Despite the availability of effective treatments for MDD, many individuals have difficulty achieving remission. Residual symptoms can be difficult to differentiate from treatment side effects. Through 2 comic-based case presentations, this CME activity depicts common clinical scenarios and provides evidence-based strategies for effectively identifying and managing residual symptoms of MDD.

Find more articles on this and other psychiatry and CNS topics:

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders

CME Background Information

Supported by an educational grant from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Participants may receive credit by reading the activity, correctly answering the posttest question, and completing the evaluation.

Objective

After completing this educational activity, you should be able to:

- Develop a treatment plan for pediatric patients with bipolar depression using current evidence

Financial Disclosure

The faculty for this CME activity and the CME Institute staff were asked to complete a statement regarding all relevant personal and financial relationships between themselves or their spouse/partner and any commercial interest. The CME Institute has resolved any conflicts of interest that were identified. No member of the CME Institute staff reported any relevant personal financial relationships. Faculty financial disclosure is as follows:

Dr DelBello is a consultant for Akili, CMEology, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Neuronetics, Pfizer, Sunovion, Supernus, and Takeda and has received grant/research support from Amarex, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Otsuka, Shire, Sunovion, Supernus, and Lundbeck.

Accreditation Statement

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit Designation

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., designates this enduring material for a maximum of 0.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

The American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) accepts certificates of participation for educational activities certified for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ from organizations accredited by ACCME or a recognized state medical society. Physician assistants may receive a maximum of 0.5 hours of Category I credit for completing this program.

To obtain credit for this activity, study the material and complete the CME Posttest and Evaluation.

Release, Review, and Expiration Dates

This brief report activity was published in December 2018 and is eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ through December 31, 2020. The latest review of this material was December 2018.

Statement of Need and Purpose

Clinicians often base their diagnoses of pediatric bipolar disorder on clinical observations rather than using assessment tools. Both the diagnostic criteria that were written for adults and the frequent overlap of symptoms with other conditions can complicate the diagnostic process. Clinicians are not comfortable with treatment options for pediatric bipolar depression, and few up-to-date guidelines and rigorous clinical trial data in this population are available. Providers are failing to ensure coordination of continuity of care from pediatric to adult facilities. Clinicians need information on the presentation of pediatric patients with bipolar disorder, on the characteristics that distinguish this disorder from other conditions, and on clinical tools to help them conduct a differential diagnosis. Clinicians also need information about the safety and efficacy of treatments that have been investigated in pediatric bipolar depression, the educational needs of patients and their parents, and how to coordinate a smooth transition from pediatric to adult mental health services. This activity was designed to meet the needs of participants in CME activities provided by the CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., who have requested information on pediatric bipolar depression.

Disclosure of Off-Label Usage

Dr DelBello has determined that lamotrigine, lithium, and quetiapine are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of bipolar depression in pediatric patients.

Review Process

The entire faculty of the series discussed the content at a peer-reviewed planning session, the Chair reviewed the activity for accuracy and fair balance, and a member of the External Advisory CME Board who is without conflict of interest reviewed the activity to determine whether the material is evidence-based and objective.

Acknowledgment

This brief report is derived from the planning teleconference series “Overcoming Challenges in Diagnosis and Depression Management in Pediatric Bipolar Disorder,” which was held in June and July 2018 and supported by an educational grant from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The opinions expressed herein are those of the faculty and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the CME provider and publisher or the commercial supporter.

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Ohio

Depression in pediatric patients with bipolar disorder is a severe state that, compared with mania, is more prevalent and persistent and carries a higher risk for mortality.1,2 Yet, research into pediatric mania has far outpaced research into pediatric bipolar depression (PBD); numerous treatments are available for mania, but pharmacologic treatments for bipolar depression in this age group are scarce. Despite this limitation, available evidence supports a multimodal treatment strategy to manage depression in youth with bipolar disorder.1

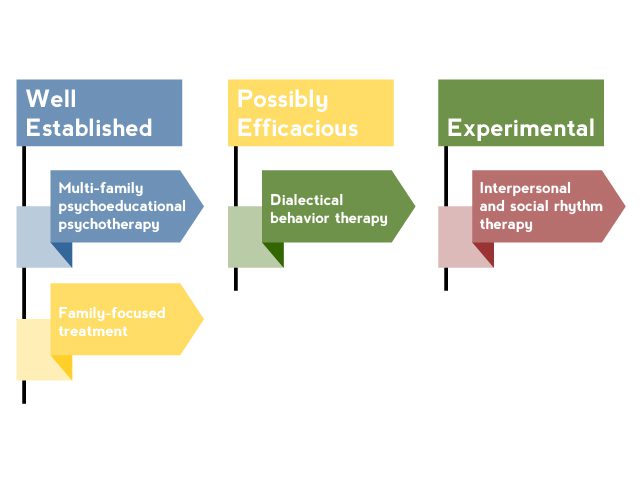

AV 1. Nonpharmacologic Interventions for Pediatric Bipolar Disorder

Based on Goldstein et al3 and Fristad and Macpherson.4

Nonpharmacologic Interventions

Although nonpharmacologic interventions should not be considered as monotherapy, they are a critical component in the treatment of PBD. Adjunctive psychosocial treatment is needed to educate patients and their families about bipolar disorder and important self-monitoring and management strategies.3 Several psychosocial interventions have been studied in pediatric bipolar patients (AV 1). The most effective interventions shared common elements that should be incorporated into the treatment of all patients with PBD.4 These elements include the following:

- Family involvement. When a child has bipolar disorder, the entire family is affected and, therefore, must be involved in treatment. Family dysfunction and conflict are common,5 and high levels of stress and conflict in the home increase a patient’s likelihood of relapse.6

- Psychoeducation. To be informed and active participants in treatment, patients and their families must have a thorough knowledge of bipolar disorder, including symptoms, course, risk and protective factors, and available treatments. Attitudes towards treatment should be assessed to address misconceptions that might lead to nonadherence.

- Skill-building. Several skills can help patients and families manage symptoms and cope with the disorder, thereby reducing conflict, increasing positive interactions, and improving mood. These skills include problem-solving, communication enhancement, and cognitive-behavioral techniques.3,4,6

- Relapse prevention. The coping and problem-solving skills previously mentioned can be indispensable to preventing relapse. In addition, self-management skills such as maintaining a healthy diet and good sleep hygiene; getting regular exercise; avoiding potentially triggering substances such as caffeine, alcohol, or illicit drugs; and adhering to medication are effective relapse prevention skills that can be incorporated into a psychosocial treatment plan.4,7 Mood charting can be extremely helpful, and tools such as cell phone applications can help simplify this task.

Pediatric patients have a particularly pressing need to acquire skills that are included in effective psychosocial treatments. Young patients need self-management skills to be successful as they confront the academic and social challenges of adolescence.7 Furthermore, it is imperative that pediatric patients become adept at these skills before transitioning into adulthood, when they will be required to function more autonomously. For young patients with bipolar disorder who reach the age of 18 years without the ability to cope with their symptoms, the consequences can be devastating.

A parent of a boy with bipolar disorder described learning to manage mood triggers:

FAMILY PERSPECTIVES

FAMILY PERSPECTIVES

“In the early years of my son’s journey, we tried many options and the learning curve has been steep. Getting consistent and adequate sleep is a must for my son. We all must adjust our schedules to make sure this happens…. And, what may be everyday, normal stress for you and I can be a trigger for those with bipolar. Don’t schedule other life events on top of known stressors …ie, going on vacation right after finals set my son off once.”8

Pharmacologic Treatment

Although only 2 pharmacologic treatments are approved by the FDA to treat depression associated with bipolar disorder in pediatric patients,9–12 several other treatments have been investigated.1,3

Antidepressants. Antidepressant monotherapy is not a safe treatment choice for patients with PBD because it may induce manic symptoms.3 Biederman and colleagues13 conducted a chart review of 59 patients aged 3.5 to 17 years with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. They found that, although antidepressants effectively reduced depressive symptoms in this population, those who received a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) were 3 times more likely to have developed manic symptoms at the next follow-up visit (compared with those patients who did not receive an SSRI). However, antidepressants were not found to inhibit the effect of antimanic treatments. A more recent study by Baumer et al14 also found high rates of antidepressant-induced mania in patients with PBD, as well as increased suicidal ideation. Furthermore, investigators have reported that pediatric patients, especially younger patients, who are at high risk for developing bipolar disorder due to the presence of depressive or anxiety symptoms and having a parent with bipolar I disorder have an increased risk of antidepressant-induced manic symptoms and adverse effects such as irritability, aggression, impulsivity, and hyperactivity.15 Antidepressants, therefore, should be used with caution in patients with a diagnosis of PBD, as well as in those at risk for developing bipolar disorder.3

Mood stabilizers. Limited evidence from open-label trials is available to support the efficacy of lamotrigine or lithium for treating PBD.16,17 Chang and colleagues16 found that, in 19 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years with an episode of bipolar depression, 63% experienced a ≥ 50% reduction in depressive symptoms after 8 weeks of lamotrigine treatment. In a population of 27 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years with an episode of bipolar depression, Patel and colleagues17 found that, after 6 weeks of treatment with lithium, 48% experienced a ≥ 50% reduction in depressive symptoms and 30% experienced remission. Although these results are promising, placebo-controlled trials are needed.1

Antipsychotics. Because quetiapine is an effective treatment for bipolar depression in adults, it has also been studied in adolescent patients;18,19 however quetiapine was found to be no more effective than placebo for reducing the symptoms of bipolar depression.

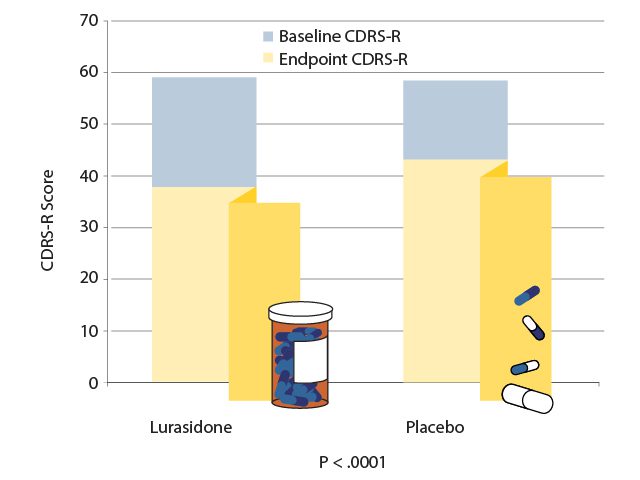

In a 6-week study,11 347 patients aged 10 to 17 years with an episode of bipolar depression were randomly assigned to receive either a flexible dose of lurasidone (20 to 80 mg/d; mean dose 33.6 mg/d) or placebo. At the study endpoint, the patients who had received lurasidone experienced significantly greater reductions in depression as measured by both the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R) and the Clinical Global Impression Bipolar Severity (CGI-BP-S) assessment (P < .0005 for both assessments). These differences in treatment effect became significant after 14 days and remained significant until study endpoint (AV 2). Lurasidone was also significantly superior to placebo on the secondary efficacy measures of improvements in anxiety (P = .0385), global functioning (P < .0001), and quality of life (P = .0044).11 Lurasidone was well-tolerated and few patients discontinued treatments due to adverse events, with the most frequently reported side effects being nausea and somnolence. Lurasidone was found to have little effect on weight or metabolic parameters in this 6-week study.11 Lurasidone is FDA-approved to treat depressive episodes associated with bipolar disorder in pediatric patients.

AV 2. Efficacy of Lurasidone vs Placebo for an Episode of Pediatric Bipolar Depression

Data from Delbello et al.

Combination treatment. The second FDA-approved treatment for PBD is olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (OFC).9 Detke and colleagues12 conducted an 8-week, double-blind study in which 255 patients aged 10 to 17 years who were experiencing a depressive episode associated with bipolar I disorder were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or a flexible dose of OFC. The patients who were receiving treatment with OFC began to show significantly greater improvement than the placebo group after 1 week (P = .02), which continued for the duration of the study. At endpoint, the group receiving OFC showed a significantly greater mean decrease on the CDRS-R than the placebo group did (P = .003). The most commonly reported adverse events were weight gain, appetite increase, headache, and somnolence. The expected weight gain for a patient treated with OFC for 8 weeks was estimated to be 5.1 kg, compared with 0.6 kg for a patient receiving placebo (P < .001). Other adverse events that were significantly more common in the OFC group than in the placebo group included increases in all cholesterol measures, prolactin levels, heart rate, and QTc (P < .001 for all).12

CASE PRACTICE QUESTION

CASE PRACTICE QUESTION

Case 1. Alex is a 12-year-old boy who presents with anhedonia, depressed mood, poor sleep, decreased appetite, and suicidal ideation. He has a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and had a 10-day episode of mania earlier this year, for which he was hospitalized. Which of the following is an evidence-based, effective, and well-tolerated treatment for Alex?

- Lithium

- Lamotrigine

- Quetiapine

- Lurasidone

DISCUSSION OF CASE PRACTICE QUESTIONS

DISCUSSION OF CASE PRACTICE QUESTIONS

Preferred response is d. Lurasidone

Explanation: Although some open-label data are available indicating efficacy of lithium and lamotrigine, no double-blind, placebo-controlled data have been obtained, which is the gold standard for evidence-based, effective and well-tolerated treatments. For quetiapine, the two double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have been negative in children and adolescents with bipolar depression. Therefore, the correct answer is (d) because lurasidone was found in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study to be more effective than placebo for acute bipolar depression in adolescents.

Finding the best medication regimen may take time. Mothers expressed their feelings about dealing with their daughters’ bipolar disorder and accepting the need for medication:

FAMILY PERSPECTIVES

FAMILY PERSPECTIVES

“Here we are, seven years after diagnosis, and still trying to figure out the right medications to help her get better. Trying to medicate a hormonal, chronically sleep deprived 14-year-old is like hitting a moving target. We believe a big piece of the puzzle is sleep deprivation, but it is difficult to fix when she won’t tell us the truth about sleep patterns.”20

“We began the long process of finding the right pharmacological cocktail to get her stable. Meanwhile, as the search for medication continued, my daughter’s therapist recommended a strict regimen for my daughter, including regular times for eating, sleeping, and exercise. … Unfortunately, until my teen was stable, getting her to do anything at any time was like trying to move boulders. … It was hard to be told of all the things I should be doing, when some days the most I could do was keep her from jumping out the windows, running down the winter streets barefoot and in pajamas, or cutting all her hair off (actually, I was unable to prevent her from doing any of these things, although I tried). Eventually, after much trial and error, her doctor found the right mix of medication.”21

“We had many sleepless nights and lots of tears. The stress of dealing with this reality and trying to keep our lives as normal as possible was immense. At times, it still is.… She takes a lot of medication, but we have accepted that she is better with them than she is without them.”22

Transitioning to Adult Care

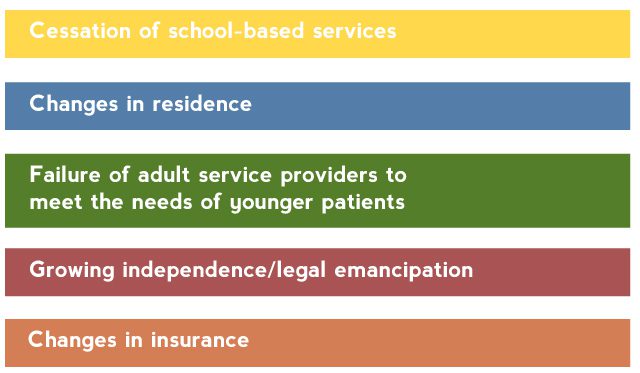

Many young patients lose contact with their mental health providers as they age out of child mental health systems.23 Young patients encounter numerous barriers to obtaining adult care (Table 1).24

Table 1. Barriers to Continuity of Mental Health Services During the Transition to Adulthood

Based on Hower et al.24

Among patients with bipolar disorder, use of all types of mental health services, including visits for pharmacotherapy and for individual and group psychosocial therapy, have been found to decline, sometimes precipitously, after age 18 years.24 Patients with bipolar disorder need coordinated transition of care from pediatric to adult services.25 Clinicians who treat pediatric patients with bipolar disorder must take a more proactive approach in ensuring that these patients experience a smooth transition to appropriate adult services.

To effectively assist in this transition, clinicians must understand the needs and preferences of this population. Many adolescents with mental health issues are apprehensive about leaving the care they are familiar with; to ease the transition, the change should be made gradually.25 The transition should be viewed as a process, rather than a sudden switch from the child provider to the adult provider; child providers can keep patients under their care, even if they are older than 18 years, as patients begin transitioning to adult provider settings. Although parents may still be involved in treatment and an important source of support, this age group wants to be involved in their own treatment and to have their opinions and desires recognized.25 Also, as these individuals are entering adulthood, they need help managing the unique tasks associated with this transitional age, but adult mental health services are often poorly equipped to provide developmentally appropriate services. Clinicians must either provide or help find care for transition-age patients that prepares them for managing their illness in adulthood, including self-advocacy and use of social supports.25

Conclusion

Pediatric bipolar disorder has a profound impact on not only the patient but also the patient’s family. Psychosocial treatment that involves the family and provides education about the disorder, as well as effective coping and management strategies, is crucial. Pharmacologic treatment is difficult because data from clinical trials are limited, but 2 FDA-approved treatments with established efficacy are available and should be considered as first-line treatments. By following these management strategies, clinicians can help patients and families improve outcomes.

Clinical Points

- When planning treatment for pediatric bipolar disorder, include nonpharmacologic interventions that incorporate family involvement, education, and self-management strategies.

- Avoid using antidepressant monotherapy for bipolar disorder to prevent a switch into mania.

- Consider FDA-approved agents for depression in bipolar youth as first-line options.

- Closely monitor pediatric patients for adverse events associated with pharmacologic treatment for bipolar disorder.

- Continue to provide care to young patients as they gradually transition from pediatric to adult care.

To learn about the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents, see the other activity in this series, Using Screening Tools and Diagnosing Bipolar Disorder in Pediatric Patients, by Manpreet K. Singh, MD, MS.

Find more articles on this and other psychiatry and CNS topics:

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders

Abbreviations

ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

CDRS-R = Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised

CGI-BP-S = Clinical Global Impression Bipolar Severity

FDA = US Food and Drug Administration

OFC = olanzapine/fluoxetine combination

PBD = pediatric bipolar disorder

SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

References

- Cosgrove VE, Roybal D, Chang KD. Bipolar depression in pediatric populations: epidemiology and management. Paediatr Drugs. 2013;15(2):83–91. PubMed doi:10.1007/s40272-013-0022-8

- Van Meter AR, Henry DB, West AE. What goes up must come down: the burden of bipolar depression in youth. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):1048–1054. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.039

- Goldstein BI, Birmaher B, Carlson GA, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force report on pediatric bipolar disorder: Knowledge to date and directions for future research. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(7):524–543. PubMed doi:10.1111/bdi.12556

- Fristad MA, MacPherson HA. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent bipolar spectrum disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43(3):339–355. PubMed doi:10.1080/15374416.2013.822309

- MacPherson HA, Ruggieri AL, Christensen RE, et al. Developmental evaluation of family functioning deficits in youths and young adults with childhood-onset bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2018;235:574–582. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.078

- Miklowitz DJ, Chung B. Family-Focused Therapy for Bipolar Disorder: Reflections on 30 Years of Research. Fam Process. 2016;55(3):483–499. PubMed doi:10.1111/famp.12237

- Miklowitz DJ. Evidence-based interventions for adolescents and young adults with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(suppl E1):e05.

- When your child is diagnosed with bipolar disorder. bp Magazine. July 20, 2018. Available at https://www.bphope.com/kids-children-teens/when-your-child-is-diagnosed-with-bipolar-disorder/. Accessed December 2018.

- Symbyax [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN; Eli Lilly & Co., 2017.

- Latuda [package insert]. Marlborough, MA; Sunovion, 2018.

- DelBello MP, Goldman R, Phillips D, et al. Efficacy and safety of lurasidone in children and adolescents with bipolar I depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(12):1015–1025. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.10.006

- Detke HC, DelBello MP, Landry J, et al. Olanzapine/fluoxetine combination in children and adolescents with bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(3):217–224. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.012

- Biederman J, Mick E, Spencer TJ, et al. Therapeutic dilemmas in the pharmacotherapy of bipolar depression in the young. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2000;10(3):185–192. PubMed doi:10.1089/10445460050167296

- Baumer FM, Howe M, Gallelli K, et al. A pilot study of antidepressant-induced mania in pediatric bipolar disorder: characteristics, risk factors, and the serotonin transporter gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(9):1005–1012. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.010

- Strawn JR, Adler CM, McNamara RK, et al. Antidepressant tolerability in anxious and depressed youth at high risk for bipolar disorder: a prospective naturalistic treatment study. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(5):523–530. PubMed doi:10.1111/bdi.12113

- Chang K, Saxena K, Howe M. An open-label study of lamotrigine adjunct or monotherapy for the treatment of adolescents with bipolar depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(3):298–304. PubMed doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000194566.86160.a3

- Patel NC, DelBello MP, Bryan HS, et al. Open-label lithium for the treatment of adolescents with bipolar depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(3):289–297. PubMed doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000194569.70912.a7

- DelBello MP, Chang K, Welge JA, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of quetiapine for depressed adolescents with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(5):483–493. PubMed doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00728.x

- Findling RL, Pathak S, Earley WR, et al. Efficacy and safety of extended-release quetiapine fumarate in youth with bipolar depression: an 8 week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(6):325–335. PubMed doi:10.1089/cap.2013.0105

- “Sticking It Out” with Your Child’s Bipolar Journey. bp Magazine. September 17, 2018. Available at https://www.bphope.com/kids-children-teens/mom-parents-kids-bipolar-not-lose-heart/. Accessed December 2018.

- A Single Mother’s Journey: A ‘Brave’ Teenage Daughter’s Bipolar Diagnosis. bp Magazine. September 22, 2017. Available at https://www.bphope.com/kids-children-teens/a-single-mothers-journey-a-brave-teenage-daughters-bipolar-diagnosis/. Accessed December 2018.

- One Mom Balances “Fixing” and Accepting Daughter’s Bipolar Diagnosis. bpHope. November 27, 2017. available at https://www.bphope.com/kids-children-teens/one-mom-balances-fixing-and-accepting-daughters-bipolar-diagnosis/. Accessed December 2018.

- Pottick KJ, Warner LA, Vander Stoep A, et al. Clinical characteristics and outpatient mental health service use of transition-age youth in the USA. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2014;41(2):230–243. PubMed doi:10.1007/s11414-013-9376-5

- Hower H, Case BG, Hoeppner B, et al. Use of mental health services in transition age youth with bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(6):464–476. PubMed doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000438185.81983.8b

- Burnham Riosa P, Preyde M, Porto ML. Transitioning to adult mental health services: perceptions of adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems. J Adolesc Res. 2015;30(4):446–476. doi:10.1177/0743558415569730

© Copyright 2018 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Save

Cite