Abstract

Importance: Adolescence and young adulthood can be a period of immense change. Navigating this critical period of development can be particularly challenging, even for healthy individuals, given the immense cognitive, emotional, neurobiological, physical, and social changes taking place during this time. The additional burden of the core symptoms of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and associated functional impairments can further complicate this transitional period through to full adulthood.

Objectives and Data Source: In this review, we focus on the distinctive behavioral and neurobiological characteristics of adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with ADHD. We discuss the variety of contemporary challenges faced by these patients as they transition to full adult maturity. A comprehensive literature search of PubMed was performed on February 23, 2022. We searched for English language peer-reviewed articles published in the previous 10 years using primary search terms including “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,” “adolescent,” and “young adult.” Importantly, we provide various innovative and practical strategies and solutions to overcome the challenges faced by AYAs with ADHD, with the aim of improving the management of this unique patient population.

Relevance: This review is intended to support physicians less familiar with the management and treatment of AYAs with ADHD.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2024;26(4):24nr03718

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by symptoms of inattention and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity that interfere with functioning or development.1 Emotional dysregulation is often a prominent feature.2 Onset is common during preschool years or childhood,3 with prevalence ranging between 5.5% and 11% in children and adolescents and 2.8% and 4.4% in adults.4–7 ADHD is a highly heterogeneous disorder in terms of etiology, clinical profiles, long-term trajectories, neurobiological mechanisms, and psychiatric comorbidities.8 Full diagnostic criteria persist from childhood to adulthood in 50%–65% of cases,9,10 although more recent findings suggest that this figure may be as high as 90%.11

The normal transition from childhood to adulthood can be challenging, even for healthy individuals. Adolescence and young adulthood, spanning the period from 10 to 24 years of age,12 is a period of immense change, including the onset of puberty and unique cognitive, neurobiological, emotional, physical, and social developments.13 The additional burden of ADHD symptoms and associated functional impairments further complicates the transition through adolescence and young adulthood.

The challenges related to transition of patients with ADHD from child and adolescent to adult mental health services have been well documented. This review focuses on the unique characteristics of adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with ADHD and the challenges that they face, which together may act as barriers to optimal care. Drawing on our clinical experiences of implementing evidence-based guidelines, and feedback from our patients, we describe innovative strategies and solutions for improving the management of AYAs with ADHD.

METHODS

This narrative review is based on searches of the online literature (PubMed search conducted on February 23, 2022). We searched for English-language peer reviewed articles published in the previous 10 years. Primary search terms included “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,” “attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity,” “attention deficit and disruptive behavior disorders,” “ADHD,” “adolescent,” “adolescence,” and “young adult,” supplemented by and combined with secondary terms (eg, “comorbidity,” “risky behavior,” and “brain development”). Reference lists of identified articles were manually searched to identify additional articles of interest.

NEUROBIOLOGY OF BRAIN DEVELOPMENT

Brain Development in Adolescence and Young Adulthood

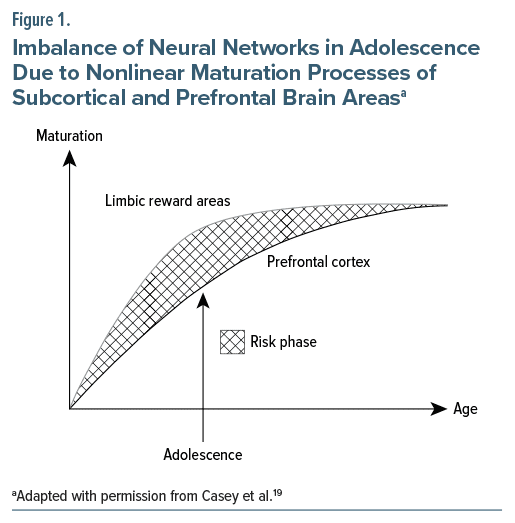

The brain is in an active state of development just prior to and throughout adolescence, with major anatomic reorganization and maturational events occurring,14 which help to prepare the brain for the challenges of adulthood. Brain maturation is an important part of the development of AYAs and may be influenced by numerous factors, including sex hormones, nutritional status, sleep patterns, heredity and environment, and use of pharmacotherapy.15 Basic features of brain maturation include pruning of rarely used synapses in grey matter and increases in myelination of axons in white matter, leading to a higher quality and speed of information transfer between brain regions.15–17 During adolescence, different regions of the brain grow and mature at different rates and at different times.18 Thus, the development and maturation of the prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive function, occurs mainly during adolescence and is complete by the time of full adulthood at 25 years of age,15 whereas subcortical brain areas, in particular the limbic system and the reward system, mature earlier, thereby creating an imbalance that may account for the typical behavior patterns observed during adolescence, including risk-taking (see Figure 1).16,19 Crucially, during adolescence, the developing brain is particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of environmental influences (eg, alcohol, nicotine, and cannabis) on neuronal plasticity.16,18 Other psychiatric conditions such as substance use disorders (SUDs) and mood disorders also tend to emerge during adolescence, and the risk of suicide is increased during this period.13,20

ADHD and Brain Development

A wealth of evidence indicates that the neurobiology of ADHD is multifactorial, involving structural and functional brain abnormalities and alterations in neurochemical signaling.21–29 Rather than specific abnormalities characteristic of ADHD, the structural and other differences identified in ADHD brains may be due to a delay in normal development. In a prospective magnetic resonance imaging study, children and adolescents with ADHD exhibited significant delays in cortical maturation versus those without ADHD.30 Delays were most prominent in prefrontal cortical regions, which are important for control of cognitive processes, including attention and motor planning.30 The maturation of dopaminergic neuronal pathways in specific brain regions also appears to be delayed in children and adolescents with ADHD.31

Abnormalities in brain development appear to occur in the first few months of life, before clinical manifestations of neurodevelopmental disorders become evident.32 Indeed, a systematic review of children later diagnosed with ADHD demonstrated that motor signs of ADHD that emerged during the first year of life appeared nonspecific; this limits their value in clinical screening.33 Collectively, evidence to date clearly demonstrates that ADHD is a brain disorder; this is an important message to convey to AYAs with ADHD and their parents to help reduce the associated stigma.21

BARRIERS TO THE MANAGEMENT OF ADHD IN ADOLESCENTS AND YOUNG ADULTS

ADHD follows a highly variable course throughout adolescence; while hyperactivity and impulsivity tend to decline, inattention can be more persistent.34 Academic performance35; relationships with parents36; quality of life37; self-esteem38; behavioral, emotional, and social functioning39; and peer relationships39 may all be adversely affected by ADHD during adolescence. A diagnosis of ADHD also reduces the life expectancy of young adults40 and increases the mortality rate.41

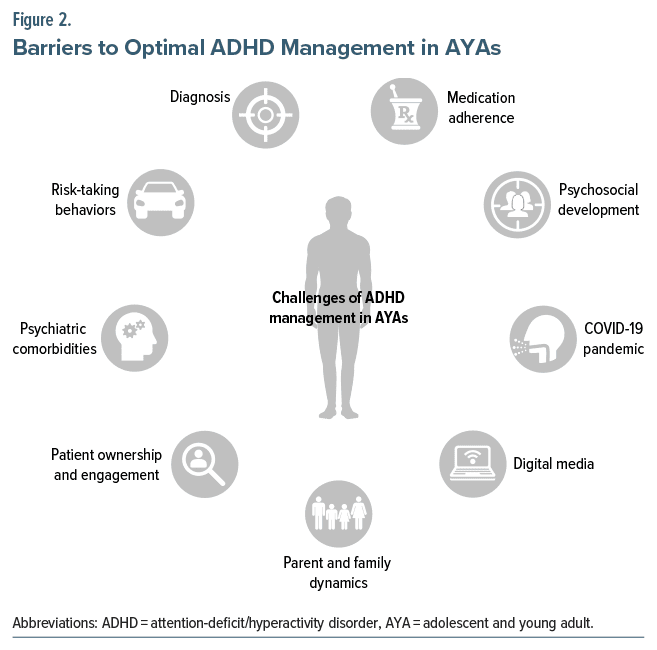

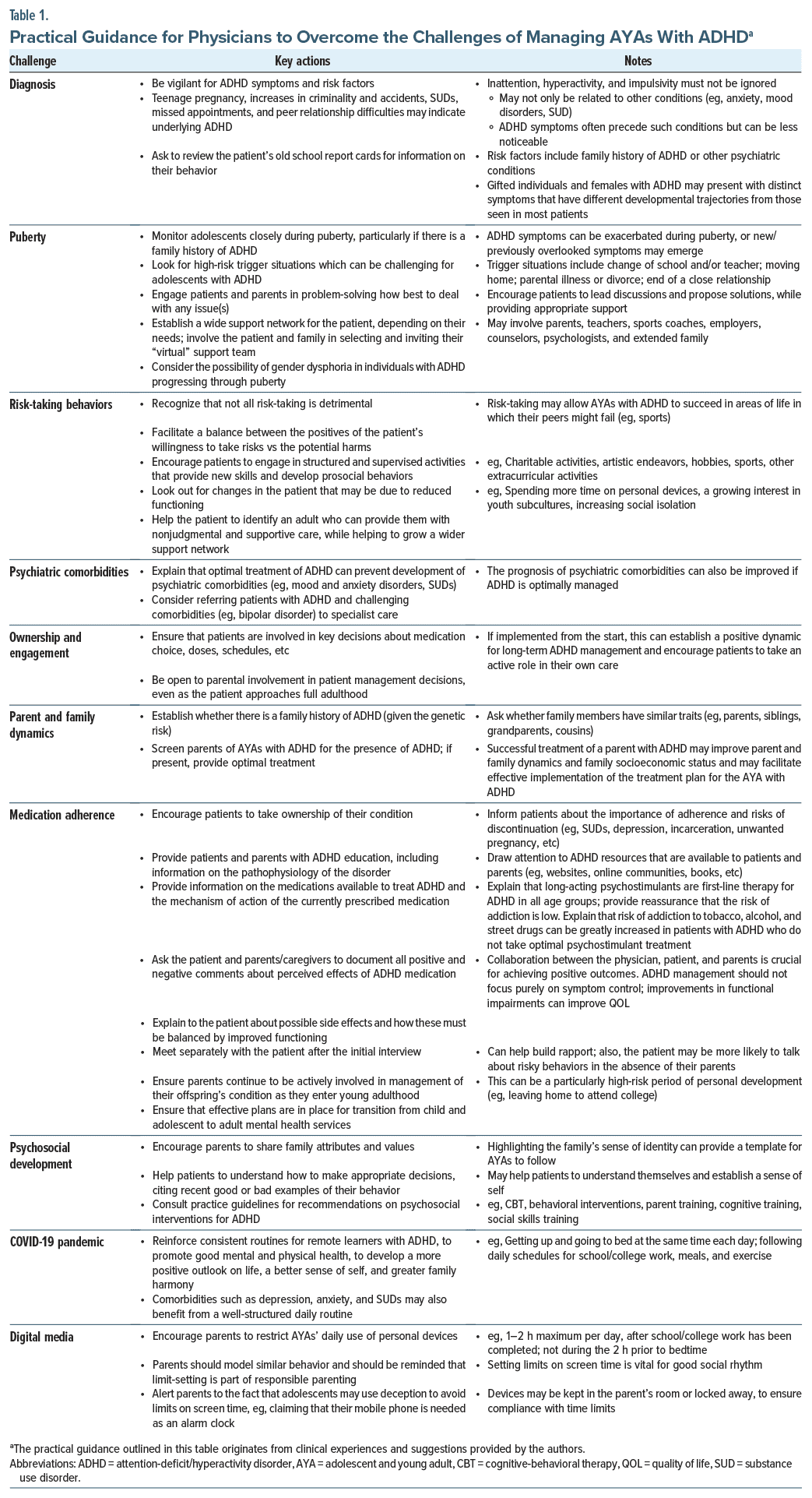

In AYAs, normal healthy behaviors are often difficult to distinguish from the subtle symptoms of ADHD. As a result, primary care providers must be vigilant for ADHD symptoms in this age group and should evaluate functional impairment to help differentiate ADHD from normal behaviors. As summarized in Figure 2, AYAs with ADHD face a wide variety of challenges while transitioning to full adulthood. Together with the unique characteristics of AYAs themselves, this means that it can be challenging to achieve optimal symptom control for these patients. Drawn from our own clinical experiences, Table 1 provides a number of innovative and practical strategies and solutions for overcoming the challenges that AYAs with ADHD often have to face, which are discussed in more detail below.

Diagnosis of Adolescent ADHD

When diagnosing patients with ADHD, clinicians should apply the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5).1,42 The definition of ADHD was broadened in the DSM-5.1,43 Firstly, the age of onset criterion changed from the onset of symptoms and impairments before the age of 7 years to the onset of symptoms before the age of 12 years.43,44 Secondly, the minimum number of symptoms required in the inattention and hyperactivity impulsivity domains for older adolescents and adults was reduced from 6 to 5.44 Functional impairments were only required to interfere with or reduce the quality of social, academic, or occupational functioning, rather than be clinically significant.44 Lastly, ADHD “subtypes” were renamed ADHD “presentations,”44 to recognize that ADHD symptoms are not stable traits and may change over time.

The diagnosis of ADHD remains a significant challenge in all age groups due to the wide variability in ADHD symptoms, the changes in ADHD symptoms with age, and the presence of comorbidities.42,45–47 Diagnosis of ADHD in AYAs requires a comprehensive assessment conducted in the primary care setting by a health care professional, with specialist referrals for more complex cases.42 Lack of awareness and knowledge of ADHD among health care professionals may contribute to misdiagnoses.46 Technological advances, such as machine learning–based predictive modeling, may facilitate diagnosis and help to minimize misdiagnoses.48–50

Puberty

The beginning of adolescence involves the onset of puberty.13 Sharp rises in sex hormones (estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone) during puberty can impact the development and maturation of the adolescent brain.15 Sex hormones directly influence myelinogenesis and remodeling of neurocircuitry in the adolescent brain15 and can have effects on the structure and connectivity of different brain regions.51 For example, the amygdala is involved in modulating and integrating emotional responses, is rich in sex hormone receptors, and undergoes substantial structural and functional changes during adolescence.52

Puberty can be a period of immense emotional turmoil due to the effects of changes in sex hormones. Consequently, puberty can be even more challenging and stressful for adolescents with ADHD, and in females symptoms can be exacerbated by hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle,53 in response to varying levels of sex hormones.54

Risk-Taking Behaviors

Typically, developing adolescents are prone to making impulsive and risky decisions, and this can be further exacerbated by ADHD.55 AYAs with ADHD are particularly susceptible to risk-taking behaviors, which may have a detrimental long-term impact,56 and such behaviors should be regarded as red flags for ADHD in this patient population. Adverse outcomes associated with high-risk behaviors include substance misuse (eg, cocaine and marijuana),57 smoking,58 having unprotected sex (associated with teenage pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections),59–61 gambling,62 dangerous driving,63 and criminality.64 AYAs with ADHD are also at increased risk of suicidal behavior,65 suicide attempts,66,67 and suicidal ideation.67

The main driving force behind risk-taking behavior in individuals with ADHD appears to be the perceived benefits of that behavior, rather than insensitivity to the risks involved.68 While risk-taking among AYAs is generally viewed negatively, particularly given the high mortality rate in 15–24 year olds,15 it is an important part of an individual’s development and can help to shape their future. Positive (socially acceptable) risks can have favorable outcomes, such as enrollment in a challenging course to learn a new skill, trying new hobbies, and willingness to build new friendships.55,69

The link between ADHD and risk-taking behavior in AYAs may involve sensation-seeking personality traits and deficits in executive functioning,70 but further research is needed to understand the neurobiological origins of the increase in this behavior in AYAs with ADHD. The extent of involvement of the 2 brain areas implicated in typical adolescent risk-taking behavior (ie, the subcortical and prefrontal control regions) is also still to be fully understood.16,19,55,71

Psychiatric Comorbidities

ADHD rarely exists in isolation and is commonly comorbid with other neurodevelopmental and mental health disorders throughout adolescence, including mood and anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, SUDs, oppositional defiant disorder, autism spectrum disorders, and tic disorders.72–75 Approximately 75% of children and adolescents with ADHD develop a comorbid psychiatric disorder76; this may increase the severity of ADHD symptoms and worsen functional impairment.77 Such comorbidities can also mask ADHD symptoms, which can complicate diagnosis75 and therapeutic interventions for ADHD.73 Indeed, symptoms of certain comorbid psychiatric disorders, such as bipolar disorder, can overlap with ADHD symptoms and represent a diagnostic challenge for the physician, and in these cases, referral to secondary care should be considered.42,78 For patients with ADHD and comorbidities, practice guidelines suggest that the diagnosis with highest impairment should be treated first.42 In AYAs, treatment of ADHD can be delayed and/or deprioritized when comorbid psychiatric conditions with higher impairment are present. Some mental health disorders (eg, suicidal depression) may be treated first, as they are acknowledged to be more impairing. However, ADHD is an eminently treatable condition, and effective treatments can minimize impairment.79 Therefore, ADHD should be treated as early as possible during adolescence, or preferably before. This approach should maximize the positive impact of treatment on long-term outcomes and reduce the risk of other psychiatric comorbidities.

Ownership and Engagement

In adolescence, individuals become increasingly independent from their caregivers in making decisions and taking responsibility for their actions.56,80 Adolescents with ADHD need to take responsibility for and ownership of their condition (eg, by adhering to prescribed medication).3 Some adolescents may fail to realize the significance of an ADHD diagnosis due to limited insight into their condition.56,81 Some health care providers may fail to communicate to patients that ADHD can persist into adulthood and become a life-long condition, with increased risk of comorbidities and significant negative consequences if not treated.77,82 This may perpetuate the tendency of AYAs with ADHD to lack ownership of their condition, leading to disengagement from treatment plans. However, as adolescents with ADHD mature and approach adulthood, they can become more engaged in managing their medication.83 Over time, they may be more accepting of the negative and positive aspects of their condition and more prepared to live with the “bad and the good” aspects of the disorder.84

Given the nature of symptoms experienced by AYAs with ADHD (eg, impulsivity and difficulty in processing and managing information), when they are asked to make decisions about treatment, support from their parents can be crucial. Ideally, patients, parents, and clinicians should all play an active role in ADHD management, taking joint ownership of the condition and sharing decision-making.85

Parent and Family Dynamics

As discussed, adolescence and young adulthood is typically a challenging period of life due to the rate and extent of physical, cognitive, and emotional changes. Parents and families can also be affected. Increased conflict, miscommunications, and misunderstandings are commonplace among families as individuals progress through adolescence and can be magnified by ADHD.86 Interpersonal problems are common among young adults with ADHD,87 which can negatively affect relationships between adolescents, parents, and siblings.88

A large community-based online study in 10 European countries demonstrated that caregivers (eg, parents or legal guardians) of children and adolescents with ADHD reported missed or altered work patterns, avoidance of social activities, increased worry and stress, and general strain on family life.89 A greater severity of ADHD symptoms and a higher number of comorbidities were significantly related to a greater burden on the caregivers.89

In another study, caregivers of children and adolescents with ADHD expressed concern that their relationship with their other offspring (without ADHD) could be negatively affected due to greater attention and focus on the sibling with ADHD.90 Conversely, adolescents with ADHD sometimes felt that their parents treated them differently from their siblings, which could lead to friction and arguments between siblings.90 Parents often become frustrated with their adolescents with ADHD and may withdraw from contact with them, which can magnify any relationship difficulties.86 Indeed, perceived parental rejection during early adolescence has been linked to persistence of ADHD symptoms in later adolescence,91 possibly due to the parents’ failure to provide emotional support. Given the key role of genetics in the etiology of ADHD,92 AYAs with ADHD frequently have parents who themselves have ADHD, which increases the tendency to have an impaired parenting style.93 In contrast, positive parenting during early adolescence may provide the emotional warmth that individuals with ADHD find supportive during this challenging period.91 Indeed, positive parenting at this time has been shown to initiate structural changes in areas of the adolescent brain that are key to reward processing and emotional regulation.94

Medication Adherence

Achieving adherence to ADHD medication is a well documented challenge in the management of adolescents with ADHD, despite evidence suggesting that continued treatment into adulthood improves long-term outcomes.85,95–97 A retrospective claims database analysis reported that more than 30% of patients diagnosed with ADHD and using ADHD pharmacotherapy at 17 years old had stopped taking medication by the age of 21 years.98 The likelihood of treatment disruptions or discontinuations increased as patients transitioned from adolescence to young adulthood, and they rarely reinitiated treatment.98 Consequences of poor adherence to ADHD medications can be significant and include reduced effectiveness of medications and increases in adverse events.79

There may be additional risks of nonadherence in certain patient groups, for example, in adolescent females with ADHD.61,99 Use of oral hormonal contraceptives can increase the risk of experiencing adverse effects such as depression, which may affect adherence to contraception and increase the risk of unplanned pregnancies.100 Providing information to female AYAs with ADHD on alternative contraceptive options that provide long-term protection without increasing the risk of depression, as well as discussing safe sex practices, may help prevent unplanned pregnancies.61,99,100

Adherence to medication is a complicated issue; adherence may be influenced by a variety of factors, some related to the ADHD medication itself, including the impact of adverse events, perceived effects on sense of self and personality, stigma of medication use, and inconvenience of taking regular medication.101 Clinician related factors can also influence adherence.102 Clinicians are responsible for educating patients and their families about ADHD, and making them fully aware of all aspects of treatment, with the aim of optimizing adherence.102 For example, clinicians should help the patient to understand the need to take their medications at the correct time and advise them how best to manage adverse events.102 Changes in life circumstances (eg, moving home) and personality traits may also impair medication adherence in AYAs with ADHD.96,103 Some AYAs may stop taking their medication because they regard ADHD as a childhood disorder and so assume that medication is no longer required as they grow older; some clinicians still retain this misunderstanding.96 Also, young people may regard the use of ADHD medication as a means of coping with school life and incorrectly assume that medication can be stopped once they have left the education system.96

Given adolescents’ desire for more control of their own destinies, they often decide themselves to stop taking their ADHD medication.101 However, as they may have limited insight into their condition,81 their decision will usually be scrutinized by their parents, whose beliefs about ADHD and attitudes toward treatment may also impact their child’s adherence behavior.85

Psychosocial Development

Adolescence marks a time of significant cognitive, physical, and sexual development, second only to infancy in the scale of the changes that occur. Psychosocial development also occurs, as individuals begin to develop an identity and sense of self and to establish their place in society.104 Adolescents begin to seek autonomy and independence from parents, and parental support becomes less important for their emotional adjustment.104,105 However, adolescents can become increasingly concerned about how they are perceived by other people, in particular their peers and family members.104,106

Adolescence can be an emotionally challenging time, even for healthy individuals who have a desire to establish their identity and sense of self and to feel like they “fit in.”106 The additional burden of ADHD symptoms complicates and may worsen the individual’s experience of this crucial step in their personal development. Indeed, an adolescent’s sense of self is thought to be distorted by ADHD.107

COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic was a challenging and stressful period. Individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders, such as ADHD, were particularly at risk due to the distressing impact of the pandemic.108,109 Government-imposed lockdowns and requirements for social distancing may have negatively impacted this vulnerable patient population.110 Compared with other adolescents, those with ADHD may have been at greater risk of increases in mental health symptoms and substance use during the pandemic.110 Problems with social isolation, difficulties engaging with online learning, lack of motivation, and boredom were also common among AYAs with ADHD.111

The global pandemic resulted in closure of schools, colleges, and universities and necessitated an extended period of online remote learning for millions of AYAs. Adolescents with ADHD experienced more difficulty with remote learning than their peers without ADHD112; this also increased their risk of depression and dropping out of school.111

Positive coping strategies may have been valuable for minimizing the impact of the increases in mental health problems and substance misuse among adolescents with ADHD during the pandemic.110 The concept of social rhythm is critical to the functioning and development of AYAs, especially those with ADHD. It relies on applying consistent routines to sleep, meals, and exercise to ensure that frequent social connections (eg, with family, peers, etc) are maintained. Implementing a regular and structured social rhythm throughout the pandemic and afterward may have been helpful to reduce the disruption caused by social isolation and frequent changes in schooling experienced by AYAs with ADHD.

Digital Media

Modern digital media has many different applications, including for social networking, streaming films or music, and videogaming.113 Digital media is widely used, easy to access at all times, and can provide users with instant high-intensity stimulation.113 Use of interactive digital media is ubiquitous in adolescents114; those with ADHD may be particularly vulnerable to the appeal of digital media, which can satisfy their need for peer and social connections and provides rapid feedback and immediate rewards via continual notifications and updates.113 Consequently, constant and uncontrolled use of digital media may be more likely to have negative consequences for these patients, such as academic failure, behavioral problems, social withdrawal, family conflict, and physical and mental health problems.114 Thus, adolescents with ADHD were found to be at increased risk of developing internet gaming disorder,115 described as “persistent and recurrent use of the internet to engage in games, often with other players, leading to clinically significant impairment or distress” (DSM-5).1 The COVID-19 pandemic also exacerbated problematic use of digital media in adolescents with ADHD, resulting in an increase in the severity of ADHD symptoms and associated difficulties (eg, lower motivation to learn).116

TREATMENT OF ADOLESCENT AND YOUNG ADULT ADHD

Given the personal, societal, and economic burden of untreated ADHD, there is a crucial need to accurately identify and treat ADHD in AYAs.117–121 Clinical practice guidelines recommend a multimodal and multidisciplinary treatment approach tailored to patients’ individual needs.42,122 Pharmacotherapy and psychosocial interventions, including psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, social skills training, parent management training, and ADHD coaching (by an accredited coach), may all be included in individualized multimodal therapeutic regimens.42,119 School-based interventions also have an important role to play in the multimodal treatment approach,42 including individualized education plans that provide special accommodations and modifications to meet the unique needs of individuals with ADHD and help them to fulfil their potential in the classroom.42,123 Several factors should be considered before deciding on appropriate treatment approaches; these may include severity of ADHD symptoms and impairments, levels of patient discomfort, impacts of psychiatric comorbidities, and global psychosocial functioning.79,124 Clinicians should involve the patient, parents, and any other caregivers (eg, teachers) in a collaborative treatment decision-making process to determine the specific needs of patients and their families.122,124

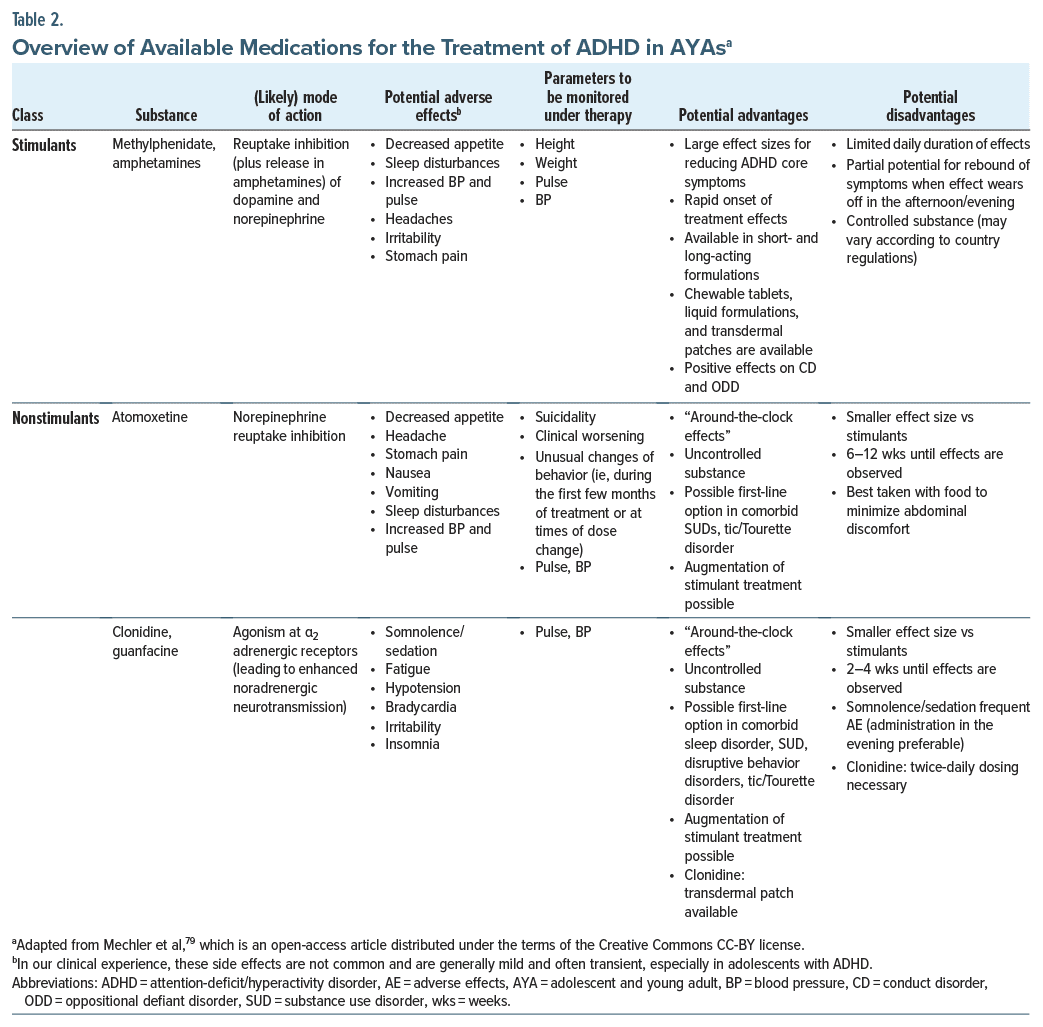

Pharmacotherapy comprises one part of a multimodal treatment plan.79 Table 2 provides an overview of medications approved for the treatment of AYAs with ADHD; these include psychostimulants such as methylphenidate (eg, osmotic release oral system methylphenidate hydrochloride), amphetamines (eg, lisdexamfetamine), and nonstimulants (eg, atomoxetine, clonidine, and guanfacine).42,79,122,124 Psychostimulants are available in short-acting and also long-acting formulations (adherence to the latter appears to be superior, most likely due to the convenience of once-daily dosing).125,126 Extended-release formulations of nonstimulants such as guanfacine also offer once-daily dosing.79 For adolescents with ADHD, psychostimulants are generally recommended as first line therapy and nonstimulants as second-line therapy.42,122 However, this depends on the approval status of the medications in specific countries and/or regions.79

Pharmacotherapy has been proven to be efficacious for the treatment of ADHD in adolescents.120,127 In general, the efficacy of psychostimulants has been shown to be greater than that of nonstimulants in adolescents with ADHD (the effect size is almost 1.0 for stimulants vs 0.6 for nonstimulants),128 and compared with nonstimulants, long-acting psychostimulants may provide greater improvements in ADHD symptoms and overall functioning.128,129 Psychostimulants have been reported to reduce structural and functional abnormalities in the brains of individuals with ADHD130 and are proposed to “normalize” the ADHD brain.131 The repair of structural and functional brain abnormalities may underpin the beneficial clinical effects of this class of ADHD medication.130

Reports of the effects of psychosocial treatments on ADHD symptoms in adolescents are inconsistent,127 but they appear effective for functional impairments such as poor academic and organizational skills.127 A combination of pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions should therefore improve the core symptoms of ADHD as well as reduce functional impairments and thereby improve quality of life.42 The benefits of psychosocial interventions may also be enhanced by ADHD medication, which may allow patients to focus more effectively.42

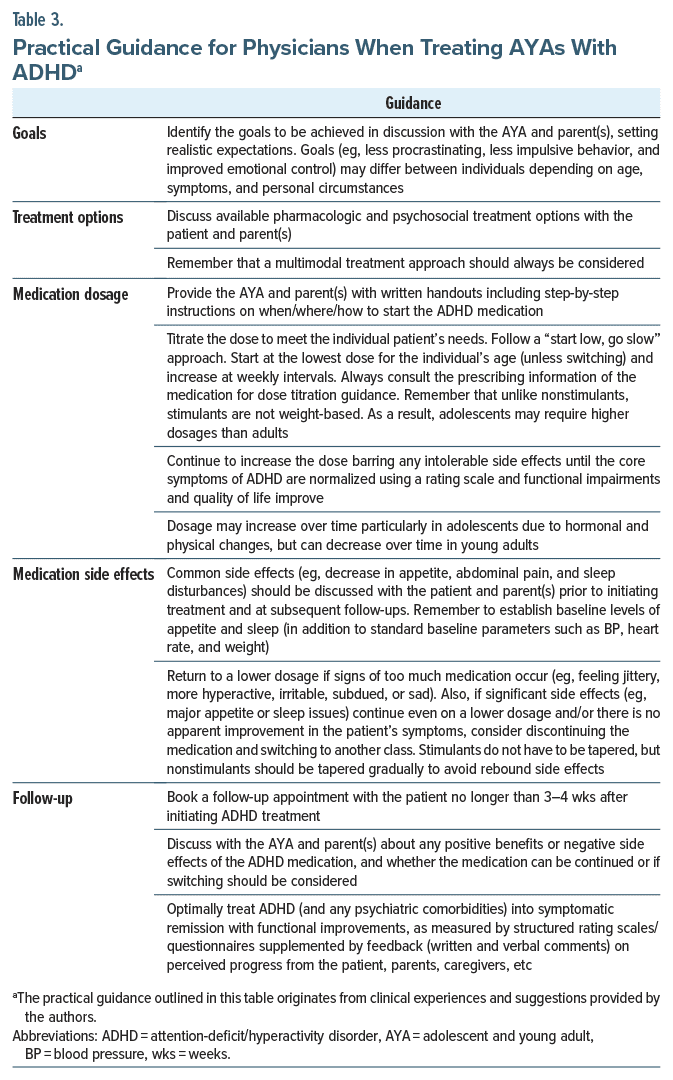

Optimal management of AYAs with ADHD may be time-consuming for physicians,3 but they should be prepared to proactively follow up with the patient to provide ongoing support, monitor medication use, and reinforce the importance of medication adherence. Factoring in the perspectives and feedback from across stakeholder groups (eg, patients, parents, and caregivers) is another important responsibility of the physician that helps shape the ADHD treatment plan. Setting realistic expectations of the treatment plan with all stakeholders from the outset (eg, what ADHD medications can and cannot achieve) and ensuring treatment goals are tailored for each patient can help to achieve positive outcomes and minimize adverse events. Based on our own clinical experience, Table 3 provides hints and tips for physicians treating AYAs with ADHD (please refer to evidence based guidelines, specific product monographs, and prescribing information for comprehensive guidance).

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Adolescence is a period of substantial cognitive, neurobiological, and social development, which prepares individuals for the challenges of adulthood.13 The rapid development of brain structure and function during adolescence, plus the simultaneous increase in cognitive ability, is referred to as a “critical period” of development.13

Beginning at the onset of puberty, this period is thought to be triggered by various factors, including the development of the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system.13 This may provide the necessary neurochemical and behavioral impetus to initiate the critical period of neurodevelopment in adolescence.13 The interaction of experiences and neurobiological factors (eg, development of excitatory and inhibitory neurocircuitry; changes in expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor) during the critical period may help to shape the normal development of the adolescent brain and permanently change behavior.13 The critical period is brought to a close by “braking factors” (eg, creation of perineuronal nets on neuronal cell bodies; increase in axonal myelination) that restrict further neuronal changes and stabilize neuronal circuitry, in preparation for the transition of the adolescent into adulthood.13

The increase in neuronal plasticity that occurs during adolescence may render the brain more vulnerable to psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders, adverse experiences (eg, trauma), and other pathogenic insults, all of which could lead to abnormal development of the adolescent brain and detrimental long-term outcomes.13,18 Nevertheless, the neuronal plasticity underlying the critical period of adolescence also offers a window of therapeutic opportunity for appropriate interventions to “normalize” the abnormal neurodevelopmental trajectory and positively impact or correct long-term outcomes.13 The treatment of ADHD in AYAs should therefore be prioritized, and unnecessary delays should be avoided, given that adolescence is a time when the adaptive neurobiological mechanisms of the adolescent brain may be at their most responsive to therapeutic interventions for ADHD.

The early months of postnatal life are also a critical period of brain development, during which neuronal plasticity is prominent.132 Potentially, therapeutic interventions during the earliest months of life could therefore have beneficial effects on the neurodevelopmental trajectories of people at risk of neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD.32 For this to become a realistic proposition, at-risk individuals would need to be identified as early as possible, either prenatally or in early infancy.32 Currently, no biomarkers can reliably identify and facilitate the diagnosis of individuals with ADHD.124,133 Should such a biomarker be discovered, this would allow screening (at birth) of the offspring of parents with ADHD and the possibility of providing prophylactic treatment, long before ADHD symptoms usually emerge.

In summary, the burden of ADHD and associated functional impairments can magnify the difficulties encountered during the transitional period of adolescence and young adulthood. AYAs with ADHD are faced with an array of challenges that can negatively impact the management of such patients. With regard to what can be achieved by ADHD management approaches, there are often major differences between the findings reported in clinical trial settings and observations of real-life outcomes from clinical practice.

Based on our combined clinical experience, we have provided practical hints and tips relating to ADHD diagnosis, puberty, risk-taking behaviors, psychiatric comorbidities, ownership and engagement, parent and family dynamics, medication adherence, psychosocial development, the COVID-19 pandemic, and digital media. By utilizing such strategies and solutions, the management of AYAs with ADHD may become more straightforward and achievable. Given the burden of untreated ADHD and the impact of psychiatric comorbidities, it is imperative that the management of ADHD in AYAs be prioritized.

Article Information

Published Online: August 6, 2024. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.24nr03718

© 2024 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: February 8, 2024; accepted April 5, 2024.

To Cite: Janzen T, Chang S, Farrelly G. Management of adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: unique challenges, innovative solutions. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2024;26(4):24nr03718.

Author Affiliations: Parkwood Institute, London, ON, Canada (Janzen); Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada (Chang); Departments of Pediatrics and Psychiatry, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada (Farrelly).

Relevant Financial Relationships: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Dr Janzen has received honoraria as a speaker and has been a member of advisory boards for Abbvie, Bausch Health, Eisai, Elvium Life Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Purdue Pharma, and Takeda. Dr Chang has received honoraria as a speaker and has been a member of advisory boards for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Elvium Life Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Purdue Pharma, and Takeda. He has also been a member of advisory boards for Allergan. He has been in receipt of grants from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Purdue Pharma, and Takeda. He is a faculty member of CanREACH and REACH, and he is an advisor/consultant to the Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA) on a Canadian ADHD and substance use project. Dr Farrelly has received honoraria as a speaker and has been a member of advisory boards for Elvium Life Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda. She serves on the advisory board and scientific conference committee of the CADDRA, and she is a faculty member of CanREACH.

Corresponding Author: Tom Janzen, MD, MCFP, 90 Parkwood Institute, 550 Wellington Rd, London, ON, N6C 0A7, Canada ([email protected]).

Funding/Support: The literature review and medical writing support were funded by Takeda Canada Inc., Canada. The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this manuscript.

Role of the Sponsor: Takeda Canada Inc. was not involved in the design of the literature search, analysis of the results, or writing of this manuscript. Employees at Takeda Canada Inc. reviewed the manuscript during development; however, the final approval and decision to submit the manuscript were the sole responsibility of the authors.

Acknowledgments: Medical writing support for the development of this manuscript, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Chris Cammack, PhD, of Ashfield MedComms, an Inizio Company, funded by Takeda Canada Inc., and complied with the Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines (DeTora LM, Toroser D, Sykes A, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:1298–1304).

ORCID: Tom Janzen: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9256-7781; Samuel Chang: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8712-8693; Geraldine Farrelly: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2463-5652

Clinical Points

- Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) possess distinctive behavioral and neurobiological characteristics, and these individuals face a range of unique challenges that may have an impact on optimal management as they transition to full adulthood.

- When managing AYAs, physicians should view risk-taking behaviors as a red flag for possible ADHD. Evidence continues to accumulate for the positive impact of the early detection and treatment of ADHD, as it can significantly reduce the risk of psychiatric comorbidities and materially change the trajectory of life for this patient population.

References (133)

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed;2013. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Faraone SV, Rostain AL, Blader J, et al. Practitioner Review: emotional dysregulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder – implications for clinical recognition and intervention. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(2):133–150. PubMed CrossRef

- Buitelaar JK. Optimising treatment strategies for ADHD in adolescence to minimise ‘lost in transition’ to adulthood. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26(5):448–452. PubMed CrossRef

- Fayyad J, Sampson NA, Hwang I, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of DSM-IV adult ADHD in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017;9(1):47–65. PubMed CrossRef

- Erskine HE, Baxter AJ, Patton G, et al. The global coverage of prevalence data for mental disorders in children and adolescents. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26(4):395–402. PubMed CrossRef

- Vande Voort JL, He JP, Jameson ND, et al. Impact of the DSM-5 attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder age-of-onset criterion in the US adolescent population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(7):736–744. PubMed CrossRef

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–723. PubMed CrossRef

- Luo Y, Weibman D, Halperin JM, et al. A review of heterogeneity in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13:42. PubMed

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med. 2006;36(2):159–165. PubMed CrossRef

- Lara C, Fayyad J, de Graaf R, et al. Childhood predictors of adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey initiative. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(1):46–54. PubMed

- Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(2):142–151. PubMed CrossRef

- Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, et al. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(3):223–228. PubMed CrossRef

- Larsen B, Luna B. Adolescence as a neurobiological critical period for the development of higher-order cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;94:179–195. PubMed CrossRef

- Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(10):861–863. PubMed CrossRef

- Arain M, Haque M, Johal L, et al. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:449–461. PubMed CrossRef

- Konrad K, Firk C, Uhlhaas PJ. Brain development during adolescence: neuroscientific insights into this developmental period. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110(25):425–431. PubMed CrossRef

- Johnson SB, Blum RW, Giedd JN. Adolescent maturity and the brain: the promise and pitfalls of neuroscience research in adolescent health policy. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(3):216–221. PubMed

- Dow-Edwards D, MacMaster FP, Peterson BS, et al. Experience during adolescence shapes brain development: from synapses and networks to normal and pathological behavior. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2019;76:106834. PubMed CrossRef

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA. The adolescent brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:111–126. PubMed CrossRef

- Bilsen J. Suicide and youth: risk factors. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:540. PubMed CrossRef

- Hoogman M, Bralten J, Hibar DP, et al. Subcortical brain volume differences in participants with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: a cross-sectional mega-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(4):310–319. PubMed CrossRef

- Greven CU, Bralten J, Mennes M, et al. Developmentally stable whole-brain volume reductions and developmentally sensitive caudate and putamen volume alterations in those with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and their unaffected siblings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(5):490–499. PubMed CrossRef

- Proal E, Reiss PT, Klein RG, et al. Brain gray matter deficits at 33-year follow-up in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder established in childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(11):1122–1134. PubMed CrossRef

- Shaw P, Lerch J, Greenstein D, et al. Longitudinal mapping of cortical thickness and clinical outcome in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):540–549. PubMed CrossRef

- Zhang-James Y, Helminen EC, Liu J, et al. Evidence for similar structural brain anomalies in youth and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a machine learning analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):82. PubMed

- Cortese S, Kelly C, Chabernaud C, et al. Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: a meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(10):1038–1055. PubMed CrossRef

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Newcorn J, et al. Depressed dopamine activity in caudate and preliminary evidence of limbic involvement in adults with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(8):932–940. PubMed CrossRef

- Economidou D, Theobald DE, Robbins TW, et al. Norepinephrine and dopamine modulate impulsivity on the five-choice serial reaction time task through opponent actions in the shell and core sub-regions of the nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(9):2057–2066. PubMed CrossRef

- Maltezos S, Horder J, Coghlan S, et al. Glutamate/glutamine and neuronal integrity in adults with ADHD: a proton MRS study. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4(3):e373. PubMed CrossRef

- Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19649–19654. PubMed CrossRef

- Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Functional connectivity of substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area: maturation during adolescence and effects of ADHD. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(4):935–944. PubMed CrossRef

- Finlay-Jones A, Varcin K, Leonard H, et al. Very early identification and intervention for infants at risk of neurodevelopmental disorders: a transdiagnostic approach. Child Development Perspect. 2019;13(2):97–103.

- Athanasiadou A, Buitelaar JK, Brovedani P, et al. Early motor signs of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29(7):903–916. PubMed

- Shaw P, Sudre G. Adolescent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: understanding teenage symptom trajectories. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89(2):152–161. PubMed CrossRef

- Birchwood J, Daley D. Brief report: the impact of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms on academic performance in an adolescent community sample. J Adolesc. 2012;35(1):225–231. PubMed CrossRef

- Garcia AM, Medina D, Sibley MH. Conflict between parents and adolescents with ADHD: situational triggers and the role of comorbidity. J Child Fam Stud. 2019;28(12):3338–3345.

- Lee YC, Yang HJ, Chen VC, et al. Meta-analysis of quality of life in children and adolescents with ADHD: by both parent proxy-report and child self-report using PedsQLTM. Res Dev Disabil. 2016;51–52:160–172. PubMed CrossRef

- Mazzone L, Postorino V, Reale L, et al. Self-esteem evaluation in children and adolescents suffering from ADHD. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2013;9:96–102. PubMed CrossRef

- Strine TW, Lesesne CA, Okoro CA, et al. Emotional and behavioral difficulties and impairments in everyday functioning among children with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A52. PubMed

- Barkley RA, Fischer M. Hyperactive child syndrome and estimated life expectancy at young adult follow-up: the role of ADHD persistence and other potential predictors. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(9):907–923. PubMed CrossRef

- Dalsgaard S, Østergaard SD, Leckman JF, et al. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190–2196. PubMed CrossRef

- Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance: Canadian ADHD Practice Guidelines, 4.1 Edition, CADDRA, 2020. Accessed 10 July, 2023. https://adhdlearn.caddra.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2022/08/Canadian-ADHD-Practice-Guidelines-4.1-January-6-2021.pdf

- Sanders S, Thomas R, Glasziou P, et al. A review of changes to the attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder age of onset criterion using the checklist for modifying disease definitions. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):357. PubMed

- Epstein JN, Loren REA. Changes in the definition of ADHD in DSM-5: subtle but important. Neuropsychiatry (London). 2013;3(5):455–458. PubMed CrossRef

- Katzman MA, Bilkey TS, Chokka PR, et al. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):302. PubMed

- Kooij SJJ, Bejerot S, Blackwell A, et al. European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: the European Network Adult ADHD. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:67. PubMed

- Silk TJ, Malpas CB, Beare R, et al. A network analysis approach to ADHD symptoms: more than the sum of its parts. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0211053. PubMed CrossRef

- Ghasemi E, Ebrahimi M, Ebrahimie E. Machine learning models effectively distinguish attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using event-related potentials. Cogn Neurodyn. 2022;16:1335–1349. PubMed CrossRef

- Chen T, Antoniou G, Adamou M, et al. Automatic diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder using machine learning. Appl Artif Intell. 2021;35(9):657–669.

- Rashid B, Calhoun V. Towards a brain-based predictome of mental illness. Hum Brain Mapp. 2020;41(12):3468–3535. PubMed CrossRef

- Peper JS, van den Heuvel MP, Mandl RCW, et al. Sex steroids and connectivity in the human brain: a review of neuroimaging studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(8):1101–1113. PubMed CrossRef

- Scherf KS, Smyth JM, Delgado MR. The amygdala: an agent of change in adolescent neural networks. Horm Behav. 2013;64(2):298–313. PubMed CrossRef

- Young S, Adamo N, Ásgeirsdóttir BB, et al. Females with ADHD: an expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in girls and women. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):404. PubMed

- Roberts B, Eisenlohr-Moul T, Martel MM. Reproductive steroids and ADHD symptoms across the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;88:105–114. PubMed CrossRef

- Dekkers TJ, de Water E, Scheres A. Impulsive and risky decision-making in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): the need for a developmental perspective. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;44:330–336. PubMed CrossRef

- Brahmbhatt K, Hilty DM, Hah M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder during adolescence in the primary care setting: a concise review. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(2):135–143. PubMed CrossRef

- Lee SS, Humphreys KL, Flory K, et al. Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/ dependence: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(3):328–341. PubMed CrossRef

- Mitchell JT, Howard AL, Belendiuk KA, et al. Cigarette smoking progression among young adults diagnosed with ADHD in childhood: a 16-year longitudinal study of children with and without ADHD. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(5):638–647. PubMed CrossRef

- Flory K, Molina BSG, Pelham WE Jr., et al. Childhood ADHD predicts risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35(4):571–577. PubMed CrossRef

- Chen MH, Hsu JW, Huang KL, et al. Sexually transmitted infection among adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(1):48–53. PubMed

- Skoglund C, Kopp Kallner H, Skalkidou A, et al. Association of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder with teenage birth among women and girls in Sweden. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912463. PubMed CrossRef

- Faregh N, Derevensky J. Gambling behavior among adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Gambl Stud. 2011;27(2):243–256. PubMed CrossRef

- Curry AE, Metzger KB, Pfeiffer MR, et al. Motor vehicle crash risk among adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):756–763. PubMed CrossRef

- Mohr-Jensen C, Müller Bisgaard C, Boldsen SK, et al. Attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in childhood and adolescence and the risk of crime in young adulthood in a Danish nationwide study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(4):443–452. PubMed CrossRef

- Garas P, Balazs J. Long-term suicide risk of children and adolescents with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder-a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:557909. PubMed CrossRef

- Sultan RS, Liu SM, Hacker KA, et al. Adolescents with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: adverse behaviors and comorbidity. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(2):284–291. PubMed CrossRef

- Babinski DE, Neely KA, Ba DM, et al. Depression and suicidal behavior in young adult men and women with ADHD: evidence from claims data. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(6):19m13130. PubMed CrossRef

- Shoham R, Sonuga-Barke E, Yaniv I, et al. What drives risky behavior in ADHD: insensitivity to its risk or fascination with its potential benefits? J Atten Disord. 2021;25(14):1988–2002. PubMed CrossRef

- Duell N, Steinberg L. Positive risk taking in adolescence. Child Dev Perspect. 2019;13(1):48–52. PubMed CrossRef

- Pollak Y, Dekkers TJ, Shoham R, et al. Risk-taking behavior in attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a review of potential underlying mechanisms and of interventions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(5):33. PubMed

- Shulman EP, Smith AR, Silva K, et al. The dual systems model: review, reappraisal, and reaffirmation. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2016;17:103–117. PubMed CrossRef

- Gau SSF, Ni HC, Shang CY, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity among children and adolescents with and without persistent attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(2):135–143. PubMed CrossRef

- Reale L, Bartoli B, Cartabia M, et al. Comorbidity prevalence and treatment outcome in children and adolescents with ADHD. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(12):1443–1457. PubMed CrossRef

- Friesen K, Markowsky A. The diagnosis and management of anxiety in adolescents with comorbid ADHD. J Nurse Pract. 2021;17(1):65–69.

- Antoniou E, Rigas N, Orovou E, et al. ADHD and the importance of comorbid disorders in the psychosocial development of children and adolescents. J Biosci Med. 2021;9(4):1–13.

- Banaschewski T, Becker K, Döpfner M, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(9):149–159. PubMed CrossRef

- Bélanger SA, Andrews D, Gray C, et al. ADHD in children and youth: Part 1- Etiology, diagnosis, and comorbidity. Paediatr Child Health. 2018;23(7):447–453. PubMed

- Miller S, Chang KD, Ketter TA. Bipolar disorder and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder comorbidity in children and adolescents: evidence-based approach to diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):628–629. PubMed CrossRef

- Mechler K, Banaschewski T, Hohmann S, et al. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment options for ADHD in children and adolescents. Pharmacol Ther. 2022;230:107940. PubMed CrossRef

- Young S, Amarasinghe JM. Practitioner review: non-pharmacological treatments for ADHD: a lifespan approach. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(2):116–133. PubMed

- Robb A, Findling RL. Challenges in the transition of care for adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Postgrad Med. 2013;125(4):131–140. PubMed CrossRef

- Price A, Newlove-Delgado T, Eke H, et al. In transition with ADHD: the role of information, in facilitating or impeding young people’s transition into adult services. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):404. PubMed

- Brinkman WB, Sherman SN, Zmitrovich AR, et al. In their own words: adolescent views on ADHD and their evolving role managing medication. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(1):53–61. PubMed

- Andersson Frondelius I, Ranjbar V, Danielsson L. Adolescents’ experiences of being diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a phenomenological study conducted in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e031570. PubMed CrossRef

- Charach A, Fernandez R. Enhancing ADHD medication adherence: challenges and opportunities. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(7):371. PubMed CrossRef

- Baren M. ADHD in adolescents: will you know it when you see it? Contemp Pediatr. 2002;4:124.

- Sodano SM, Tamulonis JP, Fabiano GA, et al. Interpersonal problems of young adults with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Atten Disord. 2021;25(4):562–571. PubMed CrossRef

- Caci H, Asherson P, Donfrancesco R, et al. Daily life impairments associated with childhood/adolescent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as recalled by adults: results from the European Lifetime Impairment Survey. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(2):112–121. PubMed CrossRef

- Fridman M, Banaschewski T, Sikirica V, et al. Factors associated with caregiver burden among pharmacotherapy-treated children/adolescents with ADHD in the Caregiver Perspective on Pediatric ADHD Survey in Europe. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:373–386. PubMed

- Sikirica V, Flood E, Dietrich CN, et al. Unmet needs associated with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in eight European countries as reported by caregivers and adolescents: results from qualitative research. Patient. 2015;8(3):269–281. PubMed CrossRef

- Brinksma DM, Hoekstra PJ, de Bildt A, et al. Parental rejection in early adolescence predicts a persistent ADHD symptom trajectory across adolescence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32(1):139–153. PubMed CrossRef

- Faraone SV, Larsson H. Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(4):562–575. PubMed CrossRef

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Raggi VL, Clarke TL, et al. Associations between maternal attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and parenting. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36(8):1237–1250. PubMed CrossRef

- Whittle S, Simmons JG, Dennison M, et al. Positive parenting predicts the development of adolescent brain structure: a longitudinal study. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2014;8:7–17. PubMed

- Baweja R, Soutullo CA, Waxmonsky JG. Review of barriers and interventions to promote treatment engagement for pediatric attention deficit hyperactivity disorder care. World J Psychiatry. 2021;11(12):1206–1227. PubMed CrossRef

- Titheradge D, Godfrey J, Eke H, et al. Why young people stop taking their attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication: a thematic analysis of interviews with young people. Child Care Health Dev. 2022;48(5):724–735. PubMed CrossRef

- Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Spencer T, et al. Do stimulants protect against psychiatric disorders in youth with ADHD? A 10-year follow-up study. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):71–78. PubMed

- Farahbakhshian S, Ayyagari R, Barczak DS, et al. Disruption of pharmacotherapy during the transition from adolescence to early adulthood in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a claims database analysis across the USA. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(5):575–589. PubMed CrossRef

- Rao K, Carpenter DM, Campbell CI. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication adherence in the transition to adulthood: associated adverse outcomes for females and other disparities. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69(5):806–814. PubMed CrossRef

- Lundin C, Wikman A, Wikman P, et al. Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of depression among young women with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62(6):665–674. PubMed CrossRef

- McCarthy S. Pharmacological interventions for ADHD: how do adolescent and adult patient beliefs and attitudes impact treatment adherence? Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:1317–1327. PubMed CrossRef

- Kamimura-Nishimura KI, Brinkman WB, Froehlich TE. Strategies for improving ADHD medication adherence. Curr Psychiatr. 2019;18(8):25–38. PubMed

- Emilsson M, Gustafsson P, Öhnström G, et al. Impact of personality on adherence to and beliefs about ADHD medication, and perceptions of ADHD in adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):139. PubMed

- Pfeifer JH, Berkman ET. The development of self and identity in adolescence: neural evidence and implications for a value-based choice perspective on motivated behavior. Child Dev Perspect. 2018;12(3):158–164. PubMed CrossRef

- Meeus W, Iedema J, Maassen G, et al. Separation-individuation revisited: on the interplay of parent-adolescent relations, identity and emotional adjustment in adolescence. J Adolesc. 2005;28(1):89–106. PubMed

- Pfeifer JH, Masten CL, Borofsky LA, et al. Neural correlates of direct and reflected self-appraisals in adolescents and adults: when social perspective taking informs self-perception. Child Dev. 2009;80(4):1016–1038. PubMed CrossRef

- Krueger M, Kendall J. Descriptions of self: an exploratory study of adolescents with ADHD. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2001;14(2):61–72. PubMed CrossRef

- Cortese S, Asherson P, Sonuga-Barke E, et al. ADHD management during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidance from the European ADHD Guidelines Group. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):412–414. PubMed

- Breaux R, Dvorsky MR, Marsh NP, et al. Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: protective role of emotion regulation abilities. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;62(9):1132–1139. PubMed CrossRef

- Dvorsky MR, Breaux R, Cusick CN, et al. Coping with COVID-19: longitudinal impact of the pandemic on adjustment and links with coping for adolescents with and without ADHD. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2022;50(5):605–619. PubMed CrossRef

- Sibley MH, Ortiz M, Gaias LM, et al. Top problems of adolescents and young adults with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:190–197. PubMed CrossRef

- Becker SP, Breaux R, Cusick CN, et al. Remote learning during COVID-19: examining school practices, service continuation, and difficulties for adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(6):769–777. PubMed CrossRef

- Ra CK, Cho J, Stone MD, et al. Association of digital media use with subsequent symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adolescents. JAMA. 2018;320(3):255–263. PubMed

- Pluhar E, Kavanaugh JR, Levinson JA, et al. Problematic interactive media use in teens: comorbidities, assessment, and treatment. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:447–455. PubMed CrossRef

- Berloffa S, Salvati A, D’Acunto G, et al. Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Children (Basel). 2022;9(3):428. PubMed

- Shuai L, He S, Zheng H, et al. Influences of digital media use on children and adolescents with ADHD during COVID-19 pandemic. Glob Health. 2021;17(1):48.

- Le HH, Hodgkins P, Postma MJ, et al. Economic impact of childhood/adolescent ADHD in a European setting: The Netherlands as a reference case. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(7):587–598. PubMed CrossRef

- Schein J, Adler LA, Childress A, et al. Economic burden of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder among children and adolescents in the United States: a societal perspective. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):193–205. PubMed CrossRef

- Kooij JJS, Bijlenga D, Salerno L, et al. Updated European Consensus Statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;56:14–34. PubMed

- Coghill D, Banaschewski T, Cortese S, et al. The management of ADHD in children and adolescents: bringing evidence to the clinic: perspective from the European ADHD Guidelines Group (EAGG). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32(8):1337–1361. PubMed CrossRef

- Faraone SV, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, et al. The world federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;128:789–818. PubMed CrossRef

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE guideline Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management 2018. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87/resources/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-diagnosis-and-management-pdf1837699732933

- Kim M, King MD, Jennings J. ADHD remission, inclusive special education, and socioeconomic disparities. SSM Popul Health. 2019;8:100420. PubMed CrossRef

- Drechsler R, Brem S, Brandeis D, et al. ADHD: current concepts and treatments in children and adolescents. Neuropediatrics. 2020;51(5):315–335. PubMed CrossRef

- 125. Christensen L, Sasané R, Hodgkins P, et al. Pharmacological treatment patterns among patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: retrospective claims based analysis of a managed care population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(4):977–989. PubMed CrossRef

- López FA, Leroux JR. Long-acting stimulants for treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: a focus on extended-release formulations and the prodrug lisdexamfetamine dimesylate to address continuing clinical challenges. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2013;5(3):249–265. PubMed

- Chan E, Fogler JM, Hammerness PG. Treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in adolescents: a systematic review. JAMA. 2016;315(18):1997–2008. PubMed

- Faraone SV. Using meta-analysis to compare the efficacy of medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in youths. P T. 2009;34(12):678–694. PubMed

- Nagy P, Häge A, Coghill DR, et al. Functional outcomes from a head-to-head, randomized, double-blind trial of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate and atomoxetine in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and an inadequate response to methylphenidate. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(2):141–149. PubMed

- Spencer TJ, Brown A, Seidman LJ, et al. Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: a qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging-based neuroimaging studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):902–917. PubMed CrossRef

- Nakao T, Radua J, Rubia K, et al. Gray matter volume abnormalities in ADHD: voxel-based meta-analysis exploring the effects of age and stimulant medication. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(11):1154–1163. PubMed CrossRef

- Inguaggiato E, Sgandurra G, Cioni G. Brain plasticity and early development: implications for early intervention in neurodevelopmental disorders. Neuropsychiatr Enfance Adolesc. 2017;65(5):299–306.

- Uddin LQ, Dajani DR, Voorhies W, et al. Progress and roadblocks in the search for brain-based biomarkers of autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(8):e1218. PubMed CrossRef

This PDF is free for all visitors!

Save

Cite