Robert Card, the U.S. Army reservist who killed 18 people and injured 13 in November In Lewiston, Maine, suffered from a traumatic brain injury. Two days later, authorities found Card dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

The Maine Office of the Chief Medical Examiner contracted with Boston University’s CTE Center to examine the shooter’s brain as part of its autopsy report. Card’s then family released the results to the public through the Concussion Legacy Foundation.

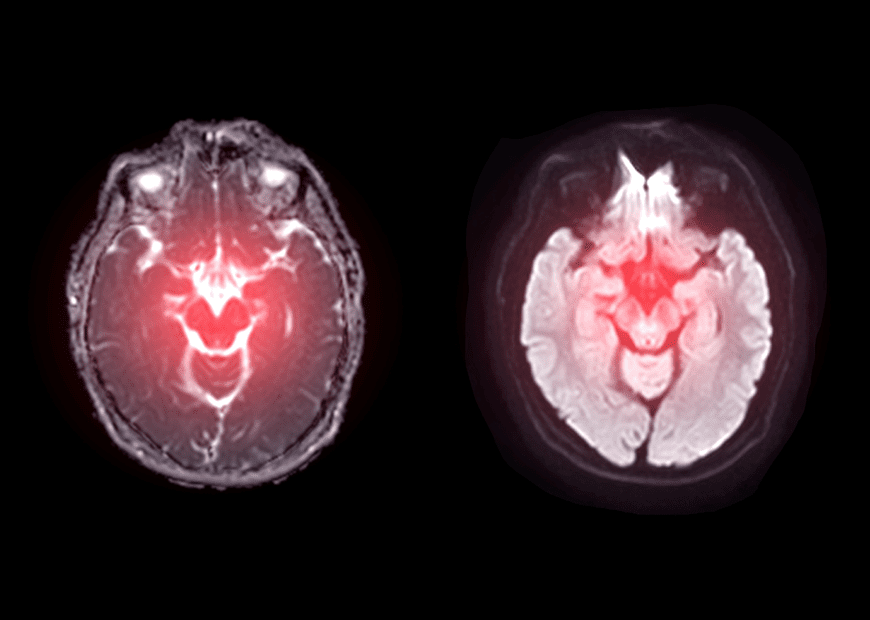

“Robert Card had evidence of traumatic brain injury,” BU CTE Center Director Ann McKee, MD announced. “In the white matter, the nerve fibers that allow for communication between different areas of the brain, there was significant degeneration, axonal and myelin loss, inflammation, and small blood vessel injury. There was no evidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). “These findings align with our previous studies on the effects of blast injury in humans and experimental models. While I cannot say with certainty that these pathological findings underlie Mr. Card’s behavioral changes in the last 10 months of life, based on our previous work, brain injury likely played a role in his symptoms.”

Exposure to Low-Level Explosions

Card worked as an instructor at a hand grenade training range. And that’s where he received exposure to thousands of low-level blasts over eight years. Family members reported that he’d expressed thoughts of paranoia and spoke of hearing voices in 2023. And he’d already suffered some hearing loss.

Maine State Police reported that on Oct. 22, Card drafted a note on his cellphone, confessing to “having issues,” and “he’s had enough and he’s trained to hurt people.”

The Army subsequently released a statement that read, “The Army is committed to understanding, mitigating, accurately diagnosing and promptly treating blast overpressure and its effects in all forms. While prolonged blast exposures can be potentially hazardous, even if encountered on the training range and not the battlefield, there is still a lot to learn.”

An Authority In Brain Injuries

The BU CTE Center has a reputation for its research on brain injuries. As recently as February, researchers at the center published a report that revealed “the most definitive evidence to date that CTE p-tau pathology is primarily responsible for cognitive and functional symptoms, up to 49% of the variation seen in individual patients.”

“For the first time, we were able to show a clear dose-response relationship between the amount of CTE pathology and the severity of cognitive and functional symptoms, including problems with memory and executive function,” explained co-author Jesse Mez, MD, MS, co-director of clinical research at the CTE Center and associate professor of neurology at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. “These findings provide a clear step forward toward diagnosing CTE in life.”

These findings, published online in Molecular Neurodegeneration, revealed a link between the amount of p-tau pathology across the brain – primarily in the frontal lobe– and more cognitive and functional symptoms. The researchers also tied the frontal lobe p-tau pathology to neurobehavioral symptoms.

But, those neurobehavioral symptoms failed to highlight a connection to cognitive symptoms. P-tau pathology explains 14% of the variation in neurobehavioral symptoms.

The study’s authors added that this discovery offers a better understanding of diagnosing CTE while patients are still alive.

“Diagnosis is crucial before we can test therapies. With validated in-life diagnostic criteria, we will be able to design clinical trials for therapies,” Mez explained.

Further Reading

Firearm Storage Practices Among Military Service Members With Suspected TBI