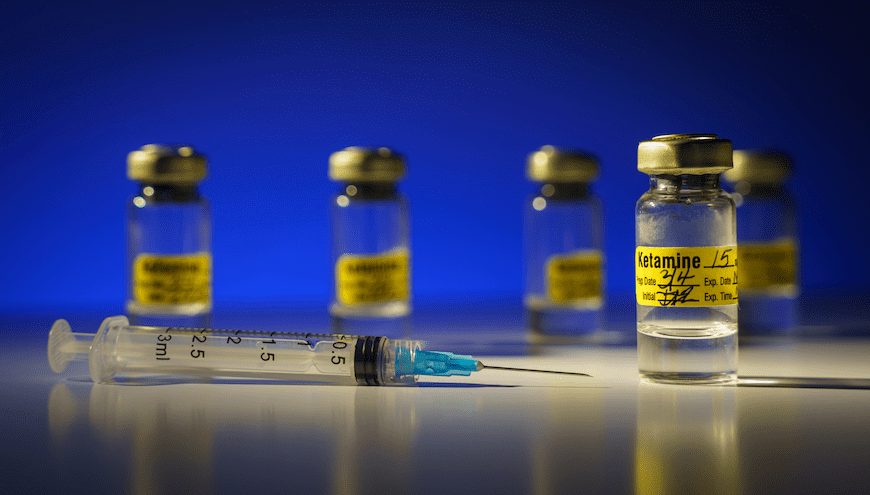

In the former CNN anchor’s first (and last) interview for the social media giant X, Don Lemon asked X owner Elon Musk about his experience with ketamine.

“There are times when I have sort of a … negative chemical state in my brain, like depression I guess, or depression that’s not linked to any negative news, and ketamine is helpful for getting one out of the negative frame of mind,” Musk explained.

Musk also pointed out that he has a prescription from “an actual, real doctor.” He added that he uses “a small amount once every other week or something like that.”

The interview refocused the media’s attention on something that those with depression caught on to years ago. One study, for example, showed that U.S. ketamine prescriptions grew from .55 per 100,000 people in 2017 to more than three for every 100,000 in 2022.

As a result, scientists have been taking a more careful look at ketamine – which started life as an analgesic during the Vietnam War.

The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders has published three important research projects this year alone that have helped clarify the drug’s role in treating Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). We’ve put together summaries – and links – to this research for further review.

Pharmacotherapy and Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression

Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) lacks a universally accepted definition but the diagnosis hinges on at least two failed treatments. This paper explores a clinical case illustrating TRD in a patient with a protracted depressive history and limited treatment response, characterized by persistent self-criticism. Such self-criticism can exacerbate depressive symptoms, fostering intense anger, self-doubt, and disapproval. This study also addresses the potential underlying causes of self-criticism and its implications on depression.

The discussion, facilitated by expert clinicians from Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, emphasizes the value of integrating diverse clinical perspectives to address complex cases effectively. Research indicates that TRD poses substantial challenges, with only a minority of patients achieving remission through standard treatments. Factors contributing to TRD include:

- Comorbid physical and psychiatric conditions.

- Specific personality traits that predispose individuals to persistent self-criticism and negative self-perception.

Medical professionals use various pharmacological and neurotherapeutic interventions for TRD management. These can include optimization, drug substitution, combination, augmentation, and neurostimulation techniques like electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Ketamine emerged as a promising novel treatment for TRD, demonstrating efficacy via intravenous, intramuscular, and nasal administration routes.

And there’s been a resurgence of interest in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (PAP), employing substances like ketamine, LSD, MDMA, and psilocybin to induce altered states of consciousness associated with therapeutic benefits.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy involves limited drug sessions accompanied by preparatory and integrative psychotherapy sessions. Ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP) is particularly promising for TRD, providing relief from negativity, promoting communication, and facilitating emotional integration. While the evidence base for KAP remains limited, it presents a novel avenue for exploring treatment-resistant conditions. The paper’s authors insist that further research will elucidate the efficacy and mechanisms of action underlying these innovative treatment modalities.

Is Intravenous Ketamine Better Than Intranasal Esketamine for Treating Treatment-Resistant Depression

The letter to the editor highlights the global burden of depression and the challenges associated with treating treatment-resistant depression (TRD). It discusses various treatment options, particularly focusing on ketamine as a promising alternative. Ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, has shown rapid and sustained efficacy in TRD and suicidal ideation at subanesthetic doses. The FDA approved esketamine, a derivative, for TRD in adults and has shown promising results in clinical trials.

The letter compares the efficacy of intravenous (IV) ketamine and intranasal esketamine. And it covers studies suggesting that IV ketamine could be superior regarding overall response, remission rates, and dropout rates. Despite these results, the FDA still hasn’t approved IV ketamine, possibly because of lingering concerns about side effects.

However, studies indicate a lower dropout rate due to side effects than esketamine.

The authors also express concern about the lack of insurance coverage for ketamine treatment despite FDA approval for esketamine. They argue that advancements in alternative treatments like ketamine could improve clinical management for patients who do not respond to traditional interventions. Moreover, despite the absence of insurance coverage, the use of ketamine could potentially cut costs.

Overall, the letter emphasizes the need for greater consideration of ketamine as a treatment option for TRD. It also suggests that its inclusion could provide better outcomes for patients who do not respond to conventional antidepressants.

Clinical Outcomes of Intravenous Ketamine Treatment for Depression in the VA Health System

The study aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of repeated intravenous ketamine infusions for major depressive disorder (MDD) in routine clinical practice and determine the frequency and number of infusions required to sustain symptom improvement. The researchers examined electronic medical records from the Veterans Health Administration (VA) for patients who received IV ketamine infusions between Fiscal Year 2020 and up to 12 months after their first infusion.

Results from 215 patients showed a mean baseline Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) score of 18.6, with an average of 2.1 antidepressant medication trials in the past year and 6.1 trials over the past 20 years. Infusion frequency decreased from every 5 days to every 3–4 weeks within the first 5 months, with an average of 18 total infusions over 12 months. After 6 weeks, 26% experienced a 50% improvement in PHQ-9 score (response), and 15% achieved PHQ-9 scores ≤ 5 (remission), with sustained improvements at 12 and 26 weeks. Demographic characteristics and comorbid diagnoses did not correlate with 6-week PHQ-9 scores.

The study concludes that while only a minority of patients showed response or remission with IV ketamine, symptom improvements in the first six weeks persisted for at least six months.

However, further research is necessary to determine the optimal infusion frequency and assess potential adverse effects.

Further Reading

Could Scents Crack the Depression Code?

5 Minute Pearls: Ketamine for Treatment Resistant Depression and Suicidal Ideation

Combining Ketamine and Psychotherapy for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder