Article Abstract

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Creditâ„¢. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Note: The American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) accepts certificates of participation for educational activities certified for AMA PRA Category 1 Creditâ„¢ from organizations accredited by ACCME or a recognized state medical society. Physician assistants may receive a maximum of 1.0 hour of Category I credit for completing this program.

Drs Tsai, Kaur, and Gopalakrishna have no personal affiliations or financial relationships with any commercial interest to disclose relative to this article.

The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference is a weekly event in which physicians and staff discuss challenging and/or teaching cases of patients seen at the Institute’s Stead Family Memory Clinic. These conferences are attended by a multidisciplinary group that includes Banner Alzheimer’s Institute dementia specialists, community physicians (internal medicine, family medicine, and radiology), physician assistants, social workers, nurses, medical students, residents, and fellows. The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute located in Phoenix, Arizona, has an unusually ambitious mission: to end Alzheimer’s disease without losing a generation, set a new standard of care for patients and families, and forge a model of collaboration in biomedical research. The Institute provides high-level care and treatment for patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and related disorders. In addition, the Institute offers extensive support services for families and many unique and rewarding research opportunities.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors, not of Banner Health or Physicians Postgraduate Press.

Case Conference

The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute Case Conference is a weekly event in which physicians and staff discuss challenging and/or teaching cases of patients seen at the Institute’s Stead Family Memory Clinic. These conferences are attended by a multidisciplinary group that includes Banner Alzheimer’s Institute dementia specialists, community physicians (internal medicine, family medicine, and radiology), physician assistants, social workers, nurses, medical students, residents, and fellows. The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute located in Phoenix, Arizona, has an unusually ambitious mission: to end Alzheimer’s disease without losing a generation, set a new standard of care for patients and families, and forge a model of collaboration in biomedical research. The Institute provides high-level care and treatment for patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and related disorders. In addition, the Institute offers extensive support services for families and many unique and rewarding research opportunities.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(5):19alz02544

To cite: Tsai P-H, Kaur G, Gopalakrishna G. No MMSE for you! A case of an “uncooperative” patient with early-onset dementia. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2019;21(5):19alz02544.

To share: https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.19alz02544

© Copyright 2019 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: August 1, 2019; accepted September 11, 2019.

Published online: October 24, 2019.

Po-Heng Tsai, MD, is a behavioral neurologist and dementia specialist at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute and a clinical assistant professor of neurology at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Phoenix.

Gurmehr Kaur, MD, is a second-year resident at the University of Arizona College of

Medicine-Phoenix Psychiatry Residency Program at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.

Ganesh Gopalakrishna, MD, is a geriatric psychiatrist and dementia specialist at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute and a clinical associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Phoenix.

*Corresponding author: Po-Heng Tsai, MD, Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, 901 E Willetta St, Phoenix, AZ 85006 ([email protected]).

This CME activity is expired. For more CME activities, visit cme.psychiatrist.com.

Find more articles on this and other psychiatry and CNS topics:

The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders

CME Background

Articles are selected for credit designation based on an assessment of the educational needs of CME participants, with the purpose of providing readers with a curriculum of CME articles on a variety of topics throughout each volume. This special series of case reports about dementia was deemed valuable for educational purposes by the Publisher, Editor in Chief, and CME Institute staff. Activities are planned using a process that links identified needs with desired results.

To obtain credit, read the article, correctly answer the questions in the Posttest, and complete the Evaluation. A $10 processing fee will apply.

CME Objective

After studying this article, you should be able to:

- Implement a process using history, interview, and assessment tools for diagnosing patients suspected of having Alzheimer’s disease

Accreditation Statement

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit Designation

The CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Creditâ„¢. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Note: The American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) accepts certificates of participation for educational activities certified for AMA PRA Category 1 Creditâ„¢ from organizations accredited by ACCME or a recognized state medical society. Physician assistants may receive a maximum of 1.0 hour of Category I credit for completing this program.

Release, Expiration, and Review Dates

This educational activity was published in October 2019 and is eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Creditâ„¢ through October 31, 2021. The latest review of this material was October 2019.

Financial Disclosure

All individuals in a position to influence the content of this activity were asked to complete a statement regarding all relevant personal financial relationships between themselves or their spouse/partner and any commercial interest. The CME Institute has resolved any conflicts of interest that were identified. In the past year, Larry Culpepper, MD, MPH, Editor in Chief, has been a consultant for Alkermes, Harmony Biosciences, Merck, Shire, Supernus, and Sunovion. No member of the CME Institute staff reported any relevant personal financial relationships. Faculty financial disclosure appears below.

HISTORY OF PRESENTING ILLNESS

Ms A is a 60-year-old right-handed woman who presented to Banner Alzheimer’s Institute (BAI) in October 2018 with her family for evaluation and treatment of cognitive complaints. She was initially seen at BAI by another provider in January 2017. Cognitive symptoms reportedly began in 2013 with paranoia, which was possibly related to poor memory (eg, accused family members of moving her things around to deliberately confuse her). Her living environment was described as very stressful. There was concern regarding the reliability of her history because Ms A provided little spontaneous contribution, and the family member who accompanied her was noted to be vague. It was also difficult to assess her functionality. Ms A stopped driving because of “a panic attack” and could not cook because she was unable to recall recipes. However, she claimed that she “takes care of everyone else.” The accompanying family member readily endorsed depression and anxiety.

Ms A had a neurologic evaluation with an outside provider 1 year prior to her initial presentation at BAI that included a neuropsychological evaluation, electroencephalogram, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. The reports were noted to be inconclusive and did not point toward a specific diagnosis. At the bedside cognitive assessment during the initial visit to BAI, she scored 10 out of 30 points on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al, 1975). The examiner expressed concern for lack of effort and inconsistency. Her neurologic examination was normal. The BAI provider at the initial visit in 2017 concluded that it was difficult to arrive at a definitive diagnosis due to lack of (1) a reliable collateral history, (2) an accurate assessment of the patient’s current abilities and limitations, and (3) access to historical data in the form of an MRI and neuropsychological testing. His plan was to obtain old records and update testing with an MRI of the brain as well as neuropsychological evaluation. The patient was then lost to follow-up until the current visit. She did have a repeat neuropsychological evaluation but did not have a repeat MRI of the brain.

At the current visit to BAI in 2018, Ms A’s family reported that she previously worked as a dental hygienist and then in the family restaurant but stopped volitionally in 2011 to help take care of her grandson. Her symptoms first became noticeable in 2015 when she became increasingly fearful of driving. In 2017, she began to have difficulty with reading and writing. She also began reporting that she was being deprived of water and food and that she was being forced to take her medications. When family visited her home at this time, she was found to be living in unsanitary conditions with no water or electricity, so she had to move in with her sister. After the change in her living situation, she had significant improvement in her appearance and some improvements in her functionality (eg, was able to read and write again). She required assistance with financial and medication management, transportation, and meal preparation. She remained independent in basic activities of daily living. Ms A had no aggressive behaviors, personality changes, or sleep disturbance.

PAST MEDICAL HISTORY

Ms A has a history of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, fibromyalgia, migraine, arthritis, back pain, depression, and anxiety. She denied any past surgical history. She also denied any history of stroke, seizure, head injury, or substance abuse.

ALLERGIES

Ms A is allergic to acetaminophen/oxycodone (Percocet).

MEDICATIONS

Ms A’s current medication includes gemfibrozil 600 mg twice daily.

SOCIAL HISTORY

Ms A was born and raised in Mexico but moved to Arizona at age 8 years. She completed 14 years of education, including 2 years of college. She worked previously as a dental hygienist and ran her own businesses. She has been married for 30 years.

SUBSTANCE USE HISTORY

There is no known alcohol, tobacco, or recreational drug use.

FAMILY HISTORY

Ms A’s mother died due to a myocardial infarction. Her siblings have hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Her paternal aunt has a history of Parkinson disease, and her maternal aunt has a history of an unknown psychiatric illness.

PHYSICAL AND NEUROLOGIC EXAMINATION

Ms A’s physical examination revealed mild hypertension with blood pressure of 139/96 mm Hg but was otherwise unremarkable. She was awake and alert. Her affect was somewhat blunted with decreased engagement with the examiner. Her speech was mostly fluent with occasional word search pauses. Comprehension was grossly intact. On neurologic examination, her pupils were round and reactive to light. She did not participate in extraocular movement testing. Her face was symmetric, and her hearing was adequate for interview and examination. Her palate was elevated symmetrically. She did not want to protrude out her tongue. Tone was normal in the bilateral upper extremities, and she had symmetric movements of the upper and lower extremities. She refused to perform finger-nose-finger or heel-to-shin maneuvers. She had erect posture. Her gait was slightly cautious but largely fluid with good arm swings.

LABORATORY, RADIOLOGY, AND NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL EVALUATION RESULTS

Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and thyroid-stimulating hormone, free T4, vitamin B12, folic acid, and rapid plasma reagin tests performed after the initial visit were within normal limits. An MRI of the brain with and without contrast performed about 8 months prior to the initial visit was interpreted by the radiologist as normal. An automated brain volumetry software program indicated normal hippocampal volume according to the software’s age and sex-matched normative data.

Ms A had 2 neuropsychological evaluations. The first was done 7 months prior to the BAI initial visit in 2017 and demonstrated diffuse and severe cognitive impairments; however, standalone and embedded measures suggested suboptimal effort. The second evaluation took place 10 months after the initial visit to BAI. The repeat testing again demonstrated global impairment. It was noted by the neuropsychologist that Ms A was putting forth her best effort with normal frustration tolerance, and the evaluation results were judged to be reliable.

BEDSIDE COGNITIVE ASSESSMENT

Ms A refused to participate in bedside cognitive assessments. Review of her MMSE (Folstein et al, 1975) performance at the initial visit in 2017 demonstrated she had difficulty with essentially all cognitive domains. Scores ≥ 24/30 are generally indicative of normal cognition, however, are highly influenced by level of education and to a lesser extent by age (Crum et al, 1993). Ms A scored 10/30 and demonstrated difficulties in orientation (4 points lost), as well as deficits in registration, attention and comprehension, and drawing, scoring 0 points in each of those sections. She also demonstrated some impairment in recall (losing 2 out of 3 points) and in language with difficulty repeating phrases and following written commands.

Ms A also completed the clock drawing test (Shulman, 2000). Ms A’s clock drawing demonstrated a normal circle but no placement of numbers or clock hands (Figure 1).

Click figure to enlarge

Ms A had a significant cognitive and functional decline as reported by her family. In addition, she demonstrated impairments in multiple cognitive domains on both bedside and neuropsychological evaluation. One concern in determining whether she meets criteria for a major neurocognitive disorder is the possibility of an underlying psychiatric disorder considering her bedside demeanor and lack of cooperation in testing.

The DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) defines a major neurocognitive disorder as follows:

- Evidence of significant cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in 1 or more areas of cognitive domains (complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual-motor or social cognition) based on:

- Concern of the individual, a knowledgeable informant, or the clinician that there has been a significant decline in cognitive function and

- Substantial impairment in cognitive performance, preferably documented by standardized neuropsychological testing or, in its absence, another quantified clinical assessment.

- The cognitive deficits interfere with independence in everyday activities.

- The cognitive deficits do not occur exclusively in the context of a delirium.

- The cognitive deficits are not better explained by another mental disorder.

THE TREATING PHYSICIAN’ S IMPRESSION

Based on the history and clinical presentation as well as the results of the cognitive and physical examination, the treating physician felt that Ms A had a major neurocognitive disorder (per DSM-5 criteria).

Ms A would not meet the criteria for probable Alzheimer’s disease because there was no clear-cut history of worsening either by subjective report or objective cognitive assessment; however, she could meet the criteria for possible Alzheimer’s disease. A dementia can be classified as probable Alzheimer’s disease when the patient meets core clinical criteria for all-cause dementia and has characteristics of an insidious or gradual onset of cognitive symptoms over months to years, not sudden over hours or days, with clear-cut history of worsening reported or observed by others. The initial and most prominent cognitive deficits most commonly reflect short-term memory dysfunction, with impairment in learning and recall of recently learned information. There should also be evidence of cognitive dysfunction in at least 1 other cognitive domain, such as reasoning and handling of complex tasks, visuospatial abilities, language functions, or changes in behavior or comportment. Less commonly, nonamnestic presentations occur when the most prominent deficits are in language, visuospatial skills, or executive function.

A diagnosis of possible Alzheimer’s dementia should be made in either of the following circumstances (McKhann et al, 2011):

- Atypical course: Atypical course meets the core clinical criteria in terms of the nature of the cognitive deficits for Alzheimer’s dementia but has either a sudden onset of cognitive impairment or demonstrates insufficient historical detail or objective cognitive documentation of progressive decline.

- Etiologically mixed presentation: Etiologically mixed presentation meets all core clinical criteria for Alzheimer’s disease dementia but has (a) evidence of concomitant cerebrovascular disease, defined by a history of stroke temporally related to the onset or worsening of cognitive impairment, or the presence of multiple or extensive infarcts or severe white matter hyperintensity burden; or (b) features of dementia with Lewy bodies other than the dementia itself; or (c) evidence for another neurologic disease or a non-neurologic medical comorbidity or medication use that could have a substantial effect on cognition.

The determination for etiology was difficult and limited in this case because the cognitive examinations showed global impairment that lacked a specific pattern that could have aided in the differential diagnosis process. Prior MRI of the brain also did not reveal a specific pattern of cerebral atrophy or other structural abnormalities such as cerebrovascular disease that would support a specific diagnosis. Ms A had no dream-enactment behavior, visual hallucinations, or parkinsonism to suggest dementia with Lewy bodies. Behavior variant frontotemporal dementia is possible given her age and behavioral disturbance (ie, paranoia) as the initial presenting symptoms. Additionally, there appears to be some degree of psychiatric or psychological overlay due to inconsistent behavior and interactions, prior history of abusive and neglectful environment, and improvement and reversal of some of the symptoms (eg, now able to read again). One of the neuropsychological evaluations also raised questions regarding issues with effort.

THE TREATING PHYSICIAN’ S PLAN

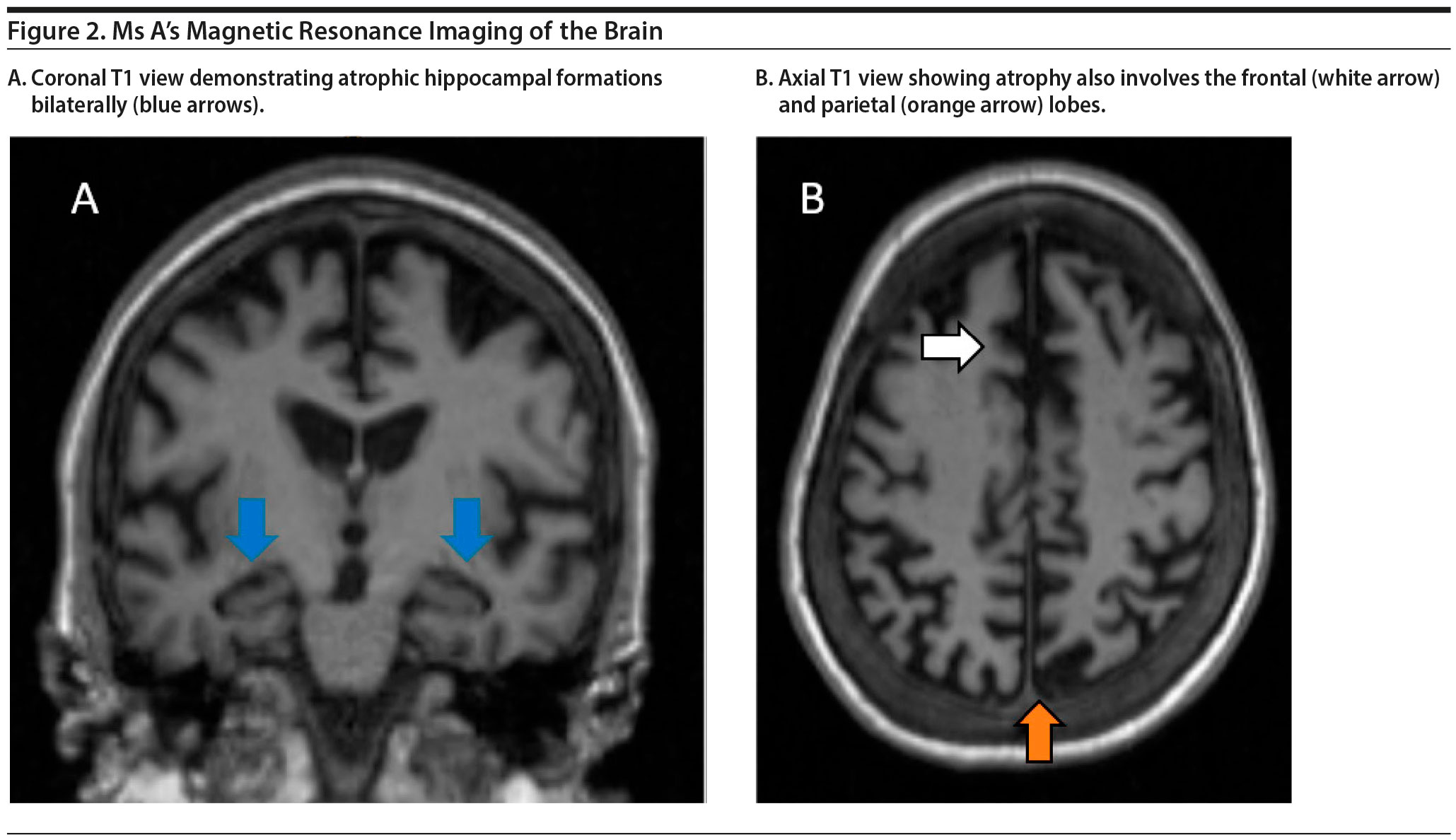

The treating physician decided to obtain repeat MRI of the brain to assess for interval change from the MRI in 2016 and to look for the presence, degree, and pattern of cerebral atrophy, cerebral vascular disease, or other structural abnormalities. If there is predominant frontotemporal cerebral atrophy, it would support frontotemporal dementia as the likely diagnosis. On the other hand, if cerebral atrophy involves medial temporal lobes and hippocampal formations, Alzheimer’s disease is a consideration. If no significant progression or changes were seen, a neurodegenerative process would be less likely. Because she has already had 2 neuropsychological evaluations with both demonstrating global impairment, another neuropsychological evaluation is unlikely to be informative.

Ms A’s MRI of the brain is shown in Figure 2. The results demonstrated a moderate amount of cerebral atrophy with no obvious predominant lobar pattern of volume loss. The hippocampal formations are affected, although not preferentially so.

Because the MRI of the brain demonstrated nonspecific pattern of atrophy, the etiology of Ms A’s dementia remains unclear. However, MRI of the brain did demonstrate progressive atrophy, and the degree of atrophy is more than expected given Ms A’s age. Therefore, an underlying neurodegenerative process is suspected.

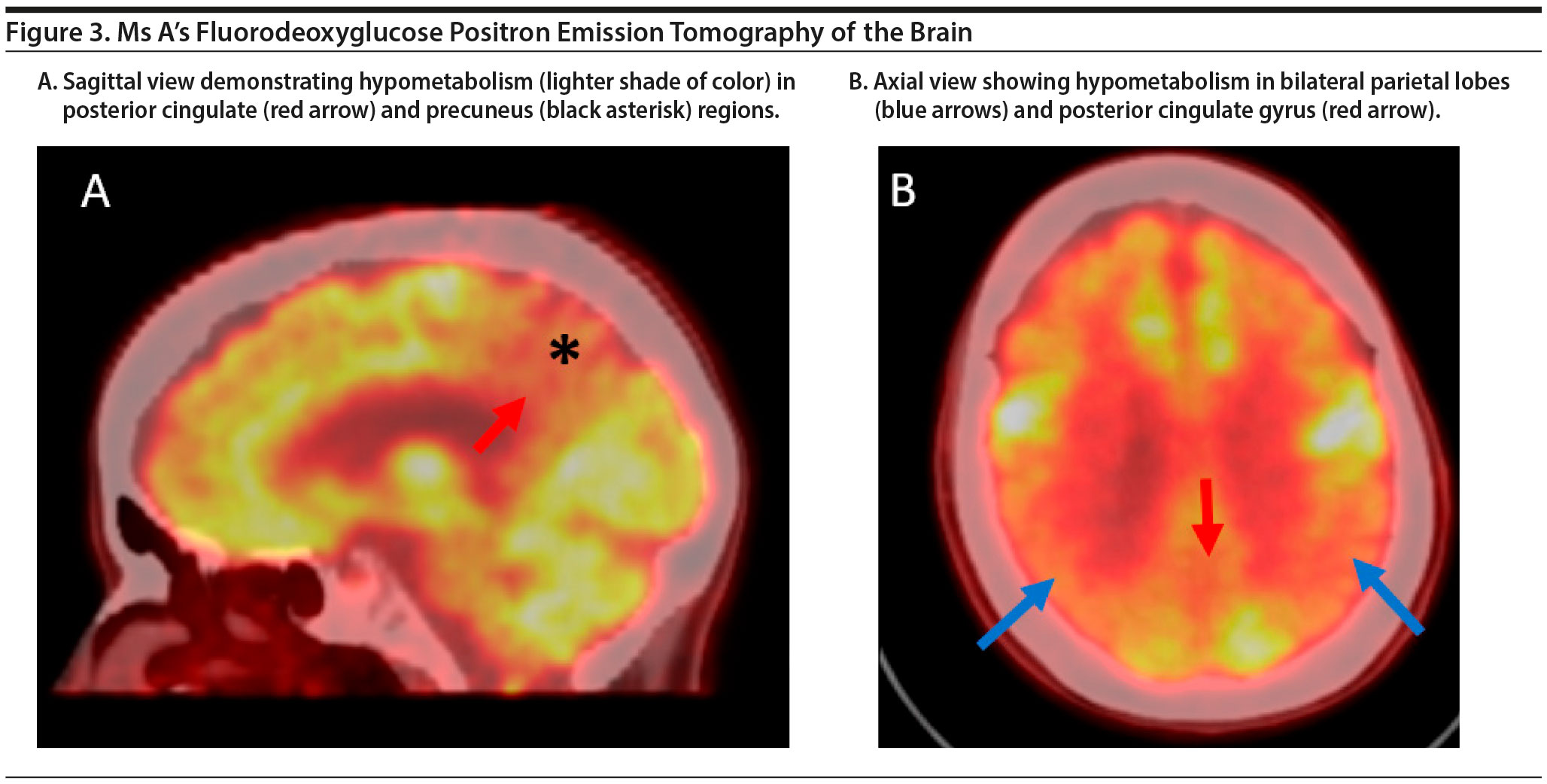

The treating physician decided to pursue FDG-PET imaging of the brain to evaluate a pattern of hypometabolism to aid in the differential diagnosis. Although there are 3 amyloid PET ligands (florbetapir, flutemetamol, and florbetaben) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, their costs are not currently covered by insurance plans. Genetic testing is expensive, and with no diagnosis, it is difficult to determine what genetic tests to order. CSF analysis allows evaluation for infectious and inflammatory processes. However, although safe, lumbar puncture is an invasive procedure, and Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers are currently the only clinically available biomarkers.

The FDG-PET scan of Ms A is shown in Figure 3. There is relatively symmetric abnormal decreased FDG uptake within the bilateral posterior temporal and parietal lobes involving the posterior cingulate gyri and precuneus and to a lesser degree the bilateral superior frontal lobes. This pattern of hypometabolism is characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. Therefore, given her age, Ms A was diagnosed with major neurocognitive disorder due to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

DISCUSSION

Prevalence of dementia is noted to increase progressively with increased age. One study (Lobo et al, 2000) showed 0.8% in the group aged 65 to 69 years and 28.5% in those aged 90 years and older. The corresponding percentages for Alzheimer’s disease (53.7% of cases) were 0.6% and 22.2%, respectively, and for vascular dementia (15.8% of cases) were 0.3% and 5.2%, respectively (Lobo et al, 2000). Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease is defined as onset of symptoms at age ≤ 65 years. The incidence of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia has been noted to be similar. One study (Mercy et al, 2008) reported 4.2 per 100,000 person-years for early-onset Alzheimer’s disease and 3.5 cases per 100,000 person-years in frontotemporal dementia in patients aged 45-64 years.

In the various neurodegenerative dementia syndromes, forgetfulness is often the most common complaint, although the etiology for the forgetfulness could be due to other cognitive domains besides memory such as attention or executive function. Typically, patients do not self-present but rather are brought in by family members or caretakers. Initial symptoms may be subtle but progressively worsen over the course of years until more severe symptoms such as difficultly managing finances or driving begin.

Neuropsychological testing has demonstrated effectiveness for evaluation and clinical monitoring of patients with mild cognitive impairment (Petersen et al, 2001). Early completion of neuropsychological testing is essential, as the initial pattern of cognitive impairment is often the most informative in suggesting a specific cause of dementia (Gurnani and Gavett, 2017). As degenerative dementia progresses, more cognitive domains are affected, leading to global impairment as was the case of Ms A. In addition, when the symptoms become severe, they are likely to interfere with the patient’s ability to participate and complete neuropsychological evaluations.

In addition, to characterize the degree and pattern of cognitive impairments, neuropsychological testing could aid in differentiating between psychological comorbidities and a dementia process. For example, one of Ms A’s neuropsychological evaluations raised issues regarding diminished effort. While this is concerning for a psychological contribution, it remains important to complete a full workup to evaluate for an underlying neurodegenerative process because the 2 could coexist. In the evaluation of Ms A, brain MRI and FGD-PET scans were abnormal and showed cerebral atrophy and hypometabolism suggestive of Alzheimer’s disease. While Ms A’s history of abuse and diminished effort may have contributed to her presentation, imaging findings demonstrated a comorbid neurologic process.

Ms A’s case is also notable due to the early age of presentation. The evaluation of early-onset dementia involves more complete and thorough testing for other contributing factors. While history is paramount for evaluation of all cognitive impairment, it is especially important to evaluate in early-onset dementia. Evaluation of the exact type of cognitive impairment, personality changes, time course, and family history of dementia is essential. Assessment for other underlying pathologies such as multiple sclerosis, underlying neoplasm, or other organ system dysfunctions is also vital (Harvey, 1979). This is accomplished by performing laboratory studies and brain imaging, and lumbar puncture should be considered if central nervous system autoimmune or infection etiologies are suspected (Knopman et al, 2001). Furthermore, CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease are clinically available. Despite this more thorough workup, diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s dementia is complicated by the many variations in presentation in comparison to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. More frequently in early-onset Alzheimer’s dementia, nonamnestic and focal phenotypes such as frontal/dysexecutive, visual (posterior cortical atrophy), or language (logopenic progressive aphasia) variants are present (Mendez, 2017). There is also an increase in the occurrence of depression compared to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (Rosness et al, 2010). Imaging findings are also varied and demonstrate a greater neocortical atrophy focused more in the parietal areas and less atrophy in the mesial temporal lobe and hippocampal formations when compared to findings in patients with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (Migliaccio et al, 2015). Clinical progression of disease is significant for a faster rate of decline with higher burden of neurotic plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and greater synapse loss. It is important to consider the age at presentation and to recognize that early-onset Alzheimer’s disease may not appear in the typical presentation that providers consider in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

FUNDING/SUPPORT

None.

DRUG NAMES

Acetaminophen/oxycodone (Percocet), gemfibrozil (Lopid).

DISCLOSURE OF OFF-LABEL USAGE

The authors have determined that, to the best of their knowledge, no investigational information about pharmaceutical agents that is outside US Food and Drug Administration-approved labeling has been presented in this article.

Financial Disclosure

Drs Tsai, Kaur, and Gopalakrishna have no personal affiliations or financial relationships with any commercial interest to disclose relative to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed are those of the authors, not of Banner Health or Physicians Postgraduate Press.

Clinical Points

- Initial dementia evaluation becomes more difficult as the disease duration increases because symptoms and signs become less specific.

- In cases of suspected psychogenic etiology or contribution, medical workup remains important to elucidate an underlying neurologic cause.

- Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease appears to be a distinct disease entity that has different clinical, neuropsychological, and imaging presentations from late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

REFERENCES

Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(4):325-373.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, et al. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269(18):2386-2391. PubMed CrossRef

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. PubMed CrossRef

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. PubMed CrossRef

Gurnani AS, Gavett BE. The differential effects of Alzheimer’s Disease and Lewy Body Pathology on cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2017;27(1):1-17. PubMed CrossRef

Harvey AM. Differential Diagnosis: the Interpretation of Clinical Evidence. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1979.

Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56(9):1143-1153. PubMed CrossRef

Lobo A, Launer LJ, Fratiglioni L, et al; Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Prevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: A collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurology. 2000;54(suppl 5):S4-S9. PubMed

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263-269. PubMed CrossRef

Mendez MF. Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Clin. 2017;35(2):263-281. PubMed CrossRef

Mercy L, Hodges JR, Dawson K, et al. Incidence of early-onset dementias in Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom. Neurology. 2008;71(19):1496-1499. PubMed CrossRef

Migliaccio R, Agosta F, Possin KL, et al. Mapping the Progression of atrophy in early- and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46(2):351-364. PubMed

Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, et al. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56(9):1133-1142. PubMed CrossRef

Rosness TA, Barca ML, Engedal K. Occurrence of depression and its correlates in early onset dementia patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(7):704-711. PubMed CrossRef

Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, et al. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69(24):2197-2204. PubMed CrossRef

Please sign in or purchase this PDF for $40.00.

Save

Cite