A rare case of a live worm in the brain demonstrates what happens when parasites invade the central nervous system.

A Mysterious Presentation

In a case study published in the September issue of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s journal, Emerging Infectious Diseases, doctors describe a 64-year-old woman living in southeastern Australia who developed a perplexing array of symptoms over the course of a year. It began with abdominal pain and diarrhea, followed by a dry cough and night sweats.

Doctors initially diagnosed her with community-acquired pneumonia. However, even after antibiotic treatment, her symptoms failed to resolve.

Youngest Ever Case of Dementia Diagnosed

Brain Atrophy in First-Episode Psychosis of the Elderly

Catatonia and Competency to Stand Trial

Further testing revealed abnormalities such as high levels of eosinophils, a type of white blood cell that combats parasitic infections. She also developed lesions in her lungs, liver, and spleen, as well as migrating lung opacities.

Biopsies only deepened the mystery. They indicated eosinophilic pneumonia but without any obvious cause. Doctors hypothesized she might have a hematologic cancer or autoimmune disease. They began treating her with steroids and chemotherapy.

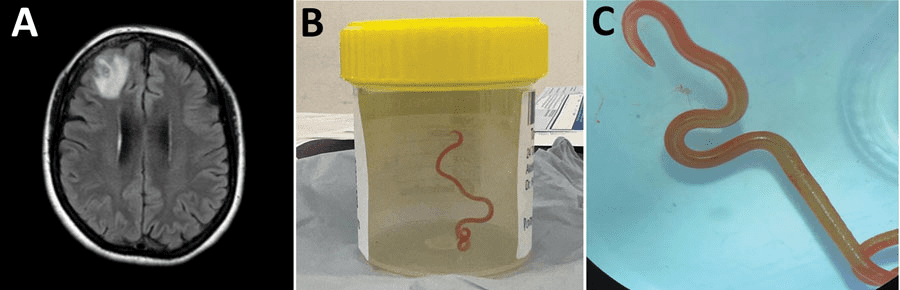

Despite aggressive treatment, neurological symptoms emerged. She experienced progressive forgetfulness and worsening depression. Brain imaging identified a lesion in her right frontal lobe.

The Surprising Diagnosis

Only during surgery to biopsy this lesion did physicians discover the true culprit–a live, 80mm (approximately three inch) nematode worm wriggling its way through her brain tissue. Subsequent PCR sequencing identified the worm as Ophidascaris robertsi, a parasite not previously known to infect humans.

“O. robertsi” uses pythons as its definitive host, the authors said. It spreads its eggs through the snake’s feces. This patient likely ingested the eggs while collecting Warrigal greens, also known as New Zealand spinach, for cooking near her home, which was close to an area populated by pythons.

Once inside a mammalian host, O. robertsi larvae can migrate throughout organs, provoking an intense immune response. This woman’s eosinophilia and migrating lesions appeared to be her body’s reaction to the parasite intruding upon her tissues.

Neural larva migrans, as the invasion of larval worms into the central nervous system is known, is quite rare. The report noted that there are only around 700-800 cases per year globally across all worm species that can cause this condition. Toxocara species such as roundworms are the most common culprit.

Symptoms of parasitic brain invasion depend on the location but may include seizures, weakness, or neuropsychiatric disturbances. The diagnosis is challenging given the parasite’s obscurity.

Ongoing Treatment

Once the live O. robertsi larva was surgically removed from the patient’s brain, the patient received a two-day course of ivermectin, an anti-parasitic medication that can kill nematodes and larval worms. This was followed by four weeks of albendazole, another agent active against a broad range of helminth infections.

To manage inflammation, the patient was also started on a tapering course of dexamethasone over 10 weeks. All other immunosuppressive medications the patient had been taking for presumptive diagnoses like cancer were discontinued after the parasite was extracted.

Three months after completing the steroid regimen, the patient’s blood eosinophil count had normalized, suggesting successful treatment of the infection. Some residual neuropsychiatric symptoms persisted but had improved from her presentation prior to worm removal. The authors of the paper said they will continue to monitor her, noting that brain parasites can stay hidden, sometimes lingering for years.

A Unique Case

This Australian woman represents the first documented O. robertsi infection in humans. According to the authors, climate change may be expanding the range of pythons and other definitive hosts, bringing humans into closer contact with the parasites they harbor. Though uncommon, the authors advised that infections like neural larva migrans must be considered as a differential diagnosis when patients present with migrating organ lesions and neurological symptoms.

“In summary, this case emphasizes the ongoing risk for zoonotic diseases as humans and animals interact closely. Although O. robertsi nematodes are endemic to Australia, other Ophidascaris species infect snakes elsewhere, indicating that additional human cases may emerge globally,” they warned.