Abstract

Objective: Some evidence has shown that problematic social media use (PSMU) is linked to anxiety. However, the nature of this relationship remains unclear, controversial, and poorly addressed due, among others, to a lack of examination of potential moderating and mediating variables. The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that trait mindfulness may act as a moderator in the association between PSMU and symptoms of anxiety in a sample of university students from Lebanon.

Methods: We carried out a cross-sectional study among 363 students (mean age 22.65 years, 61.7% females) using an online survey. All participants were administered the Lebanese Anxiety Scale, the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory, and the Social Media Disorder Scale. Students were recruited through convenience sampling from several universities in Lebanon between July and September 2021.

Results: The multivariate analysis results showed that higher PSMU (B=0.88) was significantly related to more anxiety, whereas greater trait mindfulness (B= −0.42) was significantly related to less anxiety. The interaction of PSMU by mindfulness was significantly associated with anxiety (B=0.04; t357 = 2.34; P= .020). At low levels of mindfulness, higher PSMU was significantly associated with high levels of anxiety; anxiety levels decrease with moderate and high levels of mindfulness, respectively, despite the same level of high PSMU.

Conclusion: Findings open up possibilities for new therapeutic approaches when dealing with PSMU among university students. Although further longitudinal studies are required, we preliminarily suggest that the use of trait mindfulness–based interventions may help reduce anxiety levels in students who present with severe PSMU.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2024;26(2):23m03664

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

The use of social media has rapidly grown worldwide. Active social media users increased by 21% between 2015 and 2017.1 A meta-analysis conducted in 2021 synthesizing the prevalence rates of social media addiction showed that there were wide variations in the prevalence estimates across studies and countries, ranging from 0% to 82%.2 Indeed, today’s youth have grown up in a world in which internet technologies are present everywhere and used on a daily basis and are thus referred to as “digital natives.”3 As such, young people may be more vulnerable to experiencing problematic social media use (PSMU), which has been shown to also be on the global rise.4 PSMU refers to inappropriate patterns of social media use5 that are linked to increased distress and decreased well-being.6 A substantial proportion of university students were reported to be at risk of PSMU in various countries all over the world, including the United States,7 China,8 Malaysia,9 Spain,10 Turkey,11 Tunisia,12 and Lebanon.13 With social media being a salient part of youth’s daily lives, problematic use is not without effects on their health. There is evidence supporting that PSMU is associated with a wide range of negative mental health outcomes,14 including development into unhealthy addictive behavior,15 poor memory,16 poor sleep quality,17 low well-being,18 depression, increased risk of suicidal ideation/behavior,19 and anxiety.20,21

LINK BETWEEN SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND ANXIETY

The present study particularly focused on the link between PSMU and anxiety in students for several reasons. First, cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings revealed that heavy social media use leads to anxiety among students,22,23 which itself can translate into multiple negative outcomes including heightened risk of psychopathology, suicidal feelings, impaired functioning, altered academic performance, and even dropping out of school.24 Second, given their age termed as emerging adulthood, students are at heightened vulnerability to heavy use of social media,25,26 to its detrimental effects,27 and more generally to subsequent mental health problems,28 including anxiety.29 According to the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors, anxiety represented the most frequent mental health problem among students, with prevalence rates having increased from 50.6% in 2016 to 60.7% in 2019.30,31 Third, previous cross-cultural research on this topic identified variations in prevalence rates and detrimental effects of addiction to online social networking among students from different countries and culture groups. Tang et al32 have, for example, found that addicted US students were at increased risk of anxiety compared to their Asian counterparts, suggesting that prevention and intervention approaches tailored to the specific cultural context of students are needed.32 Existing literature suggests that previous findings on PSMU and its association with negative mental health indicators cannot be applied to other student populations from different cultural backgrounds such as those from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Fourth, some mixed results have been reported on the association between social media use and anxiety. Some studies found positive but “weak,” “negligible” associations between these entities.22,33 Others, however, found no relationship between youth social media use and anxiety. Indeed, as previously stated, social media users may experience positive effects such as more social interactions and relationships and are thus less likely to report anxiety symptoms.34 In sum, the nature of the relationship between social media use and anxiety is still unclear, controversial, and poorly addressed due, among others, to a lack of moderating and mediating factors.33,35–37

TRAIT MINDFULNESS AS A MODERATOR OF THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND ANXIETY

To contribute to the clarification of this still contentious issue, mindfulness is proposed to be a relevant moderator for decreasing the negative outcomes of social media use on anxiety. A moderator designates a factor that may affect either the strength or the direction of the relationship between an independent (social media use in this study) variable and a dependent (here, anxiety) variable.38 Mindfulness refers to the ability to bring one’s complete attention to the experiences occurring in the present moment in a nonjudgmental or accepting way.39 Since mindfulness-based interventions have proven effective in improving psychological outcomes40 and well-being,41 studying the mindfulness concept as an inherent human trait, or a “mindful disposition,” has attracted increased research attention.42 Trait mindfulness has been shown to be negatively associated with anxiety symptoms and their related factors, including anxiety sensitivity and perceived stress.43,44 Indeed, mindful individuals have acceptance and nonjudgmental moment-to-moment awareness of their internal emotions, thoughts, behaviors, and surrounding external environments45–47 and are thus less prone to be distracted by negative emotions or anxiety.48,49

On the other hand, it has been suggested that having high levels of mindful awareness significantly decreases the occurrence and negative effects of problematic internet use due to less preference for online interactions and less reliance on social media for mood regulation.50 In addition, trait mindfulness can help social media users be less attentive to unpleasant experiences on social media (eg, negative feedback) and therefore less affected by such factors.51 Therefore, making the prediction that trait mindfulness may affect the relationship between social media use and anxiety is based on empirical precedent, as previous studies have provided indirect evidence supporting the possibility that trait mindfulness may weaken the negative impact of social media use on psychological distress. For example, prior studies52–55 have indicated that highly mindful individuals are capable of resisting the urge to use social media, which in turn results in increased work productivity and reduced psychological distress. Therefore, mindfulness seems to be a determinant factor that can balance the positive and negative outcomes that people obtain from social media. People who are mindful of their behavior know what they are doing. They are capable of regulating their social media use behavior in an effective way and not being subsumed by unpleasant or pleasant experiences via social media that may possibly cause them psychological distress.53

As such, trait mindfulness has been suggested to be a potential personal resource in buffering the relationship between mental health issues and PSMU.56 Hence, there is a strong need for investigation into the theoretically driven hypothesis that trait mindfulness can moderate the link between the severity of PSMU and anxiety levels in young adults.

THE PRESENT STUDY

As prior consistent evidence suggested a positive connection between PSMU symptoms and anxiety, further efforts need to be directed to examine modifiable moderating factors (eg, trait mindfulness) that may affect this relationship. Additional evidence providing support to trait mindfulness as a moderator can help design and implement mindfulness-based techniques that promote and cultivate mindfulness within low mindful individuals and subsequently decouple the association between PSMU symptoms and anxiety. To this end, this study sought to address shortcomings of the available literature and contribute findings from a, so far, under-researched country and region. We thus aimed to test the hypothesis that trait mindfulness may act as a moderator in the association between PSMU and symptoms of anxiety in a sample of university students from Lebanon.

METHODS

Sample and Procedure

A cross-sectional design was adopted in this study. University students aged over 18 years and willing to participate were recruited through convenience sampling through several universities in Lebanon between July and September 2021. A web-based link to the survey was used to collect data. It included the consent form, information form (purpose of the current study, voluntariness of consent to research, and anonymity), and a self-administered questionnaire in the Arabic language. The questionnaire required ∼20 minutes to complete. No compensation was offered. Students who refused to complete the survey were excluded.57–59 The Psychiatric Hospital of the Cross Ethics and Research Committee approved this study protocol (HPC-007-2021).

Minimal Sample Size Calculation

According to the G-power, a minimum of 316 students was deemed necessary to have enough statistical power, based on a risk of error of 5%, a power of 80%, f 2 = 2.5%, and 10 factors to be entered in the multivariate analysis.

Questionnaire and Variables

The questionnaire was composed of different sections. The first section asked questions on participants’ sociodemographic characteristics: gender, age, household crowding index (which was calculated by dividing the number of persons in the house by the number of rooms in the house excluding the bathrooms and kitchen60), and marital status. The physical activity index was calculated by multiplying the intensity by the frequency by the time of physical activity.61 Body mass index was calculated from self-reported weight and height. The second section of the questionnaire included the following scales.

Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory. The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) is a 14-item scale that measures trait mindfulness as a unidimensional construct (eg, accepting things nonjudgmentally and being aware of all the present-moment experiences). Items are scored based on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (rarely) to 4 (always). Greater total score reflects more trait mindfulness. This scale is validated in the Arabic language.62 The Cronbach alpha in this study was 0.92.

Social Media Disorder Scale. The Social Media Disorder Scale63 is a 9-item scale validated in the Arabic language.64 Higher scores indicate greater PSMU.63 The Cronbach alpha in this study was 0.79.

Lebanese Anxiety Scale. The Lebanese Anxiety Scale is a 10-item instrument assessing the severity of anxiety symptoms. The scale has been initially developed and validated in Arabic among both adults65 and adolescents.66 The first 7 questions are graded from 1 to 10, and the last 3 questions are graded from 1 to 4 based on the frequency of occurrence of symptoms. Higher scores indicate higher anxiety levels. The Cronbach alpha in this study was 0.89.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS software version 25 was used to conduct data analysis. The normality of the anxiety, PSMU, and trait mindfulness scores were verified via the skewness and kurtosis values varying between −2 and +2.67,68 A bivariate analysis using the Pearson correlation test served to assess the relationship between the anxiety score and other continuous variables, whereas the Student t test was used to compare 2 means (ie, gender and marital status). Model 1 in PROCESS MACRO for SPSS was used to test the significance of moderating effects; a simple slope test was used to analyze the relationship between PSMU and anxiety at different levels of mindfulness. The moderation analysis was adjusted over all sociodemographic variables that showed a P < .006 in the bivariate analysis after applying the Bonferroni correction (0.05/8; 8 represents the total number of variables in the analysis). The significance threshold was defined at P < .05.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and Other Characteristics of the Participants

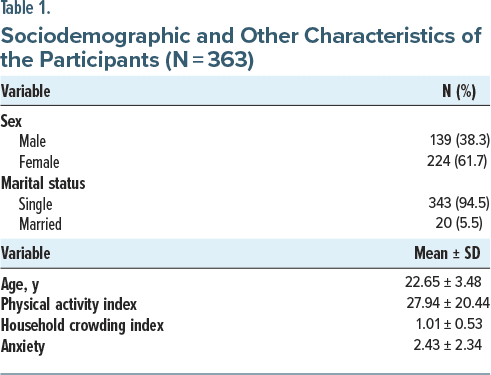

A total of 363 students participated in this study; their mean age was 22.65 ± 3.48 years, with 61.7% females. Other characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Bivariate Analysis of Factors Associated With Anxiety

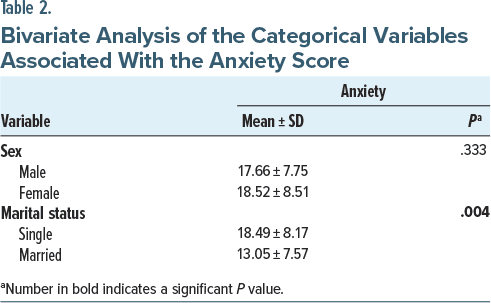

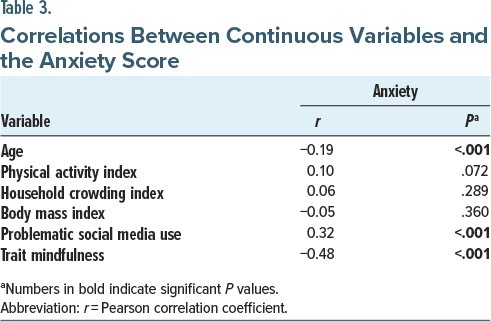

The bivariate analysis results are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. Single participants had a significantly higher mean anxiety score compared to married ones (18.49 vs 13.05; P = .004). Older age (r = −0.19) and higher trait mindfulness (r = −0.48) were significantly associated with less anxiety, whereas higher PSMU (r = 0.32) was significantly associated with more anxiety.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated With Anxiety

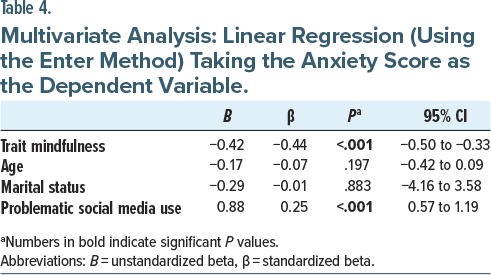

Higher PSMU (B=0.88) was significantly associated with more anxiety, whereas higher trait mindfulness (B =−0.42) was significantly associated with less anxiety (Table 4).

Moderation Analysis

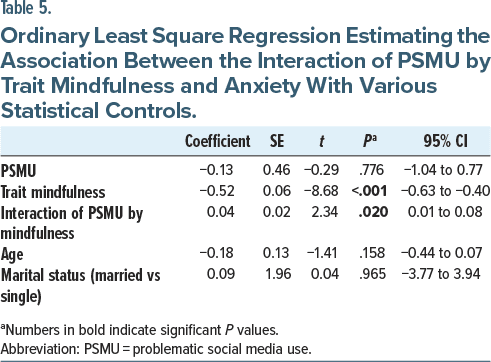

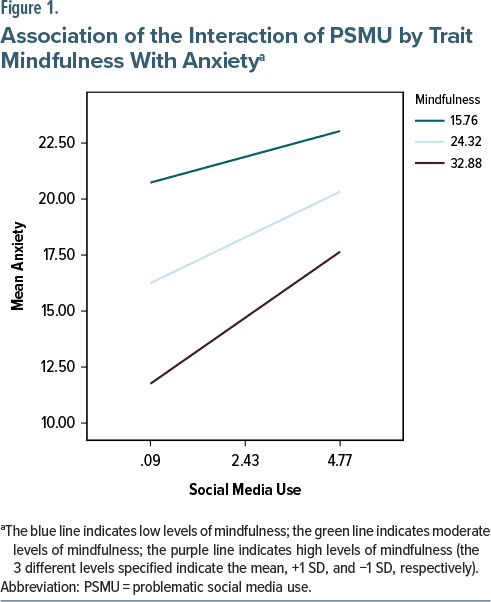

As seen in Table 5, the interaction of PSMU by mindfulness was significantly associated with anxiety (B=0.04; t357=2.34; P =.020). At low levels of mindfulness, higher PSMU was significantly associated with high levels of anxiety; anxiety levels decrease with moderate and high levels of mindfulness, respectively, despite the same level of high PSMU (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

Social media use is highly popular and widespread in Lebanon among young people in general69,70 and among university students in particular.71 As such, we believe that the present study could provide evidence for the extent of the problem among Lebanese students and identify potential actions towards overcoming it.

First, this study demonstrated that PSMU was positively and significantly associated with anxiety in the nonclinical university student sample. This result is in agreement with previous studies stipulating that individuals who engage in addictive social media use may experience more anxiety symptoms.72 Research has also reported that PSMU operates in a dose-response fashion in relation to anxiety among undergraduate students, with more time spent on social networks being related to worse anxiety.73 Our findings, along with literature data, do not allow for making any inferences about directionality and causality between the study variables. A bidirectional relationship has been previously suggested, with social media use being both attractive to already anxious users and a trigger of anxiety symptoms.74,75 Together, these observations identify a need for large longitudinal research studies to confirm our findings and establish the direction of causality.

In sum, despite the general agreement that PSMU is related to the development of subsequent anxiety, the possible mechanisms involved in this relationship remain poorly understood. Hence, it is important to further investigate the relation between PSMU and anxiety while considering potential moderators. Our hypothesis was supported, highlighting that trait mindfulness moderated the association between social media use disorder (SMUD) symptoms and anxiety levels. In accordance with these results, Liu et al46 found that mindful students tend to focus on their ongoing activities, which left them little opportunity to ruminate on negative social media content. Hong et al76 also found that mindfulness moderated the association between social media exposure and psychological distress in college students in China during COVID-19. Our findings are also broadly in line with a study that revealed that mindfulness moderated the association between social media use and burnout among Thai employees.53 These findings suggest that increasing students’ trait mindfulness may help buffer the negative effects of PSMU on anxiety symptoms.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The present study has a number of strengths that merit consideration. First, most of the previous research has focused on broad general concepts in relation to social media use, such as overall distress77,78 and well-being,79,80 while we aimed through this work to address the specific outcome of anxiety. Second, although it has been shown that older adolescents are more susceptible to experience emotional difficulties subsequent to social media use than early adolescents,22 most of the previous research has focused on young children, early adolescents, or adults81; however, limited empirical evidence exists regarding the effects of PSMU on students. Third, very few or no previous studies have been conducted in the MENA region to investigate the relationship between social media addiction and mental health concerns in a student population.

Our study has some limitations that need to be discussed. The main limitations lie in its cross-sectional design and its self-report nature. In addition, we used the FMI to assess students’ mindfulness traits. While this is a valid and widely used measure, it does not allow for an examination of the different facets of the multidimensional concept of mindfulness. Future research should address this point by using a multidimensional scale that captures various components of mindfulness, such as the Five Factor Mindfulness Questionnaire.82 Furthermore, other factors, such as frequency of use,5 time spent on social media,83 number of social media platforms used,84 and specific types of social media use (eg, entertainment, information seeking, and socially oriented uses),85 may account for some aspects of the relationship between SMUD and anxiety. Therefore, their role needs to be considered in future research.

Study Implications

Assisting students in tackling behavioral addictions and their negative consequences on mental health is important for the school counseling and educational staff. It is also recommended that university counselors educate students about negative outcomes relative to PSMU, intervene in a preventive manner with students who present with PSMU, and raise teachers’ and university staff’s awareness of PSMU and its detrimental effects on students’ mental health. We cannot change the reality that social media is an integral part of students’ everyday life. Thus, social media should be turned into a protective factor instead of serving as a stressor, by using it to offer online awareness applications about the link between PSMU and mental health difficulties including anxiety, as well as mental health interventions to the more vulnerable students.

Our findings provide potential insights on possible school-based mindfulness training that might help reduce anxiety levels in students who present with severe PSMU. Some mindfulness techniques previously described and tested in adolescent populations may be effective in helping students use social media in a positive manner,86 which could potentially alleviate its harmful effects. In light of prior evidence and present results, we also point to the need to design country-specific school-based intervention approaches that address problems related to PSMU among students in a given social and cultural context in order to maximize their efficiency.

CONCLUSION

The current findings provide additional support to the positive association between PSMU and anxiety and point to a moderating role of trait mindfulness in this association. Given the widespread use of social media among students, university-based awareness programs should inform students on how to revise their social media use habits to prevent possible symptoms of psychological distress. Also, findings open up possibilities for new therapeutic approaches when dealing with the modern scourge of PSMU among university students. We preliminarily suggest that the use of mindfulness training may help mitigate anxiety related to PSMU in this population. However, future longitudinal studies are required to establish causality and directionality in the relationship between PSMU and anxiety and to further investigate the underlying mechanisms linking these disorders.

Article Information

Published Online: April 16, 2024. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.23m03664

© 2024 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: October 28, 2023; accepted December 18, 2023.

To Cite: Fekih-Romdhane F, Obeid S, Rogoza R, et al. Moderating effect of trait mindfulness in the association between problematic social media use and anxiety among Lebanese university students. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2024;26(2):23m03664.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry “Ibn Omrane,” The Tunisian Center of Early Intervention in Psychosis, Razi Hospital, Manouba, Tunisia (Fekih-Romdhane); Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, Tunis El Manar University, Tunis, Tunisia (Fekih-Romdhane); Social and Education Sciences Department, School of Arts and Sciences, Lebanese American University, Jbeil, Lebanon (Obeid); Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw, Poland (Rogoza); University of Lleida, Lleida, Spain (Rogoza); School of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, Jounieh, Lebanon (Gerges, Hallit); Applied Science Research Center, Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan (Hallit).

Corresponding Authors: Souheil Hallit, PhD, School of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, PO Box 446, Jounieh, Lebanon ([email protected]); Sahar Obeid, PhD, Social and Education Sciences Department, School of Arts and Sciences, Lebanese American University, Jbeil, Lebanon ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank all participants in this project.

Additional Information: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as per the ethics committee policies but are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Clinical Points

- Higher problematic social media use (PSMU) was associated with more anxiety, whereas greater trait mindfulness was associated with less anxiety.

- The interaction of PSMU by mindfulness was significantly associated with anxiety. At low levels of mindfulness, higher PSMU was significantly associated with high levels of anxiety; anxiety levels decrease with moderate and high levels of mindfulness, respectively, despite the same level of high PSMU.

- We preliminarily suggest that the use of trait mindfulness–based interventions may help reduce anxiety levels in students who present with severe PSMU.

References (86)

- Kemp S. Digital in 2017: Global Overview. We Are Social; 2017. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://wearesocial.com/sg/blog/2017/01/digital-in-2017-global-overview/

- Cheng C, Lau YC, Chan L, et al. Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addict Behav. 2021;117:106845. PubMed CrossRef

- Prensky M. Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. On Horizon. 2001;9(5):1–6. CrossRef

- Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z. Social networking addiction: an overview of preliminary findings. In: Rosenberg KP, Curtiss Feder L, eds. Behavioral Addictions: Criteria, Evidence, and Treatment. Elsevier Academic Press; 2014:119–141. CrossRef

- Shensa A, Escobar-Viera CG, Sidani JE, et al. Problematic social media use and depressive symptoms among U.S. young adults: a nationally-representative study. Soc Sci Med. 2017;182:150–157. PubMed CrossRef

- Huang C. A meta-analysis of the problematic social media use and mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;68(1):12–33. PubMed CrossRef

- Turel O, Brevers D, Bechara A. Time distortion when users at-risk for social media addiction engage in non-social media tasks. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;97:84–88. PubMed CrossRef

- Jiang Q, Li Y, Shypenka V. Loneliness, individualism, and smartphone addiction among international students in China. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2018;21(11):711–718. PubMed CrossRef

- Jafarkarimi H, Sim ATH, Saadatdoost R, et al. Facebook addiction among Malaysian students. Int J Inf Educ Technol. 2016;6(6):465–418. CrossRef

- Aparicio-Martínez P, Ruiz-Rubio M, Perea-Moreno AJ, et al. Gender differences in the addiction to social networks in the Southern Spanish university students. Telemat Inform. 2020;46:101304.

- Altin M, Kivrak AO. The social media addiction among Turkish university students. J Educ Train Stud. 2018;6(12):13–20.

- Fekih-Romdhane F, Sassi H, Cheour M. The relationship between social media addiction and psychotic-like experiences in a large nonclinical student sample. Psychosis. 2021;13(4):349–360. CrossRef

- Awad E, El Khoury-Malhame M, Yakin E, et al. Association between desire thinking and problematic social media use among a sample of Lebanese adults: the indirect effect of suppression and impulsivity. PLoS One. 2022;17(11):e0277884. PubMed CrossRef

- Schønning V, Hjetland GJ, Aarø LE, et al. Social media use and mental health and well-being among adolescents – a scoping review. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1949. PubMed

- Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Online social networking and addiction—a review of the psychological literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(9):3528–3552. PubMed CrossRef

- Dagher M, Farchakh Y, Barbar S, et al. Association between problematic social media use and memory performance in a sample of Lebanese adults: the mediating effect of anxiety, depression, stress and insomnia. Head Face Med. 2021;17(1):6. PubMed CrossRef

- Woods HC, Scott H. #Sleepyteens: social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J Adolesc. 2016;51:41–49. PubMed CrossRef

- Kross E, Verduyn P, Demiralp E, et al. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e69841. PubMed CrossRef

- Brailovskaia J, Teismann T, Margraf J. Positive mental health mediates the relationship between Facebook addiction disorder and suicide-related outcomes: a longitudinal approach. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2020;23(5):346–350. PubMed CrossRef

- Barbar S, Haddad C, Sacre H, et al. Factors associated with problematic social media use among a sample of Lebanese adults: the mediating role of emotional intelligence. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(3):1313–1322. PubMed CrossRef

- Malaeb D, Salameh P, Barbar S, et al. Problematic social media use and mental health (depression, anxiety, and insomnia) among Lebanese adults: any mediating effect of stress? Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(2):539–549. PubMed CrossRef

- Thorisdottir IE, Sigurvinsdottir R, Kristjansson AL, et al. Longitudinal association between social media use and psychological distress among adolescents. Prev Med. 2020;141:106270. PubMed CrossRef

- Demirci K, Akgönül M, Akpinar A. Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. J Behav Addict. 2015;4(2):85–92. PubMed CrossRef

- American College Health Association. National College Health Assessment II: Fall 2017 Reference Group Data Report, Hanover. American College Health Association: 2018.

- Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, et al. Social Media & Mobile Internet Use Among Teens and Young Adults. Pew Internet and American Life Project. PewResearchCenter: 2010.

- Anderson M, Jiang J. Teens, Social Media and Technology 2018. Pew Research Center; 2018. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

- Przybylski AK, Murayama K, DeHaan CR, et al. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29(4):1841–1848. CrossRef

- Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(1):281–295. PubMed CrossRef

- McLaughlin KA, King K. Developmental trajectories of anxiety and depression in early adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43(2):311–323. PubMed CrossRef

- LeViness P, Gorman K, Braun L, et al. The Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors Annual Survey 2019. Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors; 2019. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.aucccd.org/assets/documents/Survey/2018%20aucccd%20survey-public-revised.pdf

- Reetz DR, Krylowicz B, Mistler B. The Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors Annual Survey. Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors; 2016. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.aucccd.org/director-surveys-public

- Tang CSK, Wu AMS, Yan ECW, et al. Relative risks of Internet-related addictions and mood disturbances among college students: a 7-country/region comparison. Public Health. 2018;165:16–25. PubMed CrossRef

- Keles B, McCrae N, Grealish A. A systematic review: the influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2020;25(1):79–93. CrossRef

- Grieve R, Indian M, Witteveen K, et al. Face-to-face or Facebook: can social connectedness be derived online? Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29(3):604–609. CrossRef

- McCrae N, Gettings S, Purssell E. Social media and depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review. Adolesc Res Rev. 2017;2:315–330. CrossRef

- Seabrook EM, Kern ML, Rickard NS. Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review. JMIR Ment Health. 2016;3(4):e50. PubMed CrossRef

- Huang C. Time spent on social network sites and psychological well-being: a meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2017;20(6):346–354. PubMed CrossRef

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. PubMed CrossRef

- Leroy H, Anseel F, Dimitrova NG, et al. Mindfulness, authentic functioning, and work engagement: a growth modeling approach. J Vocat Behav. 2013;82(3):238–247. CrossRef

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, et al. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(2):169–183. PubMed CrossRef

- Fekih-Romdhane F, Malaeb D, Hallit S, et al. Does mindfulness moderate the association between impulsivity and well-being in Lebanese university students? Int J Environ Health Res. 2024;34(3):1397–1409. PubMed CrossRef

- Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychol Inq. 2007;18(4):211–237. CrossRef

- Tomlinson ER, Yousaf O, Vittersø AD, et al. Dispositional mindfulness and psychological health: a systematic review. Mindfulness (N Y). 2018;9(1):23–43. PubMed CrossRef

- Bitar Z, Rogoza R, Hallit S, et al. Mindfulness among lebanese university students and its indirect effect between mental health and wellbeing. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):114. PubMed CrossRef

- Keng SL, Smoski MJ, Robins CJ. Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(6):1041–1056. PubMed CrossRef

- Liu QQ, Zhou ZK, Yang XJ, et al. Mobile phone addiction and sleep quality among Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;72:108–114. CrossRef

- Rodríguez-Ledo C, Orejudo S, Cardoso MJ, et al. Emotional intelligence and mindfulness: relation and enhancement in the classroom with adolescents. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2162. PubMed

- Farb NAS, Anderson AK, Mayberg H, et al. Minding one’s emotions: mindfulness training alters the neural expression of sadness. Emotion. 2010;10(1):25–33. PubMed CrossRef

- Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion. 2010;10(1):83–91. PubMed CrossRef

- Gámez-Guadix M, Calvete E. Assessing the relationship between mindful awareness and problematic Internet use among adolescents. Mindfulness. 2016;7(6):1281–1288.

- Valkenburg PM, Peter J, Schouten AP. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. CyberPsychol Behav. 2006;9(5):584–590. PubMed CrossRef

- Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, et al. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501–517. PubMed CrossRef

- Baker ZG, Krieger H, LeRoy AS. Fear of missing out: relationships with depression, mindfulness, and physical symptoms. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 2016;2(3):275–282. CrossRef

- Charoensukmongkol P. Mindful Facebooking: the moderating role of mindfulness on the relationship between social media use intensity at work and burnout. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(9):1966–1980. PubMed CrossRef

- Sriwilai K, Charoensukmongkol P. Face it, don’t Facebook it: impacts of social media addiction on mindfulness, coping strategies and the consequence on emotional exhaustion. Stress Health. 2016;32(4):427–434. PubMed CrossRef

- Majeed M, Irshad M, Fatima T, et al. Relationship between problematic social media usage and employee depression: a moderated mediation model of mindfulness and fear of COVID-19. Front Psychol. 2020;11:557987. PubMed CrossRef

- Awad E, Hallit S, Obeid S. Does self-esteem mediate the association between perfectionism and mindfulness among Lebanese university students? BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):256. PubMed CrossRef

- Fekih-Romdhane F, Sawma T, Obeid S, et al. Self-critical perfectionism mediates the relationship between self-esteem and satisfaction with life in Lebanese university students. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):4. PubMed CrossRef

- Fekih-Romdhane F, Haddad P, Roukoz R, et al. Does loneliness mediate the association between social media use disorder and sexual function in Lebanese university students? Int J Environ Health Res. 2024;34(3):1835–1846. PubMed CrossRef

- Melki IS, Beydoun HA, Khogali M, et al. National Collaborative Perinatal Neonatal (NCPNN). Household crowding index: a correlate of socioeconomic status and inter-pregnancy spacing in an urban setting. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(6):476–480. PubMed CrossRef

- Weary-Smith KA. Validation of the Physical Activity Index (PAI) as a Measure of Total Activity Load and Total Kilocalorie Expenditure During Submaximal Treadmill Walking. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Pittsburgh; 2007.

- Bitar Z, Fekih Romdhane F, Rogoza R, et al. Psychometric properties of the short form of the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory in the Arabic language. Int J Environ Health Res. 2023;11:1–12. CrossRef

- van den Eijnden RJJM, Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM. The Social Medial Disorder Scale. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;61:478–487. CrossRef

- Awad E, Rogoza R, Gerges S, et al. Association of social media use disorder and orthorexia nervosa among Lebanese university students: the indirect effect of loneliness and factor structure of the social media use disorder short form and the Jong-Gierveld loneliness scales. Psychol Rep. 2022 Oct;15:332941221132985. CrossRef

- Hallit S, Obeid S, Haddad C, et al. Construction of the Lebanese Anxiety Scale (LAS-10): a new scale to assess anxiety in adult patients. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2020;24(3):270–277. PubMed CrossRef

- Merhy G, Azzi V, Salameh P, et al. Anxiety among Lebanese adolescents: scale validation and correlates. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):288. PubMed CrossRef

- George D, Mallery P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Study Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update. Pearson Education India; 2011.

- Leguina A. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Taylor & Francis; 2015.

- Youssef L, Hallit R, Kheir N, et al. Social media use disorder and loneliness: any association between the two? Results of a cross-sectional study among Lebanese adults. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):56. PubMed CrossRef

- Youssef L, Hallit R, Akel M, et al. Social media use disorder and alexithymia: any association between the two? Results of a cross-sectional study among Lebanese adults. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(1):20–26. PubMed CrossRef

- Sabbah H, Berbari R, Khamis R, et al. The social media and technology addiction and its associated factors among university students in Lebanon using the media and technology usage and attitudes scale (MTUAS). J Comput Commun. 2019;7(11):88–106. CrossRef

- Schou Andreassen C, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, et al. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(2):252–262. PubMed CrossRef

- Hanna E, Ward LM, Seabrook RC, et al. Contributions of social comparison and self-objectification in mediating associations between Facebook use and emergent adults’ psychological well-being. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2017;20(3):172–179. PubMed CrossRef

- Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Social networking sites and addiction: ten lessons learned. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(3):311. PubMed CrossRef

- Shakya HB, Christakis NA. Association of Facebook use with compromised well-being: a longitudinal study. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(3):203–211. PubMed CrossRef

- Hong W, Liu RD, Ding Y, et al. Social media exposure and college students’ mental health during the outbreak of COVID-19: the mediating role of rumination and the moderating role of mindfulness. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2021;24(4):282–287. PubMed CrossRef

- Jensen M, George M, Russell M, Odgers C, et al. Young adolescents’ digital technology use and mental health symptoms: little evidence of longitudinal or daily linkages. Clin Psychol Sci. 2019;7(6):1416–1433. PubMed CrossRef

- Riehm KE, Feder KA, Tormohlen KN, et al. Associations between time spent using social media and internalizing and externalizing problems among US youth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(12):1266–1273. PubMed CrossRef

- Booker CL, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Gender differences in the associations between age trends of social media interaction and well-being among 10–15 year olds in the UK. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):321. PubMed CrossRef

- Orben A, Dienlin T, Przybylski AK. Social media’s enduring effect on adolescent life satisfaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(21):10226–10228. PubMed CrossRef

- Odgers CL, Jensen MR. Annual research review: adolescent mental health in the digital age: facts, fears, and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61(3):336–348. PubMed CrossRef

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, et al. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. PubMed CrossRef

- Vannucci A, Flannery KM, Ohannessian CM. Social media use and anxiety in emerging adults. J Affect Disord. 2017;207:163–166. PubMed CrossRef

- Primack BA, Shensa A, Escobar-Viera CG, et al. Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: a nationally-representative study among U.S. young adults. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;69:1–9. CrossRef

- Zhao L. The impact of social media use types and social media addiction on subjective well-being of college students: a comparative analysis of addicted and non-addicted students. Comput Hum Behav Rep. 2021;4:100122. CrossRef

- Weaver JL, Swank JM. Mindful connections: a mindfulness-based intervention for adolescent social media users. J Child Adolesc Couns. 2019;5(2):103–112. CrossRef

Please sign in or purchase this PDF for $40.

Save

Cite