiatry (London). 2016;6(5):236–241. CrossRef

- Popova V, Daly EJ, Trivedi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of flexibly dosed esketamine nasal spray combined with a newly initiated oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized double-blind active-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):428–438. PubMed CrossRef

- Albizu A, Indahlastari A, Woods AJ. Non-invasive brain stimulation. In: Gu D, Dupre ME, eds. Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging. Springer Nature; 2019. CrossRef

- Thut G, Schyns PG, Gross J. Entrainment of perceptually relevant brain oscillations by non-invasive rhythmic stimulation of the human brain. Front Psychol. 2011;2:170. PubMed CrossRef

- Zaehle T, Rach S, Herrmann CS. Transcranial alternating current stimulation enhances individual alpha activity in human EEG. PLoS One. 2010;5(11): e13766. PubMed CrossRef

- Antal A, Paulus W. Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:317. PubMed CrossRef

- Food and Drug Administration. Neurological devices; reclassification of cranial electrotherapy stimulator devices intended to treat anxiety and/or insomnia; effective date of requirement for premarket approval for cranial electrotherapy stimulator devices intended to treat depression. Fed Regist. 2019;84(245): 70003–70013.

- Shekelle PG, Cook IA, Miake-Lye IM, et al. Benefits and harms of cranial electrical stimulation for chronic painful conditions, depression, anxiety, and insomnia: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(6):414–421. PubMed CrossRef

- Wang H, Wang K, Xue Q, et al. Transcranial alternating current stimulation for treating depression: a randomized controlled trial. Brain. 2022;145(1): 83–91. PubMed

- Kolahi J, Bang H, Park J. Towards a proposal for assessment of blinding success in clinical trials: up-to-date review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37(6): 477–484. PubMed CrossRef

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–33;quiz 34–57. PubMed

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation; 1996.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J General Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. PubMed CrossRef

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–583. PubMed CrossRef

- Button KS, Kounali D, Thomas L, et al. Minimal clinically important difference on the Beck Depression Inventory–II according to the patient’s perspective. Psychol Med. 2015;45(15):3269–3279. PubMed CrossRef

- O’Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(11):1208–1216. PubMed

- Fröhlich F, McCormick DA. Endogenous electric fields may guide neocortical network activity. Neuron. 2010;67(1):129–143. PubMed

- Dowsett J, Herrmann CS. Transcranial alternating current stimulation with sawtooth waves: simultaneous stimulation and EEG recording. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:135. PubMed CrossRef

This PDF is free for all visitors!

Save

Cite