For the first time ever, scientists can see which parts of the brain light up during episodic and chronic migraine without aura.

The findings, which will be presented next week at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA), revealed significant changes in the perivascular spaces of a brain region called the centrum semiovale.

“These changes have never been reported before,” said study co-author Wilson Xu, an M.D. candidate at Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Up to 148 million people – 39 million in the U.S. – are affected by migraine, the American Migraine Foundation says. Beyond a crushing headache, migraine is often accompanied by nausea, fatigue and light sensitivity. People with chronic migraine have more than 15 headache days a month for at least three consecutive months. If someone has fewer than 14 headaches per month on average, they are diagnosed with episodic migraine.

Perivascular spaces are fluid-filled pockets surrounding blood vessels in the brain. They are most commonly located in the basal ganglia and white matter of the cerebrum, and along the optic tract, the report noted. Perivascular spaces are affected by several factors, including abnormalities at the blood-brain barrier and inflammation. Enlarged perivascular spaces can be a signal of underlying small vessel disease.

“Perivascular spaces are part of a fluid clearance system in the brain,” Xu said in a press release. “Studying how they contribute to migraine could help us better understand the complexities of how migraines occur.”

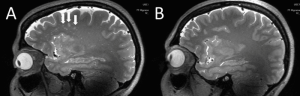

To view what’s going on in the brain, the researchers used ultra-high-field 7T MRI to compare structural microvascular changes in different types of migraine. Because 7T MRI is able to create neurological images with a higher resolution and better quality than other MRI types, it can spot nuances that happen in brain tissue after a migraine, they noted.

White matter hyperintensities, which are lesions that “light up” on MRI, were measured using the Fazekas scale. Cerebral microbleeds were rated with the microbleed anatomical rating scale. The researchers also collected clinical data such as disease duration and severity, symptoms at time of scan, presence of aura and right-or-left side of headache. Study subjects included 10 with chronic migraine, 10 with episodic migraine without aura, and five age-matched healthy controls; subject age ranged from 25 to 60.

Association Between Computer Vision Syndrome, Insomnia, and Migraine

Common Themes of Patient Experiences With Migraine

Statistical analysis discovered that the number of enlarged perivascular spaces in the centrum semiovale was significantly higher in patients with migraine compared to the controls. Additionally, enlarged perivascular space quantity in the centrum semiovale correlated with deep white matter hyperintensity severity in migraine patients.

The researchers hypothesize that changes in the perivascular spaces in patients with migraine might suggest a glymphatic disruption within the brain. The glymphatic system is a waste clearance mechanism that uses perivascular channels to help eliminate soluble proteins and metabolites from the central nervous system.

However, this trial did not answer the question about whether or not the changes viewed on MRI affect migraine development or results.

“The results of our study could help inspire future, larger-scale studies to continue investigating how changes in the brain’s microscopic vessels and blood supply contribute to different migraine types,” Xu said. “Eventually, this could help us develop new, personalized ways to diagnose and treat migraine.”