For a while now, scientists have suspected some kind of link between poor psychological well-being and higher dementia risk. What’s been harder to pin down is what changes are happening to one’s psychological health throughout mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia.

“Individuals diagnosed with dementia often have difficulties in adapting adequately to situation changes, establishing new objectives, and maintaining previous relationships with others, which could influence their psychological well-being,” the authors write. “To date, only one study has assessed changes in purpose in life before and after the development of cognitive impairment, showing that purpose in life declined significantly before the onset of cognitive impairment and declined at a much faster rate thereafter.”

Methodology

This study, which relied on data culled from Rush University’s Memory and Aging Project (MAP), sought to plot the trajectories of psychological health before and after an MCI or dementia diagnosis in older adults.

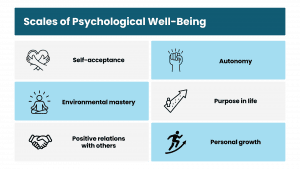

The researchers tracked 910 cognitively intact older adults for as long as 14 years. The research team evaluated each of the participants every year for MCI and dementia. At the same time, they gauged their psychological well-being with Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-Being.

The study’s authors then used mixed-effect models to break down the data, with a focus on changes in psychological well-being before and after the onset of MCI and dementia.

Results

The findings showed that participants who developed MCI suffered a more rapid decline in psychological well-being compared to the control group. This drop appeared roughly two years before the MCI diagnosis.

Among the six components of psychological well-being, the researchers found that “purpose in life” and “personal growth” appeared to be much lower in those who later developed MCI.

More specifically, the researchers noticed that purpose in life started to wane about three years before an MCI diagnosis. And they observed that personal growth started to fall off as early as six years before.

Notably, the rate of decline in psychological well-being didn’t change significantly after diagnosis, which suggests that the deterioration in well-being might begin long before the clinical onset of cognitive impairment.

Additionally, the authors saw an accelerated decline in “positive relations with others” following the MCI diagnosis. And this crumbling of social connections could reflect the challenges those with cognitive impairment face in maintaining relationships and engaging in social activities.

Moving Forward

The study highlights the importance of psychological well-being as a potentially important early indicator of cognitive decline. And lower levels of purpose in life and personal growth could serve as early warning signs of impending cognitive impairment.

The findings suggest implementing interventions that target a patient’s psychological well-being before noticeable cognitive decline begins. The results also underscore the need for continued psychological support for MCI and dementia patients, since their well-being will probably keep deteriorating.

This study adds to already mounting evidence linking psychological well-being and cognitive health. These results seem to suggest that certain aspects of well-being could be more sensitive to cognitive decline than others.

Finally, a better understanding of the biological and psychological mechanisms at play here could help caregivers design and deliver more targeted and effective interventions. For example, exploring the role of inflammation, cardiovascular health, and social engagement could offer new avenues for prevention and treatment.

“Further research is needed to investigate whether and to what extent interventions targeting these well-being components may benefit cognitive function and help prevent the development of dementia,” they wrote.

Further Reading

Lancet Commission Identifies 2 New Modifiable Dementia Risk Factors

Research Helps Clear Up Confusion About Cognition

Cognitive Decline Threatens Financial Stability of Older Americans