Anyone who spends time in New York City can plainly see there is a homeless crisis, one that has grown exponentially worse since the start of the pandemic nearly three years ago.

The number of people who live on the streets and subways in the country’s largest city has risen to its highest levels since the Great Depression of the 1930s, says the advocacy group Coalition for the Homeless. In September of 2022, the organization recorded 60,252 homeless people, including 19,310 children, sleeping each night in New York City’s municipal shelter system.

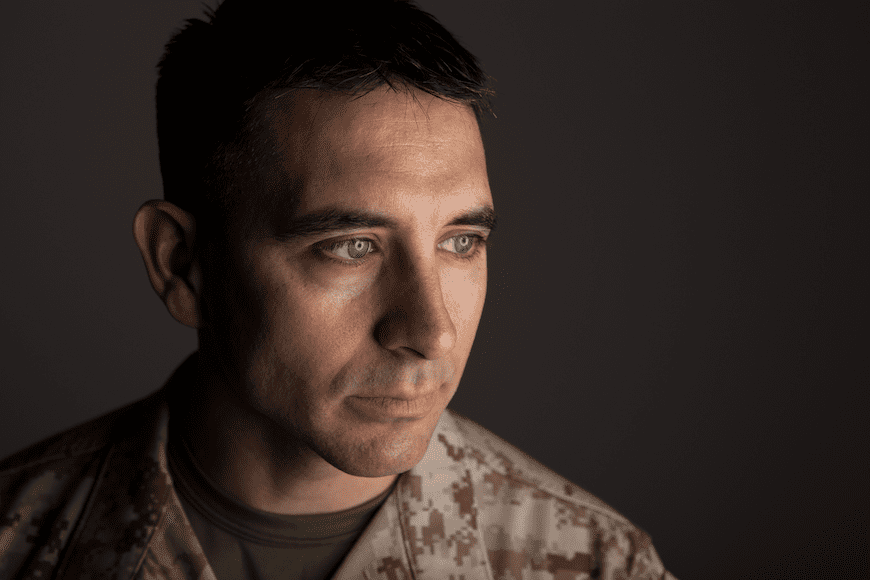

Homelessness, and Other Societal Outcomes Among US Veterans With Schizophrenia Relapse

A Systematic Review of Experimental Trials of Mental Health Treatment Interventions

Homelessness in the Child and Adolescent Population

This week, Mayor Eric Adams said he would address the issue head on by directing police and city medics to place severely mentally ill people into treatment, even if they refuse care.

“These New Yorkers and hundreds of others like them are in urgent need of treatment, yet often refuse it when offered,” the mayor declared at a news conference. “No more walking by or looking away.”

Those suffering from severe mental illness have more than a right to exist or survive. They have a right to healthcare, housing, and treatment. A right to dignity and respect. A right to safety and security.

Read more: https://t.co/9ZECnw2ZNw pic.twitter.com/MK3CHA2XmI

— Mayor Eric Adams (@NYCMayor) November 29, 2022

Adams said he is basing the new directive on the city’s “Kendra’s Law,” which allows the courts to order defendants with mental illness to complete treatment. The 1999 law was named after Kendra Webdale, who died after being pushed onto the subway tracks by a man with a history of mental illness.

New York state places limits on forcing someone into mental health treatment against their will, but Adams says his new policy will address the myth that a person must exhibit outrageously dangerous or suicidal behavior before authorities can take action. He also stressed that police and other officials implementing the policy will be connected to a hotline manned by professional mental health clinicians who can offer them advice on a case-by-case basis.

Reaction to Adam’s Proposal

Not all homeless and civil rights advocacy groups welcomed the new plan.

“Forcing people into treatment is a failed strategy for connecting people to long-term treatment and care,” Donna Lieberman, executive director the New York Civil Liberties Union told the New York Times. The Coalition for the Homeless expressed similar views.

However, Jeffrey Berman, an attorney for the mental health unit of the Legal Aid Society, expressed cautious support for the mayor’s plan.

“We agree with the spirit of Mayor Adams’ address, which, you know, very much centers around confronting this human problem with compassion and sensitivity,” Berman told the New York Times. He added that the criminal legal system needed to find solutions for people who do end up arrested to move into treatment and recovery rather than jail.

Psychiatrist Helen Riess, MD says she sees both sides of the argument. Riess is the associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of empathy research and training at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“I think that offering help and mental health services and places to live is an amazing first step,” Riess said. “But it has to be done with empathy for the person and not come down as people feeling forced to do something against their will.”

The Pros and Cons

Riess said that most people living in homes can’t imagine that anybody would actually make the choice to stay on the street. But some people with mental illness don’t immediately accept the resources being offered to them and may view a helping hand with fear, suspicion, and paranoia.

“This is not like flipping a switch where all of a sudden everybody’s going to feel grateful and go along with new housing or treatment opportunities. So, my caution about this well-intentioned idea is to remember that all human beings are unique and they have unique reasons for being homeless and unique reasons for either being ready to accept mental health care or not.”

If the New York program is too aggressive, Riess is concerned that it could backfire.

“Some of the most severely mentally ill people could feel violated by being forced to go somewhere against their will. And I think it takes a real understanding of mental illness with people who are trained in how to talk to very mentally ill people and to approach them with the kind of care and tentativeness that is required to start building trust.”

The State of Homelessness in the US

One thing everyone seems to agree on is that homelessness has become a pervasive problem in the US. In 2020, the last year homelessness data was collected due to interruptions by the pandemic, the National Coalition to End Homelessness reported that 580,466 people experienced homelessness in America. Most were individuals (70 percent) and the rest were families with children.

Met with NY Coalition for the Homeless today to talk about the problems facing the population as we come out of the pandemic. Check out their comprehensive State of Homeless report for 2021 focusing on Housing as Healthcare. https://t.co/ZHs1jDNyYl pic.twitter.com/N6jRquJqnc

— National Coalition for the Homeless (@NationalHomeles) May 4, 2021

Homelessness exists in every state in the nation, with people often forced out of housing due to the high costs, joblessness, inaccessibility to mental health resources, and safety net programs that are strained to the breaking point. California currently has the highest number of homeless, with about 151,278 people without a place to live, according to World Population Review. This represents nearly 20 percent of the total homeless population in the country.

New Yorkers do want to see the problem addressed. More than 70 percent said they feel that as long as homelessness exists, we are not living up to our values as a country, according to a recent survey by the group, Win. Nearly 90 percent think tax dollars that help the homeless are well spent.

“This is a profound blight on our society because you don’t walk into every city in the world and see people on the streets,” Riess said. “There will always be people who are incapable of taking care of themselves and how we choose to help them says a lot about who we are.”