Abstract

Medical students have few opportunities to lead patient groups during their clinical year. During the psychiatry clerkship, they are group observers and do not have the skills to lead psychotherapy or treatment groups. This report describes a bingo group led by medical students on an inpatient psychiatry unit. The group provides leadership opportunities for students lacking advanced group training, enables student integration into the ward, and reduces stigma. Patients find it easier to engage and benefit from socialization and improved cognitive and ego functioning. The group also provides continuity of care when staffing changes. Clerkship directors are encouraged to consider such a program.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2024;26(1):23m03576

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

There is little in the education literature describing patient groups run by medical students. Medical students participate in groups1–3 but rarely lead them. Medical student–run groups usually comprise tutorials and didactic sessions or more recently stress management4 and grief groups5 for other students. There are numerous student-led health education initiatives and clinics,6 but these do not include medical student–led patient groups. This report describes a bingo group for psychiatry inpatients run by medical students. We are unaware of such a group described in the literature.

For 6 years, Albert Einstein College of Medicine (Bronx, New York) psychiatric clerkship students have co-led a weekly patient bingo group in a psychiatric state hospital training unit. Over the last year, observations regarding the benefits of this group were elicited from staff, psychiatry residents, and students by means of an open-ended series of questions. The survey was voluntary and not anonymous. Twelve of 21 students and 9 of 17 staff responded. Medical students report that the group increases empathy and decreases stigmatization. It fosters confidence, facilitates integration into the ward, and teaches group process. For some students, it encourages specialization in psychiatry. According to staff, the group provides patients with role models and aids in social learning and cognitive and ego functioning. On the training unit, there are frequent changes of staff and trainees. Students now leave after 4 weeks, and psychiatry residents leave after 4 months. The ongoing group enables the patients to develop an attachment, or transference, to the group that carries them through loss and change. It provides continuity of care.

OVERVIEW OF THE BINGO GROUP

The bingo group was introduced in the inpatient psychiatry ward in September 2017, and since then more than 80 students have co-led the group during the 4 or 6 weeks of their psychiatry clerkship. Approximately 15 patients attend the group each week. Most of these patients have been diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and range in age from 19 to 72 years. During the first week, a supervisor orients students to how the group is run and then passes leadership to them. The group is run like a traditional bingo group, with 2 cards per participant, and the medical students call out numbers from a machine. Patients keep track of their own cards and announce “bingo” when they win. Prizes include toiletries, fruit, and snacks.

WHAT THE GROUP PROVIDES PATIENTS

Easier Engagement

Psychotic disorders are associated with negative symptoms such as apathy and amotivation, with greater loneliness, increased social isolation,7 and comorbid social anxiety disorder.8 Many patients have endured childhoods filled with social, financial, and familial stress. Some have experienced abuse,9 resulting in posttraumatic stress disorder and manifesting in avoidance. These symptoms can present as common ward behaviors of fatigue, oversleeping, and television watching, which make it difficult to rouse a patient for most group sessions. In contrast, patients are eager to attend the bingo group. They describe it as “something of value” and “an entertaining distraction from the rest of day-to-day life” on the ward. It is a place to get to know the new medical students: “We like to make friends and get to know new people,” one patient observed, “I look forward to it. It helps our morale.” A psychiatry resident noted that “patients who fail to engage with other groups consistently attend the bingo group,” perhaps because it is less intimidating.

Social Skills and Improved Cognitive and Ego Functioning

Working with others and sharing is promoted by the group setup: all participants will eventually get prizes, and no one can win more prizes than another. Participants learn to negotiate with each other and with members of the staff. There is improved communication and problem-solving centered around the game. According to the ward attending, “The group allows patients to work individually and collectively toward a goal that gives them a sense of accomplishment.”

The group is a safe place to develop and practice social skills. Members are observed engaging cordially, sharing jokes, and clarifying numbers with each other. During the first group of each clerkship, the patients are the teachers, and the students are the learners. Patient members gain a sense of mastery competence10 by teaching the rules, setup, and process of the group and by providing leadership throughout the 4 to 6 weeks. This role provides a sense of responsibility and productivity, as well as an opportunity to exercise fairness. For example, when a member expresses frustration at not receiving a desired prize, a leader calms them and encourages sharing.

Other patients take the initiative by setting up chairs and boards. They help those with hearing problems or difficulty tracking the markers on the board. They model for those with poorer social and cognitive skills, instilling hope in their individual recoveries. These acts of altruism, integral to group therapy, can benefit self-esteem and contribute to self-efficacy.11 Similarly, the student co-leaders serve as role models by imparting their enthusiasm and optimism. Group members find it easier to learn from the students because they see medical students as learners like themselves.

The structure of the group promotes improvements in ego functioning.10 The need to focus on a bingo number, a marker, and a card brings the participant out of their psychotic revery or hallucinations into the real world, improving their reality testing. It helps frustration tolerance because the participants cannot receive more than 2 prizes. It strengthens impulse control when the members talk out their “prize frustration” rather than acting out. Playing the game requires concentration, attention, processing, and memory skills and encourages logical thinking. Patients call it “paying attention to the card.” A psychiatry resident described it as follows: “For patients suffering from negative symptoms of schizophrenia, the group is an accessible way to engage in cognitive rehabilitation.” Experiences from the group can be discussed in individual therapy, and ego functions are reinforced.

A Stable Routine and Continuity of Care

Patients are known to ask about the bingo group, as it has become part of their weekly routine. According to one psychiatry resident, her patients spoke regularly about the group and checked with her that the group was meeting. A student noted, “The bingo group provided patients with a regularly hosted event to look forward to, which wasn’t focused on therapy, which I think helped them to feel a sense of normalcy.” A staff member discussed the importance of ritual, “Most importantly and likely to be overlooked is the power of ritual, which is a way that people gather and focus energy.” An attending psychiatrist described the group as “a vital fixture on our unit with therapeutic benefits.” Patients and staff agree that the group improves morale.

In the general population, a stable daily routine is associated with well-being.12 For people with schizophrenia, this is even more important, as lack of a stable routine results in more severe symptoms.13 The stable routine provided by the bingo group coincides with continuity of care, a process whereby health care providers give relevant and uninterrupted care while assisting with transitions between different levels of care. The bingo group runs continuously despite the stress of ward disruptions, staffing changes, and new students each clerkship. While patients may forget individual students, they remember that every Thursday there is the bingo group—a composite of years of enjoyable relationships. Patients have developed a positive group transference. If a patient forms an attachment to a group that runs consistently, despite the frequent arrivals and departures of group leaders, the changes are less likely to trigger decompensation. Treatment interruption is one potential driver of relapse.14

WHAT THE GROUP PROVIDES STUDENTS

Integrating Into the Unit as Newcomers

The psychiatry ward can be an intimidating experience for students. Safety precautions, such as locked doors and mandatory self-defense training, reinforce students’ preconceptions about possible dangers. Students are the newest staff and may feel unsure of their role on the ward and anxious when approaching patients. The group is a welcoming committee for the students and an efficient way for the students to meet more than half the ward patients. The members greet the students on the first day to ask if they will be running the group. Patients quickly associate the students with the group, facilitating student acclimation. The bingo group enables a student to move beyond the traditional one-on-one alliance taught in medical school and to become a co-leader of a medical student–led group that is greater than its individual leaders and will outlast the students’ 4- to 6-week tenure. The students are quickly integrated into this ongoing group/institutional transference and are handed a premade student-patient alliance.

Such a group might help to avert student burnout. It is estimated that at least half of all medical students could be affected by burnout,15 and that burnout was intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic and the shift to virtual education. One multistate study16 assessed the effect of work conditions on medical students and reported that burnout in the clinical years was related to “clerkship organization and exposure to cynical residents.”p280 One protective factor is a positive learning and working environment.17

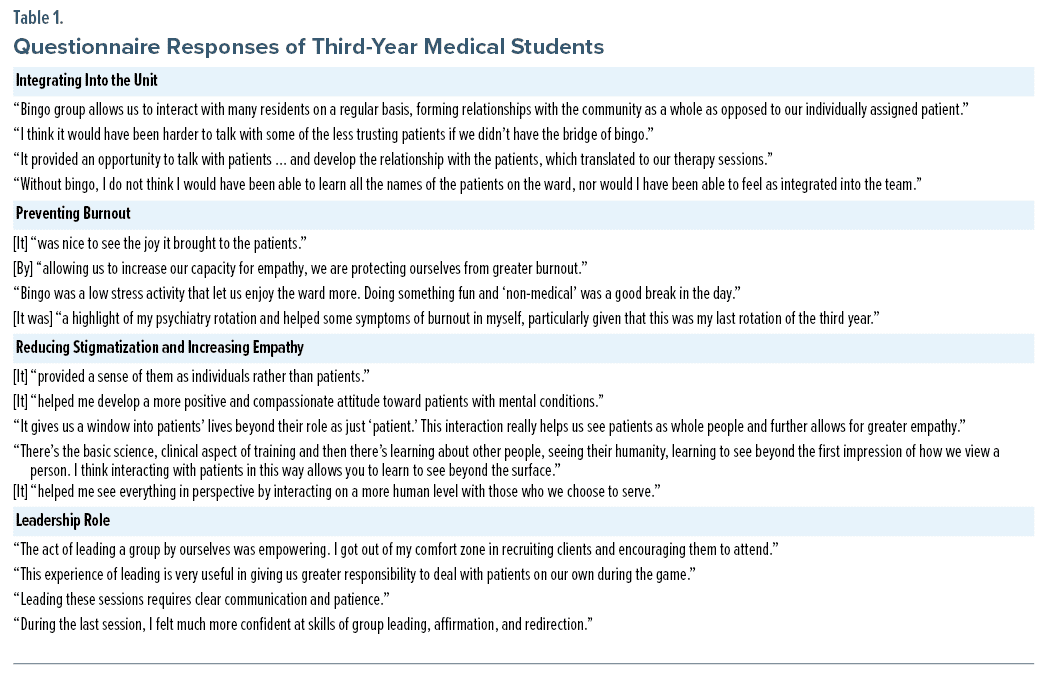

The bingo group fosters a positive environment. Students describe the group as “a fun experience” that helped them “enjoy the ward more.” In a demanding clerkship year, co-leadership of the group provides a less stressful role that leads to immediate rewards. One student called it “a unique opportunity to interact with patients totally unlike anything experienced in any other clerkship.” Another student wrote, “This simple, positive human interaction can be refreshing in a year of studying and being evaluated. Spending time with these patients in this happy environment helps to remind me of the reasons I pursued medicine in the first place.” Table 1 provides an overview of the students’ responses to the survey.

Reducing Stigmatization and Increasing Empathy

Direct patient contact can reduce stigma and improve empathy. Stigmatization occurs when a person and their attributes (social identity) do not conform to expectations or assumptions about what the individual before us ought to be. The person is “reduced in our minds from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one”p3 who is socially shunned.18 Empathy is defined as the ability to perceive and understand a patient’s feelings as if the clinician were experiencing them and to communicate that accurate understanding to the patient.19

Stigma and empathy are interdependent: empathy is negatively correlated with stigma or prejudice.20 While there is research indicating that empathy declines in medical school,21 there are educational interventions that can improve empathy. These interventions include patient narratives and communication skills training,22 as well as clinical exposure.23,24 According to the contact theory,24 direct contact with people with mental illness can improve attitudes and increase acceptance. Several studies25–27 have shown a modest improvement in students’ attitudes following the psychiatry clerkship. However, an inpatient clerkship—as opposed to a combined inpatient/outpatient clerkship—was less able to alter attitudes. This could be related to the students’ perception that inpatients are dangerous25 or engulfed by a “state of demoralization.”26

Groups such as the bingo group counter these negative perceptions. Because the ward runs many psychotherapeutic groups, the bingo group can deemphasize symptoms and illness and reveal another side of the individual—as someone who can give and share and enjoy. The bingo group humanizes the members, and the students come away with respect, moving beyond the categorization of patient to the person (see Table 1).

The Group Process

While the bingo group has the qualities of a skills development or support group rather than a traditional therapy group, it possesses some universal characteristics of group therapy, including here-and-now member-to-member interactions and intrinsic leadership roles. Therapeutic factors include altruism, whereby members “gain through giving,” modeling and imitative behavior, the imparting of direct advice, and group cohesiveness,11 which helped to counter the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The act of conducting co-therapy is an excellent avenue for training students, residents, and mental health professionals,11 as it introduces students to the group process. How does the group interact as a whole? How do the members interact with the leaders? Are there specific behaviors or concerns and themes that are displayed or verbalized in the context of the group (or game as relates to the bingo group, specifically). Are there some members who rise to leadership roles and others who require support and help with socialization? How do you lead with a co-therapist? Students hone their observational skills and gain an understanding of patients’ functioning and personalities. One student was able to share insights from the group in morning rounds and team meetings. Students were better able to predict the behavior of patients, keeping track of patients’ cognition or changes in mental state.

Learning About Psychiatry as a Potential Future Career

Much has been written about how to interest medical students in the specialty of psychiatry. The number of students entering psychiatry has increased since 2011, possibly due to a heightened interest in the social determinants of health.28 Pre-clerkship factors associated with the choice of psychiatry include sex, prior psychiatric work experience, and family or personal illness.29 A survey by Goldenberg et al30 indicated that providing an exemplary clerkship could increase the choice of psychiatry as a specialty. However, Farooq et al29 found that it was not the clerkship per se, but the degree of responsibility given to the students that increased their interest.

For reasons related to clerkship length, training, and experience, students can only observe the psychotherapy and forensic groups on the ward. The bingo group, however, gives them increased responsibility and a leadership role. One student described this as “empowering, stepping outside of my comfort zone” (see Table 1).

CONCLUSIONS

The bingo group, co-led by third-year medical students, is far richer and more productive than its name would indicate. It has advantages for patients, students, and the overall ward. For patients, the group facilitates group transference and continuity of care as trainees and staff change. It offers accessible engagement and a sense of routine and was key to overall morale on the ward during the era of COVID-19 isolation. For medical students, the group facilitates rapid integration into the ward, decreases stigmatization, and fosters empathy. It adds to the students’ role on the ward and gives them increased responsibility, combats burnout, and provides a gateway into psychiatry as a specialty.

Limitations to this review include low response rates from staff to the open-ended questions and lack of direct interviews with patients. In the future, an institutional review board–sanctioned research study would enable the distribution of questionnaires to group members. Other limitations include potential bias due to the lack of anonymity of student responses and the distribution of the questions at the end of the clerkship when students were concerned about grading. In addition, the state hospital ward is not typical of many inpatient psychiatric wards. Due to their forensic status, patients have a longer stay and this could further cohesion within the group. Over the past 5 years, the group has aged, and this could correlate with the success of the bingo group. Younger patients might benefit from a similar group with a different game—a virtual game or more skill-based game—during which they could work together more directly.

It is hoped that the positive impact of this group will encourage clerkship directors to integrate similar experiences into their programs. According to one clerkship student, “Having more groups that allow patients and providers to interact in this informal manner could go a long way to improving our outlook on patients.”

Article Information

Published Online: January 11, 2024. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.23m03576

© 2024 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: June 7, 2023; accepted September 11, 2023.

To Cite: Woesner ME, Cheung AM. Impact of a medical student–run bingo group on psychiatry inpatients and students. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2024;26(1):23m03576.

Corresponding Author: Mary E. Woesner, MD, Department of Psychiatry, 1st Floor Clinicians Suite, Adult Building, Bronx Psychiatric Center, 1500 Waters Place, Bronx, NY 10461 ([email protected]).

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Bronx Psychiatric Center, New York (Woesner); Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York (Woesner, Cheung).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Previous Presentation: Presented as a poster at the 2nd Annual Psychiatry Research Institute of Montefiore and Einstein (PRIME) Research Day; Bronx, New York; May 11, 2023.

CLINICAL POINTS

- Medical students rarely lead inpatient psychiatry groups during their clerkships.

- Co-leading an inpatient bingo group improves the clerkship experience for medical students and provides therapeutic benefits to patients.

- Clerkship directors and medical educators could include similar activities in their curriculum.

References (30)

- Neumann M, Elizur A. Group experience as a means of training medical students. J Med Educ. 1979;54(9):714–719. PubMed CrossRef

- Dashef SS, Espey WM, Lazarus JA. Time-limited sensitivity groups for medical students. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131(3):287–292. PubMed CrossRef

- McManus S, Killeen D, Hartnett Y, et al. Establishing and evaluating a Balint group for fourth-year medical students at an Irish university. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37(2):99–105. PubMed CrossRef

- Redwood SK, Pollak MH. Student-led stress management program for first-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(1):42–46. PubMed

- Waldner A. Medical Student Led Grief & Loss Support Group. E-Learning Modules; 2014:16.

- Schutte T, Tichelaar J, Dekker RS, et al. Learning in student-run clinics: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2015;49(3):249–263. PubMed CrossRef

- Michalska da Rocha B, Rhodes S, Vasilopoulou E, et al. Loneliness in psychosis: a meta-analytical review. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(1):114–125. PubMed CrossRef

- Roy MA, Demers MF, Achim AM. Social anxiety disorder in schizophrenia: a neglected, yet potentially important comorbidity. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2018;43(4):287–288. PubMed CrossRef

- Muenzenmaier K, Spei E, Gross DR. Complex posttraumatic stress disorder in men with serious mental illness: a reconceptualization. Am J Psychother. 2010;64(3):257–268. PubMed CrossRef

- Bellak L, Hurvich M, Gediman H. Ego Functions in Schizophrenics, Neurotics, and Normals. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1973.

- Yalom ID, Leszcz M. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy. 6th ed. New York: Basic Books; 2020.

- Bond MJ, Feather N. Some correlates of structure and purpose in the use of time. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55(2):321–329. CrossRef

- He-Yueya J, Buck B, Campbell A, et al. Assessing the relationship between routine and schizophrenia symptoms with passively sensed measures of behavioral stability. NPJ Schizophr. 2020;6(1):35. PubMed CrossRef

- Olivares JM, Sermon J, Hemels M, et al. Definitions and drivers of relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic literature review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):32. PubMed CrossRef

- IsHak W, Nikravesh R, Lederer S, et al. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review. Clin Teach. 2013;10(4):242–245. PubMed CrossRef

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Harper W, et al. The learning environment and medical student burnout: a multicenter study. Med Educ. 2009;43(3):274–282. PubMed CrossRef

- Mian A, Kim D, Chen D, et al. Medical student and resident burnout: a review of causes, effects, and prevention. J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2018;4:094.

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. NY: Simon and Schuster; 2009.

- Hersen M, Hasselt VB. Basic Interviewing: A Practical Guide for Counselors and Clinicians. Philadelphia, PA: Erlbaum; 1998.

- McFarland S. Authoritarianism, social dominance, and other roots of generalized prejudice. Polit Psychol. 2010;31(3):453–477. CrossRef

- Chen DC, Kirshenbaum DS, Yan J, et al. Characterizing changes in student empathy throughout medical school. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):305–311. PubMed CrossRef

- Batt-Rawden SA, Chisolm MS, Anton B, et al. Teaching empathy to medical students: an updated, systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1171–1177. PubMed CrossRef

- Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Med Educ. 2004;38(9):934–941. PubMed CrossRef

- Corrigan PW, Penn DL. Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. Am Psychol. 1999;54(9):765–776. PubMed CrossRef

- Lyons Z, Janca A. Impact of a psychiatry clerkship on stigma, attitudes towards psychiatry, and psychiatry as a career choice. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):34. PubMed CrossRef

- Petkari E, Masedo Gutiérrez AI, Xavier M, et al. The influence of clerkship on students’ stigma towards mental illness: a meta-analysis. Med Educ. 2018;52(7):694–704. PubMed CrossRef

- Holm-Petersen C, Vinge S, Hansen J, et al. The impact of contact with psychiatry on senior medical students’ attitudes toward psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116(4):308–311. PubMed CrossRef

- Moran M. Psychiatry match numbers increase for 11th straight year. Psychiatr News. 2022;57(5):appi.pn.2022.05.5.24. CrossRef

- Farooq K, Lydall GJ, Malik A, et al; ISOSCCIP Group. Why medical students choose psychiatry: a 20-country cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):12. PubMed CrossRef

- Goldenberg MN, Williams DK, Spollen JJ. Stability of and factors related to medical student specialty choice of psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(9):859–866. PubMed CrossRef

This PDF is free for all visitors!

Save

Cite