With the rise of psychology apps, therapy is now just a few clicks away for the masses. But there are few guidelines to ensure that digital mental health services are safe, effective and private.

A new consensus paper aims to change that. Published in Nature Mental Health, the guideline establishes an ethical roadmap for companies providing internet-based mental health assistance. The 25 international experts and a think tank contributing to the report aim to address potential pitfalls in research and care, providing practical recommendations ranging from intervention development to clinical implementation.

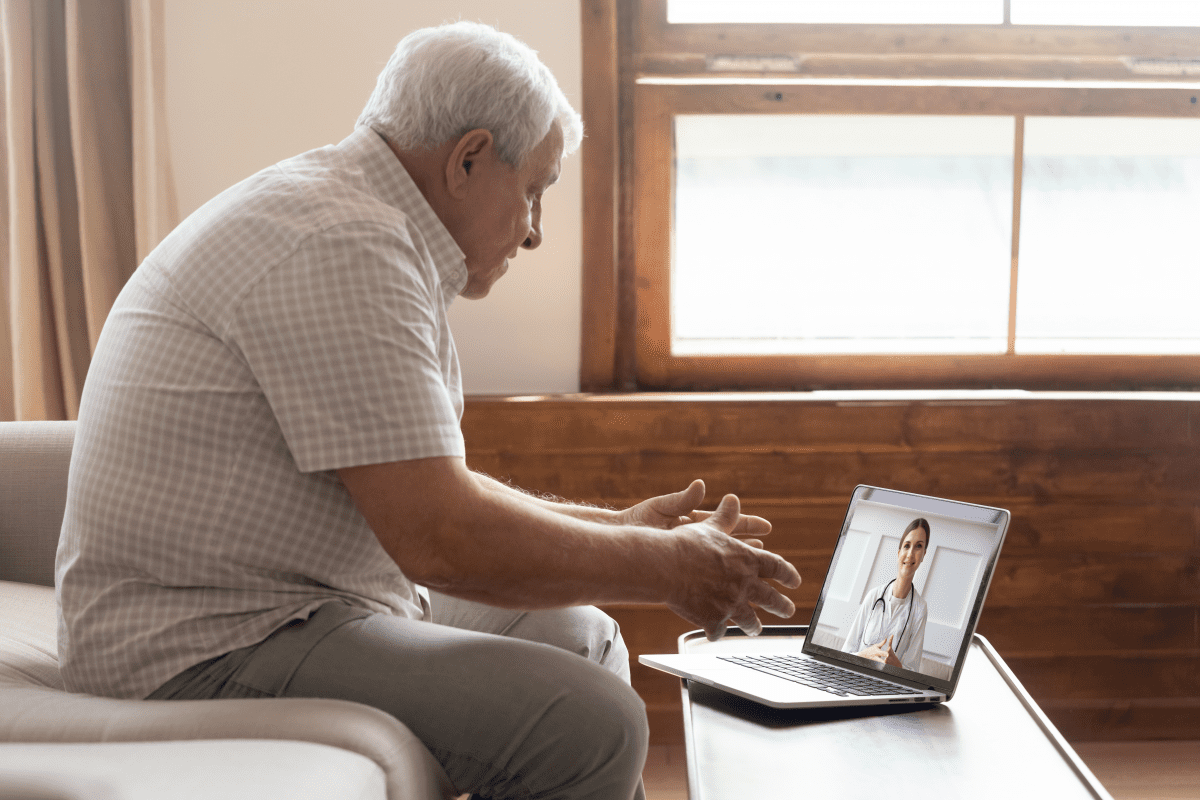

Use of Technology in the Clinical Care of Depression

User Perception of Telephone-Based Telepsychiatry Consultation

Singer-Songwriter’s Raw Depictions of Mental Health Strike a Chord

“In this Consensus Statement, we aim to provide current practical guidelines for researchers and practitioners in the field of e-mental health to cover the most important topics of the development, deployment and evaluation of e-mental health assessments and interventions,” the researchers wrote.

The recommendations generally fall into four major buckets.

Participatory Design

Shaping digital tools without involving users can breed apps devoid of purpose or strayed tech, caution the researchers. They urged embracing participatory design. That is, programs that actively engage end users like patients, clinicians, and caregivers early and often. Focus groups, interviews, and usability testing give target populations an opportunity to shape interventions that address real-world needs and integrate seamlessly into overall care.

The researchers stressed the importance of maintaining a “human-centered” process to ensure digital mental health solutions evolve organically from user insights.

“Developers should see themselves as partners, rather than authoritative experts, embracing participatory research approaches,” they wrote.

Managing Risks

Well-intended tools like depression apps require meticulous risk management planning. Suicidality and privacy violations specifically demand vigilance. That means researchers must implement suicide assessment protocols and crisis response systems.

They write, “Excluding suicidal patients or those with other risk factors from e-mental health interventions prevents deliverance of support when potentially most needed and excludes a large number of patients that could benefit from low-threshold services.”

The authors contend that excessive exclusion denies care to numerous high-risk patients who could benefit from digital mental health tools. But firm safeguards could expand access among underserved groups. Likewise, mandatory informed consent and data encryption for personal health data collection could help ease patients who worry about the security of the intimate details they share.

Hybrid Research Methods

Digital health warrants creative evaluation beyond clinical trials.

“While randomized controlled trials are essential for establishing efficacy, a diversity of complementary research approaches should be employed to gain a comprehensive understanding of whether and how an intervention works,” they pointed out.

Among their recommendations: Mixed methods to enrich the understanding of whether apps work. Ethnography, surveys, and interviews to capture user perspectives. Observational designs to study real-world effectiveness. N-of-1 trials for personalize treatments. And analytics to reveal usage patterns. Blending these approaches with rigorous trials would provide a comprehensive lens for sharpening e-mental health interventions, the researchers said.

Responsible Implementation

“Clinicians need to receive extensive training to successfully integrate digital health into their practice,” the researchers wrote. “The goal should be seamless workflow integration, with technology supporting rather than challenging the provider’s expertise.”

To this end, the researchers stressed that apps should augment clinicians’ expertise, not engender mistrust. Throughout the entire implementation process patient needs must come first. Even the best app is meaningless without compassion, they wrote, noting that while tech, including artificial intelligence (AI), can enhance human relationships it can’t replicate them. That’s why implementation priorities should focus on better care and outcomes – not cost-cutting.

The Bottomline

Although the paper refrains from an explicit definition, ‘e-mental health’ envelops a realm of technologies – websites, mobile apps, wearables, and social platforms – that deliver vital mental health services and interventions. This includes services like online counseling, digital cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) programs, mental health chatbots, mood tracking apps, and automated sensing technologies. The “e” denotes the electronic aspect at the core of these offerings.

Contributing experts hail from a variety of backgrounds. The panel included psychiatrists, psychologists, and computer scientists spanning various areas including clinical studies, tele-psychotherapy, mental health state assessment, intervention, app development, and AI. Additionally, they represented diversity in research experience, culture, and gender.

The experts emphasized that the guidelines provide a starting point, a guiding compass for best practices in digital mental health that currently doesn’t exist. They urge the e-mental health community to collaborate on scientific rigor and innovation, with ongoing reevaluation and updates.

“In sum, this expert consensus aimed at promoting the quality of technical innovations and at responsibly implementing these in the healthcare system. We provided a first comprehensive essence of scientific knowledge and practical recommendations for e-mental health researchers and clinicians.”