Because this piece does not have an abstract, we have provided for your benefit the first 3 sentences of the full text.

To the Editor: Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) is a manifestation arising from compression or obstruction of the superior vena cava (SVC), characterized by edema of the face, neck, trunk, and upper extremities as well as collateral venous distension of the neck and anterior chest wall. Mostly caused by mediastinal malignancies, SVCS can be secondary to SVC thrombosis in 1%-5% of cases. Amphetamine-type stimulants have been extensively associated with psychiatric conditions, namely mood and psychotic episodes.

Psychotic Symptoms Associated With Superior Vena Cava Syndrome Following Methamphetamine Abuse

To the Editor: Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) is a manifestation arising from compression or obstruction of the superior vena cava (SVC), characterized by edema of the face, neck, trunk, and upper extremities as well as collateral venous distension of the neck and anterior chest wall.1 Mostly caused by mediastinal malignancies, SVCS can be secondary to SVC thrombosis in 1%-5% of cases.2 Amphetamine-type stimulants have been extensively associated with psychiatric conditions, namely mood and psychotic episodes. They can also cause systemic effects3 including vascular conditions.4

The present case highlights for the first time an association between psychosis and SVCS in a patient with a history of methamphetamine abuse.

Case report. Mr A, a 24-year-old man, presented with acute agitation and aggressive behavior. At admission, self-neglect, delusional speech, auditory and cenesthetic hallucinations, inappropriate uncontrolled laughter, perseveration, and misrecognition were reported. No medical history or previous admission was reported, and no medical record was available. He was homeless, and all of his relatives lived in Morocco.

After an initial 3-day sedation, he was hospitalized in the psychiatry department for 6 months.

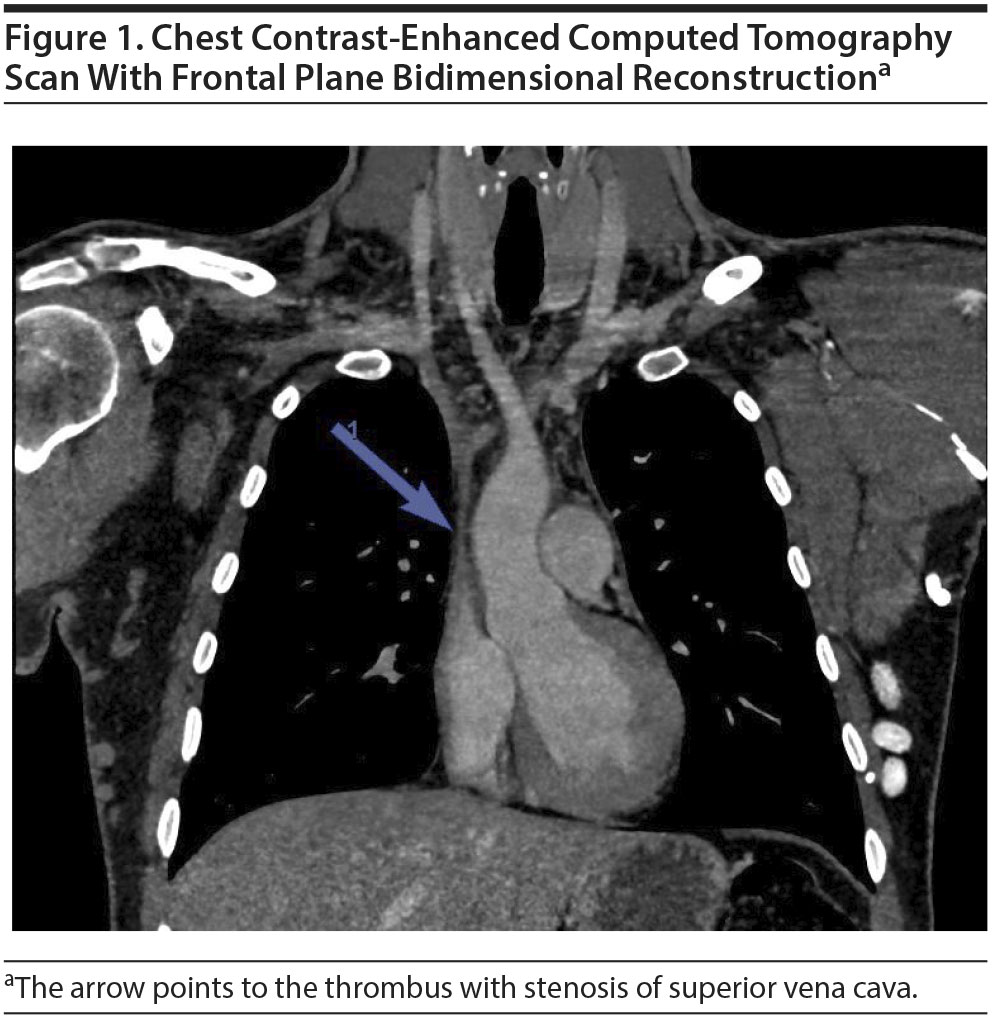

Physical examination at admission revealed a face and neck edema and voluminous collateral blood-flow network of the anterior chest wall veins, consistent with SVCS. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1) revealed SVC thrombosis with distended collateral vasculature and stenosis of SVC. Intramuscular heparin (tinzaparin 14,000 UI/d) was administered to prevent further complications. Coagulation test results were normal, and thrombophilia screening was negative. No evidence was found for cryoglobulinemia, antiphospholipid syndrome, or antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis. Myeloproliferative neoplasm, celiac, Biermer, and Behçet diseases were ruled out.

As thoracic CT scan and full body positron emission tomography scan found no evidence of neoplasia, a paraneoplastic etiology was rejected. Brain CT and electroencephalography findings were normal. Brain single-photon emission computerized tomography showed mild frontal cortex and anterior cingulum hypoperfusion.

After a 6-month period of continued psychotic symptoms, Mr A was diagnosed with schizophrenia according to the Mini DSM-5.5 His Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)6 total score was 133 (severe current psychotic symptomatology; Positive scale = 35, Negative scale = 35, General Psychopathology scale = 63).

The patient was first administered risperidone 6 mg/d without success. Olanzapine 20 mg/d was stopped because of weight gain, and aripiprazole 15 mg/d was discontinued after akathisia onset. Mr A’s symptoms were alleviated with clozapine 350 mg/d.

Due to the improvement in psychotic symptoms, the patient’s medical history was then reported and included acute rheumatic fever at 11 years of age, first drug abuse at 18 (with occasional cannabis and cocaine abuse), and, at the age of 24, high doses of crystal methamphetamine ("ice") sniffed over 10 days.

Mr A could remember clearly the sudden swelling of his upper limbs, face, neck, and trunk that had occurred the day after his last use of crystal methamphetamine and persisted ever since. Collecting data about his medical condition during the year before his admission has not been possible, and the date of onset of psychosis could not be specified due to memory loss and the absence of relatives. Pathological traveling across Libya, Serbia, and Germany during the weeks before admission suggests that the psychosis had been occurring for several weeks at the time of admission.

Despite several radiologic interventions, the thrombus was unremovable. Tinzaparin was replaced by an oral anticoagulant, rivaroxaban.

Mr A’s PANSS total score after 6 months of treatment with clozapine (blood clozapine level of 628 ng/mL) was 85 (Positive scale = 10, Negative scale = 25, General Psychopathology scale = 50). The residual psychotic symptoms were mostly cognitive, including difficulty in abstract thinking, stereotyped thinking, anxiety, unusual thought content, avolition, and poor impulse control.

Amphetamines are well known to induce both psychotic symptoms7 and venous thrombosis (cerebral8 or renal9). However, the present case report is the first to relate amphetamine-induced schizophrenia with deep venous thrombosis, prior to psychotropic medication use and without coagulation disorders.

In this case, methamphetamine had been taken in its crystal form, believed to be particularly harmful because of its high potency compared to other forms.10

The self-reported sudden swelling highlights the chronological relationship between crystal methamphetamine and thrombosis. This is consistent with data suggesting that thrombotic SVCS is more brutal than compressive SVCS.11

Amphetamines have a direct vascular toxicity that may be due to the induction of inflammatory genes in small vessel endothelial cells.12

It has been hypothesized that psychosis may result from microvascular brain damage.13 This risk may be particularly increased in case of genetic predisposition. Inflamed microvessels lose their coupling with astrocytes, leading to dysregulated cerebral blood flow and damaged blood-brain barrier.13 The direct action of methamphetamine on vascular endothelium may induce acute opening of the blood-brain barrier, while striatal effects and resultant neuroinflammatory signaling could lead to its chronic dysfunction.14

Schizophrenia has been extensively associated with abnormal immuno-inflammatory processes.

Future studies should determine the prevalence of SVCS in subjects with schizophrenia who have a history of methamphetamine use disorder in order to develop prevention and treatment strategies.

References

1. Straka C, Ying J, Kong F-M, et al. Review of evolving etiologies, implications and treatment strategies for the superior vena cava syndrome. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):229. PubMed CrossRef

2. Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006;85(1):37-42. PubMed CrossRef

3. Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM. Methamphetamine abuse: a perfect storm of complications. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(1):77-84. PubMed CrossRef

4. Hermens DF, Lubman DI, Ward PB, et al. Amphetamine psychosis: a model for studying the onset and course of psychosis. Med J Aust. 2009;190(4 suppl):S22-S25. PubMed

5. American Psychiatric Association. Mini DSM-5 Critרres Diagnostiques. Crocq MA, Guelfi JD, trans-eds. Issy-les-Moulineaux, France: Elsevier Masson SAS; 2016.

6. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-276. PubMed CrossRef

7. Bramness JG, Gundersen טH, Guterstam J, et al. Amphetamine-induced psychosis: a separate diagnostic entity or primary psychosis triggered in the vulnerable? BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):221. PubMed CrossRef

8. Rothwell PM, Grant R. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis induced by "ecstasy." J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56(9):1035. PubMed CrossRef

9. Eldehni MT, Roberts ISD, Naik R, et al. Case report of ecstasy-induced renal venous thrombosis. NDT Plus. 2010;3(5):459-460. PubMed CrossRef

10. Lappin JM, Roxburgh A, Kaye S, et al. Increased prevalence of self-reported psychotic illness predicted by crystal methamphetamine use: evidence from a high-risk population. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;38:16-20. PubMed CrossRef

11. Cohen R, Mena D, Carbajal-Mendoza R, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome: a medical emergency? Int J Angiol. 2008;17(1):43-46. PubMed CrossRef

12. Lee YW, Hennig B, Yao J, et al. Methamphetamine induces AP-1 and NF-kappaB binding and transactivation in human brain endothelial cells. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66(4):583-591. PubMed CrossRef

13. Hanson DR, Gottesman II. Theories of schizophrenia: a genetic-inflammatory-vascular synthesis. BMC Med Genet. 2005;6(1):7. PubMed CrossRef

14. Turowski P, Kenny B-A. The blood-brain barrier and methamphetamine: open sesame? Front Neurosci. 2015;9:156. PubMed CrossRef

aDepartment of Psychiatry, La Conception Hospital, Assistance Publique-H×´pitaux de Marseille 13005, Marseille, France

Potential conflicts of interest: None.

Funding/support: None.

Patient consent: Patient consent was obtained to publish the case. Information has been de-identified to protect anonymity.

Published online: November 1, 2018.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2018;20(6):17l02253

To cite: Dircks S, Dubois M, Dassa D. Psychotic symptoms associated with superior vena cava syndrome following methamphetamine abuse. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(6):17l02253.

To share: https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.17l02253

© Copyright 2018 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Please sign in or purchase this PDF for $40.00.

Save

Cite