Psychiatrists who specialize in treating individuals with psychosis face numerous challenges, including determining when and how to discontinue antipsychotic medication. A recent study published in Molecular Psychiatry shed light on this matter by investigating brain network biomarkers in rehabilitated psychosis patients to understand how they influence recovery. The findings offer valuable insights that can inform clinical practice and enhance treatment decision-making.

Earlier Use of LAI Paliperidone Palmitate Versus Oral Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia

Risk of All-Cause and Suicide Death in Patients With Schizophrenia

Weight Gain Concerns For Patients On Antipsychotic Medications

Key Findings

The study involved 30 patients who had recovered from psychosis and discontinued antipsychotic medication, alongside 50 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. The study further divided recovered patients into two subgroups: those who relapsed after discontinuing antipsychotics and those who sustained their recovery without relapse.

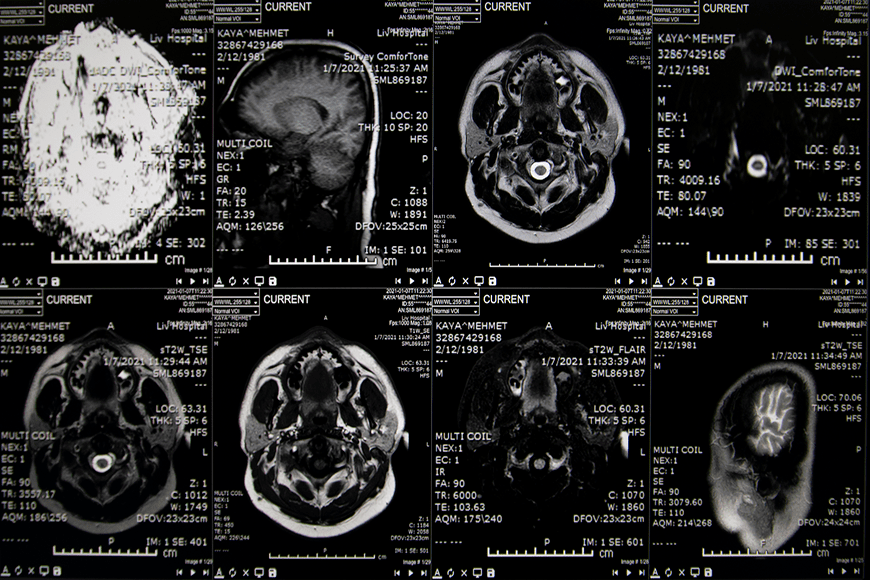

Using resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) and graph theory analysis, the researchers assessed the topological organization of the functional brain “connectome.” The connectome is a nervous system composed of neurons which communicate through synapses. It serves as a complex blueprint for the interconnections between brain regions and plays a critical role in shaping behavior, cognition, and emotional responses.

The brain networks of patients who were fully recovered were operating about the same as those of healthy individuals, but with some important differences.

Recovered brains demonstrated stronger overall brain connectivity and more connections between different brain regions compared to the healthy individuals. Their brain networks were more active and interconnected which suggests that, even in a state of recovery, persistent alterations in brain connectivity remained.

The most notable variances were between the brains of patients in the two subgroups. Relapsed patients showed lower global efficiency compared to patients who stayed off medications, meaning their brain networks were not operating at peak performance. The average number of connections it took for a signal to travel between two brain regions, a concept known as characteristic path length, was longer for those who relapsed. Their brain networks were less robust as well, leaving them more vulnerable to disruptions or changes.

Additionally, specific brain regions, known as hubs, correlated with better cognitive functioning in patients who sustained their recovery from psychosis. The “degree centrality” of these hubs, a measure of their importance within the brain network, also correlated with enhanced cognitive functioning in patients who sustained their recovery.

Clinical Implications

The sample size of this study was small, largely because the researchers had difficulty recruiting subjects who fit their criteria. But it offers the first glimpse at how incorporating network biomarkers and connectivity measures into clinical decision-making could facilitate personalized treatment approaches. The researchers said that divergences in brain networks could act as crucial markers for predicting relapse likelihood after medication cessation.

Psychosis affects approximately 3-5 percent of the population at some point in their lives. Schizophrenia, a specific psychotic disorder, affects about one percent of the global population. Other psychotic disorders, such as schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder with psychotic features, also contribute to the overall prevalence of psychosis. Using these biomarkers to identify patients at higher risk of relapse could help clinicians pinpoint which treatments work best for each individual and why. It may someday guide more nuanced decisions in medication management and individualized support plans.