Weight gain from medication is one of the most problematic adverse effects facing patients with serious mental illness, says the author of a new JCP study that compared the metabolic effects of 11 different antipsychotics in people with schizophrenia.

“It can be a real barrier in getting people to take their meds,” said corresponding author Michel Sabé, MD, of the Division of Adult Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland.

To understand which of the drugs resulted in the most widening of waistlines, Sabé and his colleagues reviewed data from 52 randomized controlled trials that used fixed doses of either first- or second-generation antipsychotics. Their meta-analysis captured data from 22,588 individuals and focused specifically on dose response.

Psychotropic Drugs With Long Half-Lives

Emerging Treatments in Schizophrenia

By identifying different results along a curve, the researchers were able to depict the effects of each antipsychotic on body weight. This comparison, they said, could prove useful to clinicians, helping them choose the most appropriate medication and dose for their patients.

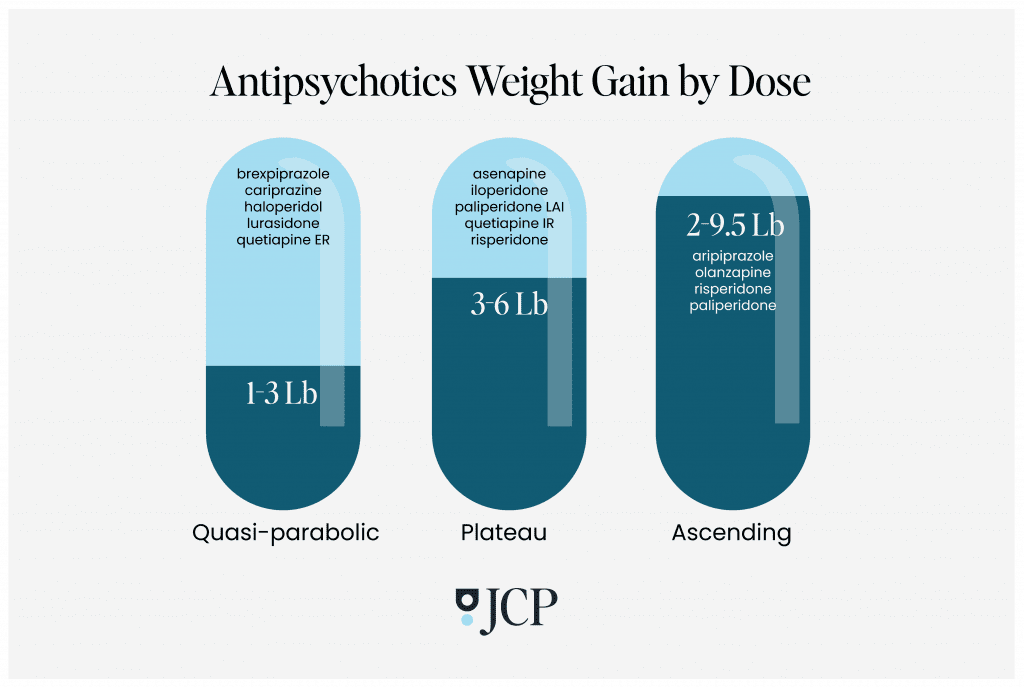

The analysis revealed three different shapes of dose-response curves:

Quasi-parabolic: Antipsychotics along this curve–including brexpiprazole, cariprazine, haloperidol, lurasidone, and quetiapine ER–caused an initial weight gain at a relatively low dose and increased with increasing doses. But at a certain point, the numbers on the scale stabilized, even at higher doses. Except for quetiapine, the authors said that these drugs should be considered “metabolically neutral” with low weight gain (one to three pounds) and minor metabolic disturbances compared to other antipsychotics.

Plateau: With the drugs in this group, there was a dose above which weight gain did not increase any further; weight did increase up to a certain point, but after that, adding more of the drug did not lead to an increase of any additional pounds. The average weight gain from these medications–including asenapine, iloperidone, paliperidone LAI, quetiapine IR, and risperidone–ranged from three to nearly six pounds. Even at very low doses, quetiapine was associated with significant metabolic alterations, they found.

Ascending: In this last group, weight gain continued to climb with each increasing dose, with an average gain from two to nearly 9.5 pounds. The drugs on this curve included aripiprazole, olanzapine, risperidone, and paliperidone, in both oral and long-acting injection forms. Aripiprazole resulted in the least weight gain while olanzapine caused the most. Of note, the authors speculated that these drugs may be more effective at addressing psychiatric symptoms at lower doses, thus minimizing the risk of metabolic side effects.

Sabé explained how antipsychotics stimulate appetite, especially the drive to consume highly caloric foods.

“It seems that ghrelin has an orexigenic role that is directly implicated in antipsychotics-induced weight gain,” he said. “Second generation antipsychotics can act on ghrelin secretion and therefore increase appetite. Several other hormones are also implicated, as is some gene expression.”

Some antipsychotics, such as olanzapine and clozapine, presented the worst profiles and can ultimately send patients down a path towards metabolic syndromes, Sabé said. Lurasidone may offer the best case scenario, he added. However, this prescription may come at the cost of less efficacy on positive symptoms.

Despite the limited number of available studies, Sabe said the study’s findings provided useful clues on how adapting antipsychotic dose relates to weight gain side effects. Further study will determine whether or not the extra adipose related to antipsychotic use can be mitigated or reversed, he said.

“Results from a real-world cohort, with follow-up of patients that continue antipsychotic use, might bring us more impactful information,” Sabé said.

Finally, since use of these medications is often part of a long-term maintenance treatment program, prevention strategies should be considered at the outset, especially for women who appear more vulnerable to putting on weight, Sabé advised.

“Factor in non-pharmacological interventions like healthy diet, nutritional counseling, regular physical activity and use of cognitive and behavioral strategies. In the presence of a metabolic syndrome, consider the use of metformin to improve insulin resistance, or sibutramine to decrease lipid levels,” he said.

Review the full The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry study results here.