Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2022;24(1):21com03149

To cite: Padala AP, Wilson KB, Das A. The opioid epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic: similarities in biology and differences in response to 2 public health crises. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2022;24(1):21com03149.

To share: https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.21com03149

© Copyright 2022 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

aCentral Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, Little Rock, Arkansas

bGeriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, Little Rock, Arkansas

cDepartment of Psychiatry, AdventHealth Orlando, Orlando, Florida

*Corresponding author: Aparna Das, MD, Department of Psychiatry, AdventHealth Orlando, 601 East Rollins St, Orlando, FL 32803 ([email protected]).

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a major public health problem impacting more than 26 million individuals.1 OUD has claimed over 500,000 American lives.2 In the US, there have been 3 waves of the opioid epidemic since the 1990s: first with prescription opioids, second with heroin, and third with fentanyl. The opioid epidemic reached its peak in 2017, with more than 47,000 opioid overdose deaths in the US that year alone.2 The economic cost of OUD from 2015 to 2018 was over $631 billion.3 During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there was a spike in OUD, possibly due to isolation, lack of access to in-person counseling, poor treatment of chronic pain, and increased stress. Opioid overdose deaths increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, reaching levels similar to the 2017 peak in some states.4

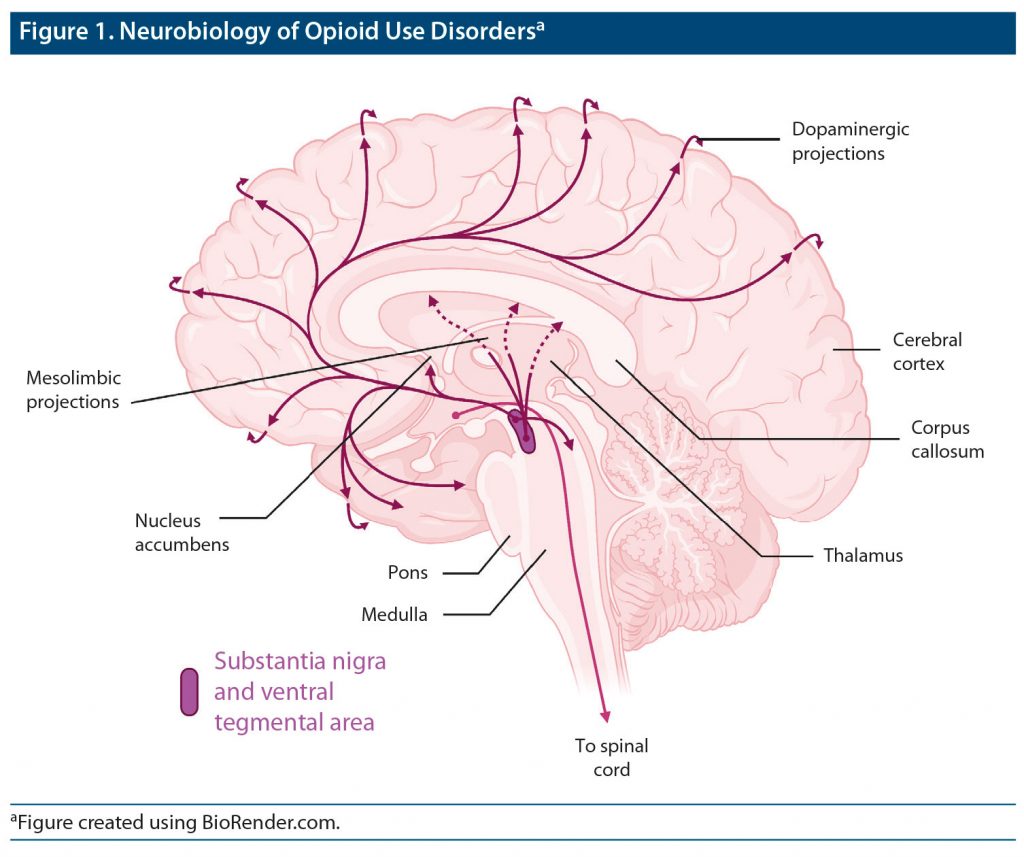

OUD is a chronic relapsing illness characterized by intense cravings and compulsive use despite negative consequences. The pleasurable effects experienced motivate repeated use.5 Opioid self-administration activates μ receptors, which results in dopamine (DA)–mediated euphoria.5 The mesolimbic DA projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to nucleus accumbens (NAc) are involved in OUD (Figure 1).6 Chronic use leads to neuroadaptation through decreased VTA mesolimbic and NAc DA neurotransmission, resulting in tolerance, wherein more substance must be used to experience the same level of euphoria.7

Many societal and systemic failures have led to the opioid crisis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. OUD is iatrogenic in many cases, with 21%–29% of patients misusing opioids that were prescribed for chronic pain and 8%–12% developing OUD.8 Instead of focusing on the neurobiology of OUD, patients are often blamed for the problem. Stigma, a fundamental cause of population health inequities, is multifaceted, ranging from self-stigma to structural stigma restricting prescription of medications for OUD.9 Medications for OUD are efficacious and evidence-based treatments that are known to significantly reduce opioid overdoses. Yet, only 11% of Black patients receive medications for OUD in some states.10 Black patients are less likely to receive medications for OUD in both short-term (odds ratio [OR] = 0.728; 95% CI, 0.677–0.783; P < .005) and long-term (OR = 0.725; 95% CI, 0.658–0.799; P < .005) treatment facilities compared to White patients.11 Fewer than 1 in 6 patients referred by the criminal justice system in the US had access to medications for OUD between 2007 and 2018.10 Racial disparities in OUD outcomes are increasing, as evidenced by the dramatic increase in the rate of death due to synthetic opioids for Black individuals in recent years—as much as 818% between 2014 and 2017—and the increase was highest for Blacks compared to all other race/ethnicities.12 In 2017, synthetic opioids accounted for nearly 70% of the opioid-related overdose deaths in Blacks compared to 59% in non-Hispanic Whites and 36% in Hispanics.12 A fresh perspective is needed to recognize the urgency of this medical crisis and efforts to treat the same.

Similarities and Differences Between OUD and the COVID-19 Pandemic

In many ways, the problems with the opioid epidemic are analogous to the COVID-19 pandemic. First, both are medical conditions, with OUD having a neurobiological basis. Second, both are more likely to spread among tightly knit clusters of people. Third, psychosocial factors such as socioeconomic status, location of residence, and access to health care play a role in their prevalence. Fourth, poor health legislation has had a huge impact on the spread of the virus because there were no uniform procedures in place to stop the spread, and, along the same vein, broad legislation to decriminalize substance use disorders remains lacking. Fifth, minorities are disproportionately affected by the pandemic and are less likely to receive treatment, as is also the case for those who would benefit from medication for OUD.11 Finally, both COVID-19 and OUD are worsened by stigma surrounding their treatments.13

The response to the COVID-19 pandemic has also faced multiple political, geographic, racial, and socioeconomic hurdles. Wearing a mask or getting vaccinated has become a hot button political issue in many states. Consequently, vaccination rates have varied dramatically across the states, with the highest numbers in the New England states compared to the lowest numbers in southern states like Mississippi and Arkansas. It is even more alarming to note that racial disparities also exist in vaccine uptake, with a high prevalence of vaccine hesitancy in Blacks, Hispanics, individuals with lower education, and those residing in rural areas.14 Thus, political and demographic factors continue to influence policies, access to care, and acceptance of available interventions for both COVID-19 and OUD.

Despite the similarities, our response to the 2 conditions was completely opposite. We criminalized those with OUD and stigmatized the problem instead of treating it. People with OUD often end up in prison, while people with COVID-19 receive treatment in a hospital setting. Although robust research has been conducted for both conditions, there was no US Food and Drug Administration emergency authorization for OUD treatment, no celebrities endorsing available treatments, and no incentives offered by the government or private companies’ Vax-a-Million lottery system. This disparity is by no means isolated and is a common trend that surrounds mental health issues.

Suggested Ways Forward

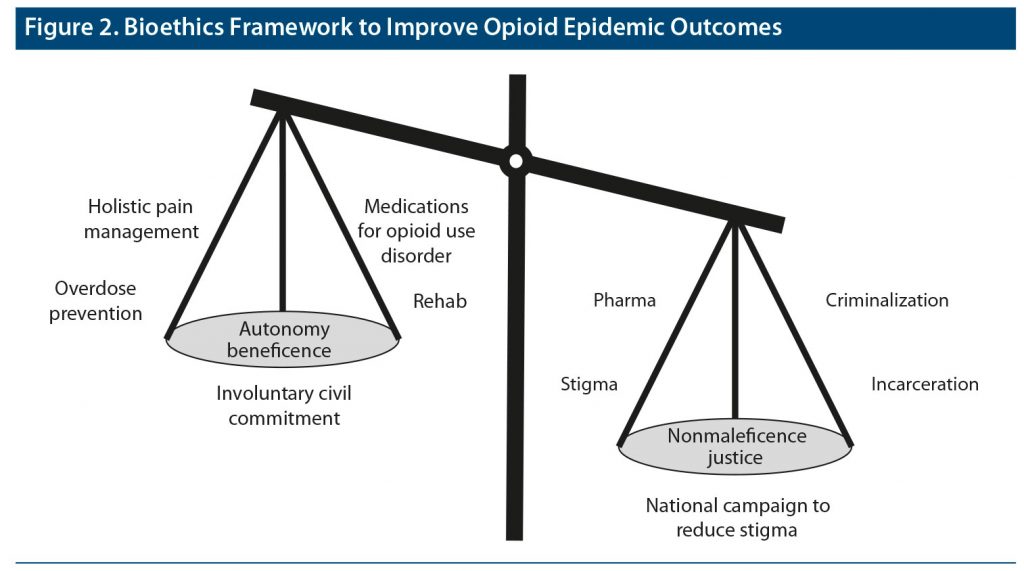

We need to treat OUD like a medical condition and bear in mind the tenets of bioethics as a framework (Figure 2). One important aspect of this framework to consider is autonomy. Some ways to respect autonomy include providing fresh disposable needles and antidotes like naloxone in homeless shelters and bars. One controversial form of treatment that needs to be considered when discussing autonomy is involuntary civil commitment (ICC). Although ICC prevents imminent overdose, it also takes away fundamental rights. Hence, ICC should be used as a last resort in a consensual process.15 Justice is another important ethical principle to consider due to the existing inequities in treatments for OUD. OUD treatments should be made available to all regardless of their background. The same legal framework for drug-related offenses should be extended to all. Beneficence should guide health care providers to treat pain with holistic approaches. Nonmaleficence should guide us to hold health care providers accountable for overprescribing or underprescribing pain medications and medications for OUD, respectively, while reducing barriers to prescribing medications for OUD. A national campaign with celebrities could help reduce stigma about OUD. Since stigma is a key driver of OUD behavior, careful selection of language can make a huge impact. Some suggested language includes the use of “person with OUD” instead of “addict,” use of “opioid free” instead of “clean,” and use of “positive test result” instead of “dirty test result.” With societal buy-in, we can save many lives, and there are some positive signs out there already. There is evidence that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has increased medication for OUD use among minorities, reducing the disparity in OUD treatment.10 Since lack of health insurance, poor socioeconomic status, and unemployment are known to be associated with poor access to OUD treatment, the ACA expanded health coverage and mandated health insurance plans to cover OUD treatments. In the states that implemented the ACA-funded Medicaid expansion, there was increased use of medications for OUD among Black patients and a reduction in treatment disparity.10 We believe that with some effort, positive changes can be made that can lead to better handling of the opioid epidemic.

Received: September 21, 2021.

Published online: January 20, 2022.

Potential conflicts of interest: None.

Funding/support: None.

References (15)

- Shulman M, Wai JM, Nunes EV. Buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder: an overview. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(6):567–580. PubMed CrossRef

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality. CDC WONDER, Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC website. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://wonder.cdc.gov

- Tam CC, Zeng C, Li X. Prescription opioid misuse and its correlates among veterans and military in the United States: a systematic literature review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;216:108311. PubMed CrossRef

- Vieson J, Yeh AB, Lan Q, et al. During the COVID-19 pandemic, opioid overdose deaths revert to previous record levels in Ohio [published online ahead of print June 24, 2021]. J Addict Med. 2021. PubMed CrossRef

- Koob GF, Stinus L, Le Moal M, et al. Opponent process theory of motivation: neurobiological evidence from studies of opiate dependence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1989;13(2-3):135–140. PubMed CrossRef

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(8):760–773. PubMed CrossRef

- Nestler EJ. Cellular and Molecular Mechanism of Drug Addiction. In: Charney DS, Nestler EJ, eds. Neurobiology of Mental Illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004:698–709.

- Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156(4):569–576. PubMed CrossRef

- McCradden MD, Vasileva D, Orchanian-Cheff A, et al. Ambiguous identities of drugs and people: a scoping review of opioid-related stigma. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;74:205–215. PubMed CrossRef

- Johnson NL, Choi S, Herrera CN. Black clients in expansion states who used opioids were more likely to access medication for opioid use disorder after ACA implementation [published online ahead of print June 11, 2021]. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;108533. PubMed CrossRef

- Stahler GJ, Mennis J, Baron DA. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and their effects on residential drug treatment outcomes in the US. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;226:108849. PubMed CrossRef

Kiechle JE, Gonzalez CM. The Opioid Crisis and the Black/African American Population: an Urgent Issue (SAMHSA). 2020. Publication No. PEP20-05-02-001. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/The-Opioid-Crisis-and-the-Black-African-American-Population-An-Urgent-Issue/PEP20-05-02-001

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. Accessed June 25, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html

- Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, et al. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):270–277. PubMed CrossRef

- Evans EA, Harrington C, Roose R, et al. Perceived benefits and harms of involuntary civil commitment for opioid use disorder. J Law Med Ethics. 2020;48(4):718–734. PubMed CrossRef

Please sign in or purchase this PDF for $40.

Save

Cite