Because this piece does not have an abstract, we have provided for your benefit the first 3 sentences of the full text.

Robert L. Spitzer, MD, died of heart disease on December 25, 2015. Bob was one of the best-known psychiatrists in America and had a lasting impact on psychiatric diagnosis and nosology.

Dr Spitzer spent his entire academic career at Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute (PI) and is best known for his work in developing DSM-III, which shifted the diagnostic paradigm in American Psychiatry.

This work may not be copied, distributed, displayed, published, reproduced, transmitted, modified, posted, sold, licensed, or used for commercial purposes. By downloading this file, you are agreeing to the publisher’s Terms & Conditions.

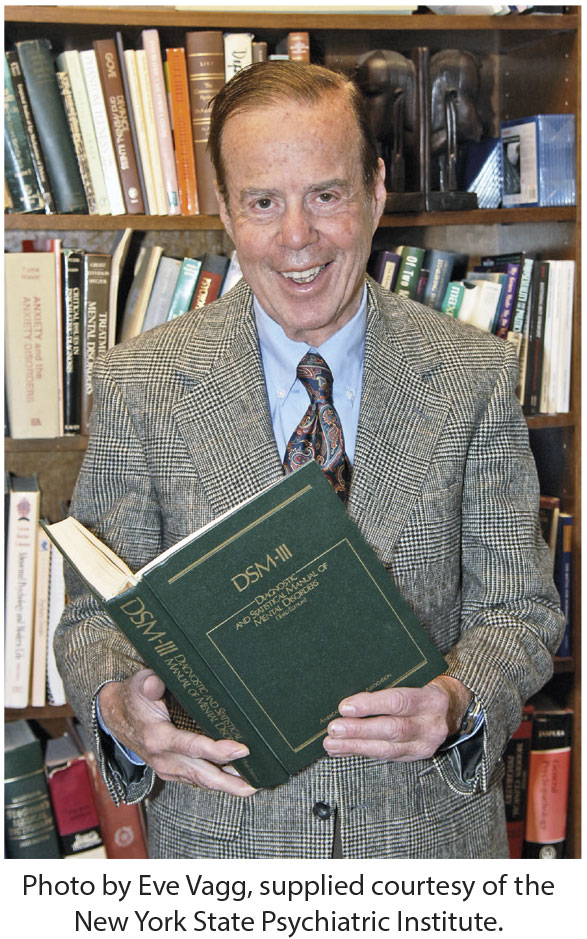

Robert L. Spitzer, MD

1932-2015

Robert L. Spitzer, MD, died of heart disease on December 25, 2015. Bob was one of the best-known psychiatrists in America and had a lasting impact on psychiatric diagnosis and nosology.

Dr Spitzer spent his entire academic career at Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute (PI) and is best known for his work in developing DSM-III, which shifted the diagnostic paradigm in American Psychiatry. To enable the epic transition from DSM-II to DSM-III, Spitzer and colleagues developed a structured psychiatric interview, the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS), which documented a diagnosis based on symptoms and the course of illness. The Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC), a modification of the criteria for diagnosis developed at Washington University in St Louis (the "Feighner Criteria"), were field tested to establish validity and interrater reliability.

I was at PI in the 1970s while the SADS and RDC were being developed. Spitzer asked me to review an early version of the SADS, and I recommended that he test it out among some of the bipolar patients in our Lithium Clinic. This process resulted in useful modifications of the SADS.

Research studies of the RDC evolved into the criteria for diagnosis in DSM-III. Spitzer’s next task was to gain approval from the American Psychiatric Association, and he took on this task with gusto. DSM-III was conceptually at odds with how diagnoses had previously been made. After much discussion, debate, and controversy, DSM-III was adopted by the APA.

Spitzer framed the concept that a disorder should have associated disability, attempting to establish criteria for dividing normal variation from pathology. In a groundbreaking shift, the DSM-III recognized homosexuality as a mental disorder only if there was resulting psychosocial disability. A grand rounds at PI, in which this concept was introduced, pitted Spitzer against many colleagues in the psychoanalytically oriented faculty.

Bob relished the process of bringing science to the discussion of diagnosis. He advocated the use of semistructured diagnostic interviews to improve the historically poor interrater reliability in psychiatry. He was not timid in the discussion of these issues, which flew in the face of common psychiatric practice at that time. Our field should not underestimate the amazing transformation of psychiatry worldwide that evolved from the changes made by DSM-III.

After DSM-III, he continued his research into diagnostic issues, partly in collaboration with his wife, Janet B. W. Williams, PhD. They moved to Seattle, Washington, shortly before his death. My own career was enriched by knowing Bob, and his influence on modern psychiatry is indelible.

This PDF is free for all visitors!

Save

Cite