Despite advancements that have turned childbirth into a (mostly) routine procedure, U.S. maternal mortality rates are creeping up.

The U.S. maternal mortality rate for 2021 was 32.9 deaths per 100,000 live births. That’s a disturbing jump from rates of 23.8 in 2020 and 20.1 in 2019, according to the latest data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That’s tragic enough on its own. But for Black women, the maternal mortality rates skyrocketed to 69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births. That’s 2.6 times the rate for non-Hispanic White women (26.6).

But Why?

A research team, led by Children’s National Hospital, wanted to find out why. So the group pored over years of data. And they found that mental illness might be behind the startling rise in the mortality rate. The group looked through 30 peer-reviewed studies and more than a dozen health policy publications.

JAMA Psychiatry published the results of this research in their latest edition.

“The contribution of mental health conditions to the maternal morbidity and mortality crisis that we have in America is not widely recognized,” study co-author Katherine L. Wisner, MD, explained in a press release. “We need to bring this to the attention of the public and policymakers to demand action to address the mental health crisis that is contributing to the demise of mothers in America.”

Startling Maternal Mortality Statistics

The review painted a disturbing landscape:

- Medical professionals could prevent more than 80 percent of U.S. maternal deaths.

- The researchers tied almost one in four maternal deaths directly to mental health disorders.

- Overdose – along with other maternal mental health conditions – ends the lives of more than twice as many women as postpartum hemorrhage, the second leading cause of maternal mortality.

Worse still, the researchers found that despite federal and state investments meant to stem the tide of maternal death – including more than $100 million in state programs to improve maternal health access – it has so far failed to curb “the public health crisis that it represents.”

Other highlights of the research review include:

- Multiple studies show that the perinatal period subjects women to a higher risk of psychiatric disorders. More than 14 percent of pregnant mothers admit to a new episode of depression. Another 14.5% develop an episode within 90 days of birth.

- More than 400 maternity healthcare centers across the United States shut their doors between 2006 and 2020. This led to what the researchers dubbed “maternity care deserts,” which left nearly 6 million women with limited to no maternity care access.

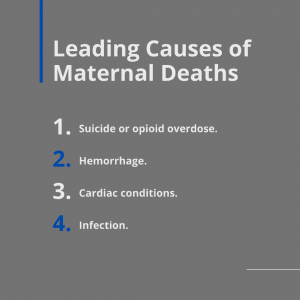

- Mental health conditions such as suicide or opioid overdose were responsible for nearly 23% of maternal deaths. That’s followed by hemorrhage (13.7%), cardiac conditions (12.8%), and infection (9.2%).

Researchers Push for New Priorities

Wisner, associate chief of Perinatal Mental Health and member of the Center for Prenatal, Neonatal & Maternal Health Research at Children’s National, adds that medical professionals only screen about 20 percent of new mothers for postpartum depression.

“Given that this is a time that many mothers have contact with healthcare professionals, it’s critically important that all mothers are screened and offered treatment,” she said. “Mental health is fundamental to health — of the mother, the child, and the entire family.”

The researchers argue that policymakers must consider a fundamental shift in how they approach maternal health. For example, the authors push for paid parental leave of at least 2 to 3 months.

“Instead of focusing on a relatively minor portion of the contributors to health that current medical practice targets, fortifying the social foundation strengthens the prospects for the future health of families through culturally relevant, patient-centered care,” the study authors concluded. “It is past time to embrace this conceptual shift to embrace health writ large. Mental health is fundamental to health.”

Further Reading

Prevalence and Correlates of Perinatal Self-Harm

Treating Comorbid Perinatal Depression and PTSD in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Women