Abstract

Measurement-based care (MBC) is an important strategy in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder who have inadequate antidepressant response. The rating scales used in MBC can assist clinicians at critical decision points, such as when to declare a treatment failure, what to do with partial improvement, and how long to continue successful treatment. Measurement has two benefits: it gives the clinician an objective basis for comparison of symptom severity over time, and it helps patients to have insight into their illness course. Further, many of these tools do not add substantially to the length of the clinical visit. MBC can also be used to monitor and address residual symptoms such as fatigue and irritability that impact patients’ functioning and quality of life.

This activity is the second of four included in the series “Inadequate Response to Antidepressant Treatment in Major Depressive Disorder”:

- Recognizing Inadequate Response in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder

- Inadequate Response to Treatment in Major Depressive Disorder: Augmentation and Adjunctive Strategies

- Overcoming Challenges to Treat Inadequate Response in Major Depressive Disorder

Financial support was provided by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., and Lundbeck, Inc.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas (Dr Trivedi); Massachusetts General Hospital Clinical Trials Network and Institute, Boston, Massachusetts (Dr Papakostas); Departments of Psychiatry and Family Medicine, University of Tennessee College of Medicine, Memphis, Tennessee (Dr Jackson); and Department of Psychiatry, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois (Dr Rafeyan)

Financial disclosure

Dr Papakostas has been a consultant for AlphaSigma, Cala Health, Alkermes, Johnson & Johnson, and Otsuka and has received honoraria from Acadia, AlphaSigma, Alkermes, and Hypera S.A. Dr Jackson has been a consultant and speakers/advisory board member for and received honoraria from Allergan, Genentech, Otsuka, and Sunovion. Dr Rafeyan has received grant/research support from Eli Lilly, Sepracor, and Janssen and has been a speakers/advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Allergan, Alkermes, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Intra Cellular Therapies, Pfizer, Abbott, Otsuka, Lundbeck, Takeda, Teva, and Sunovion. Dr Trivedi has been a consultant or advisory board member for Allergan, Alto Neuroscience, Applied Clinical Intelligence, Axsome Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Engage Health Media, GreenLight VitalSign6, Janssen, Lundbeck Research USA, Navitor, Otsuka, Perception Neuroscience, Pharmerit International, SAGE Therapeutics, and Signant Health; has received grant/research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas; and has received editorial compensation from the American Psychiatric Association (Deputy Editor, American Journal of Psychiatry) and Oxford University Press.

This eReport is derived from the expert roundtable meeting “Inadequate Response to Antidepressant Treatment in Major Depressive Disorder,” which was held October 5, 2019.

This evidence-based peer-reviewed eReport was prepared by Healthcare Global Village, Inc. Financial support for preparation and dissemination of this eReport was provided by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc., and Lundbeck, Inc., for educational purposes. The faculty acknowledges Evonne Krell for editorial assistance in developing the eReport. The opinions expressed herein are those of the faculty and do not necessarily reflect the views of Healthcare Global Village, Inc., the publisher, or the commercial supporters.

To cite: Trivedi MH, Papakostas GI, Jackson WC, et al. Implementing measurement-based care to determine and treat inadequate response. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):OT19037BR1.

To share: https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.OT19037BR1

Meet the faculty

Introduction

At a roundtable meeting, an expert panel discussed how to determine where major depressive disorder (MDD) patients are on the response continuum and how to proceed with treatment when a patient experiences inadequate antidepressant response. Their discussion is interspersed in video clips throughout this activity, which outlines how measurement-based care (MBC) can help clinicians improve outcomes in patients with MDD.

Measurement-Based Care

Despite new treatments for major depressive disorder (MDD), only about one-third of patients achieve remission,1 so clinicians have to be thinking about how best to manage a large proportion of patients who are not getting well with the first treatment. An important strategy to address this is measurement-based care (MBC), which will guide clinical decision-making and help educate patients so that they can be involved in treatment decisions.

MBC is a means of assisting the implementation of evidence-based care for MDD. It includes assessment tools, use of a multistep decision tree–based algorithm, patient follow-up, and feedback (ie, a systematic process in which progress and outcome data are gathered and interpreted to aid in treatment decisions) (AV 1).

AV1. Elements of Measurement-Based Care

Benefits of Measurement-Based Care

Some clinicians may feel like they do not have time to implement assessment tools.2 However, self-report scales can actually be a time-saver, as they can be completed before the clinician visit and allow the clinician to focus the visit on specific areas already reported. Another benefit of these assessments, discussed by Drs Trivedi and Jackson, is that patients may be more honest on self-rated scales than in a face-to-face interview, especially if they feel stigmatized or judged in areas like suicidality or substance abuse. The value of MBC can also be seen in improved outcomes and better-informed treatment decisions. The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study showed that MBC may lead to greater remission rates in patients with chronic depression.1 It should be remembered, as Dr Jackson pointed out, that MBC is not a substitute for clinical judgment.

Video 1: Dr Trivedi Outlines How Measurement-Based Care Will Guide Treatment Decisions

If symptoms and response are not measured over time, there may be a greater likelihood that the patient will be left for months, or even years, on inefficient or inadequate treatment. In a December 2019 interview with the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, one patient expressed frustration with a lack of improvement in her symptoms:

Patient Perspective

Patient Perspective

“Trying to explain it to the doctor or to different doctors, if I feel like I’m not getting anywhere, it gets very tiresome…It does get very frustrating when it’s been years and years and years.”

Rating Scales

The rating scales used in MBC can assist clinicians at critical decision points, such as when to declare a treatment failure, what to do with partial improvement, and how long to continue successful treatment. Rating scales can be used to gauge the level of treatment response. For example, the STAR*D trial3 used the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology4 clinician-rated total score of ≥9 for nonresponse, 6–8 for partial response, and ≤5 for remission. These ratings were correlated with a dose change or continuation. This approach can be applied with other rating scales, such as the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).5 The important thing is to use a measurement tool for symptoms at baseline and regular follow-up visits, and then use the results to guide treatment decisions, whether or not one is adhering to an algorithm/guidelines (for more on use of guidelines in decision-making, see the activity “Inadequate Response to Treatment in Major Depressive Disorder: Augmentation and Adjunctive Strategies”).

Although the acute phase represents an essential decision-making point, decision-making continues in the maintenance phase. It is often the case that even in the continuation phase and in the long term, there are periods in patients’ lives in which their functional impairment or symptoms return. If the clinical response to these instances is guided by measurements, decision-making becomes easier. Dr Rafeyan pointed out that measurement has two benefits: it gives the clinician an objective basis for comparison of symptom severity over time, and it helps patients to have insight into their illness course. The better educated patients are about these measurements, the more focused they tend to be with adhering to a treatment plan.

Video 2: Dr Rafeyan Describes the Benefits of Implementing Measurements in Clinical Practice

Reference: Hamilton et al.6

Abbreviation: HAM-D=Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

Response and Remission

Response is generally defined as a predefined percent decrease (often 50%) in symptoms from baseline on a depression severity rating scale.7 While response is typically a 50% decrease in symptoms, remission is a predefined cutoff score on depression severity rating scale indicating that the symptoms are almost all gone, such as a PHQ-9 score of less than 5. 7 Patients in remission may have some occasional symptoms, but otherwise, they are recovered. Most often, remission is associated with significant improvement in patients’ function and quality of life. Because of its implications for better prognosis and function in patients with MDD, remission should be the goal of MDD treatment.7

Clinicians must be aware that the timing of treatment assessment influences outcomes. For example, patients who switch treatments rapidly, such as in the first 2–4 weeks of antidepressant therapy because they or their clinicians decide treatment is not working, may not have been given adequate time to receive the benefit of the initial treatment. Even worse is when patients are put back on an ineffective medication, as was the case for the following patient:

Patient Perspective

Patient Perspective

“I’ve been on many different antidepressants. Even was told to try the same thing again, knowing in the past that it didn’t work.…They feel I should go back on it again, thinking that it’ll probably have a different effect this time around.”

Problem of Inadequate Treatment

Video 3: Drs Trivedi, Papakostas, and Jackson Discuss the Problem of Inadequate Treatment

STAR*D trial results showed that patients will achieve response and remission all the way up to 10 or 12 weeks with initial treatment.1 If those patients on week 10 or 12 had been stopped at the end of 2 or 3 weeks, they would have been unnecessarily moved to the next treatment. Rating instruments used regularly will provide clinicians with results over time so they are able to make decisions with a view to the illness course. Clinicians should be mindful of not switching too rapidly and not continuing inadequate treatment for too long. When patients decide to start treatment for depression, it is the clinician’s task to work with the patient and make treatment decisions in a responsive fashion, at the right time, so that the patient does not have to endure long periods of incomplete improvement. Dr Trivedi commented that measurements are just the first step, but they provide important information for clinicians to integrate with their judgment and experience into decision-making.

Assessment of Residual Symptoms

Even when patients achieve response or remission, residual symptoms can remain troublesome; MBC can help in the detection of these so that treatment can be adjusted as necessary.

In addition to measuring the core depressive symptoms, clinicians may need to add other itemized rating instruments to track symptoms such as suicidality or irritability. Rating scales such as the Concise Assessment Symptom Tracking (CAST) scale8 and Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale9 can be used for suicidality, and the CAST scale also measures irritability as 1 of 5 negative symptom domains associated with significant treatment implications.10

Dr Trivedi noted that irritability can be a key, problematic residual symptom. A proportion of patients will present with irritability that is independent of the other 9 core symptoms of depression.11 Even if these patients have achieved response or remission on the standard rating instruments, they are likely to have faster relapse and recurrences, which is why clinicians should have a strategy for tracking this symptom. In the Combining Medications to Enhance Depression Outcomes (CO-MED) trial,11 higher reduction in CAST irritability domain subscale score predicted a higher likelihood of remission and a lower likelihood of no meaningful benefit.

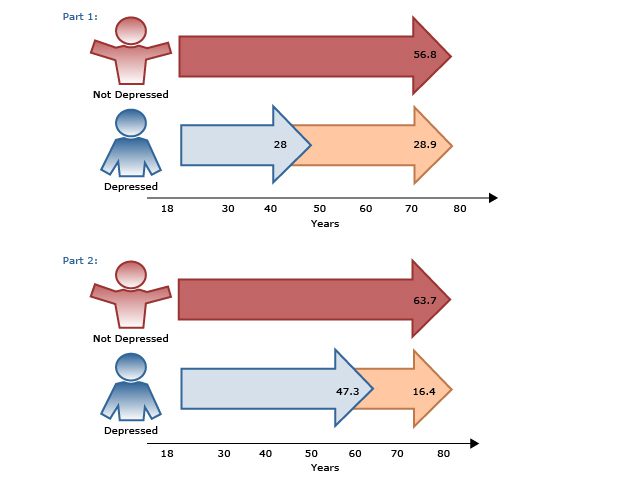

Assessment of Patient Functioning

Ultimately, patients are often more focused on improvement in their functioning, quality of life, and work productivity, while clinicians’ focus tends to be on symptom improvement. In the CO-MED trial,12 work productivity was measured using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment self-report questionnaire in 331 employed patients with MDD. The results showed that work productivity improved with acute-phase antidepressant treatment and that this improvement predicted long-term changes in depression severity and remission status (AV 2). Also in the CO-MED trial,13 quality of life began improving in patients as early as week 4, independent of depression severity, and normal quality of life at week 4 was associated with 2 to 6 times higher remission rates.

AV 2. Work Impairment in Depressed Outpatients (N=331) During Acute-Phase Antidepressant Treatment

Data from Jha et al.12

Clinicians should remember that even when patients’ symptoms improve, residual impairments in work productivity and quality of life may still need to be addressed via pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic management.

Self-report measures are available to see how patients with MDD are doing at work and feeling overall. The World Health Organization 5-item Well-Being Index (WHO-5) is a short questionnaire with 5 simple questions to assess subjective well-being.14 The scale can be used as a screening tool for depression and has applications in other study fields, including suicidality. For example, a review reported that individuals attempting suicide and those with suicidal ideation generally have low scores on WHO-5.14 Dr Jackson noted that he uses the WHO-5 for each patient, each visit, to underscore the importance of increasing well-being while simultaneously decreasing symptoms. Administration of the WHO-5 can further open up conversations about nonpharmacologic and lifestyle interventions that may be helpful.

Benefits of Measuring QoL and Wellness

Video 4: Dr Jackson Shares the Benefits of Measuring Patients’ Quality of Life and Wellness

Conclusion

MBC is critical for helping clinicians to make informed and timely treatment decisions and to identify inadequate response early. Administration of self- or clinician-rated scales allows patients to communicate clearly and honestly and can improve adherence by providing patients with insight into their symptoms and illness course. Finally, MBC can help clinicians assess residual symptoms as well as work productivity and overall quality of life to help patients with depression return to their previous lives and levels of functioning.

Case Practice Question

Case Practice Question

Richard is a 59-year-old man, who is married with 2 adult children. He has been a school teacher for 35 years. He had his first onset of depressive symptoms at age 50 and was diagnosed with MDD at age 51. He was successfully treated with fluoxetine, which he discontinued after 2 years due to full remission. Beginning 6 months ago, depressive symptoms returned. His current symptoms include fatigue and irritability during the day, insomnia (sleeping around 4 hours/night), decreased concentration, and weight gain. He was restarted on fluoxetine, which was increased to 40 mg/d after 6 weeks. He showed some improvement (approximately 25% based on self-report rating scale), but he continued to complain of residual symptoms (insomnia, fatigue, and irritability, which were slightly improved). After 4 more weeks, bupropion XL was added (150 mg/d), and he has been on this combination for 1 month. He reports that he has not missed work but feels underproductive and concerned about how his students are being affected; his relationship with his spouse is also becoming strained.

a. No reduction in any depressive symptoms since starting treatment

b. Some improvement in depressive symptoms but continued residual symptoms, with additional concerns about productivity and quality of life

c. Greater than 50% reduction of depressive symptoms and no residual symptoms

d. Noncompliance with medication

Discussion of the Case Practice Question

Discussion of the Case Practice Question

Preferred response: B. Some improvement in depressive symptoms but continued residual symptoms, with additional concerns about productivity and quality of life

Explanation: Based on a self-report rating scale, Richard has shown about 25% improvement, which is inadequate in terms of response and remission criteria. In addition, he reports additional challenges resulting from his depression, including decreased work productivity and decreased quality of life in terms of personal relationships.

Clinical Points

Clinical Points

- Use MBC to assist at critical decision points in treatment.

- Monitor and address residual symptoms such as fatigue and irritability that impact patients’ functioning and quality of life.

© Copyright 2020 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

References (14)

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al; STAR*D Study Team. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28–40. PubMed CrossRef

- Busner J, Kaplan SL, Greco N 4th, et al. The use of research measures in adult clinical practice. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(4):19–23. PubMed

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Gaynes BN, et al. Maximizing the adequacy of medication treatment in controlled trials and clinical practice: STAR(*)D measurement-based care. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(12):2479–2489. PubMed CrossRef

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–583. PubMed CrossRef

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. PubMed CrossRef

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23(1):56–62. PubMed CrossRef

- Rush AJ, Kraemer HC, Sackeim HA, et al; ACNP Task Force. Report by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(9):1841–1853. PubMed CrossRef

- Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Morris DW, et al. Concise Associated Symptoms Tracking scale: a brief self-report and clinician rating of symptoms associated with suicidality. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(6):765–774. PubMed CrossRef

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. PubMed CrossRef

- Jha MK, Minhajuddin A, South C, et al. Worsening anxiety, irritability, insomnia, or panic predicts poorer antidepressant treatment outcomes: clinical utility and validation of the Concise Associated Symptom Tracking (CAST) Scale. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;21(4):325–332. PubMed CrossRef

- Jha MK, Minhajuddin A, South C, et al. Irritability and its clinical utility in major depressive disorder: prediction of individual-level acute-phase outcomes using early changes in irritability and depression severity. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(5):358–366. PubMed CrossRef

- Jha MK, Minhajuddin A, Greer TL, et al. Early improvement in work productivity predicts future clinical course in depressed outpatients: findings from the CO-MED Trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(12):1196–1204. PubMed CrossRef

- Jha MK, Greer TL, Grannemann BD, et al. Early normalization of quality of life predicts later remission in depression: findings from the CO-MED trial. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:17–22. PubMed CrossRef

- Topp CW, Østergaard SD, Søndergaard S, et al. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(3):167–176. PubMed CrossRef

Save

Cite