At a time of year when depression is more likely to ensnare, well, anyone, with the holidays in the rearview and months of cold, dark days still ahead, maybe it’s fitting that new research reveals some promising results with the use of spinal cord stimulation.

A group of University of Cincinnati researchers, operating out of its Lindner Center of HOPE, discovered that not only is non-invasive, spinal cord stimulation effective and feasible, but that it comes with minimal side effects.

Francisco Romo-Nava, MD, PhD, led the groundbreaking study and published the results in the latest issue of Modern Psychiatry.

“We think that the connection between the brain and the body is essential for psychiatric disorders,” Romo-Nava, associate professor at UC’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences told the college news outlet. “Many of the symptoms of mood disorders or eating disorders or anxiety disorders have to do with what one could interpret as dysregulation in this brain-body interaction.”

Exploring the Mood, Spinal Connection

Researchers have long suspected that spinal introspective pathways, “the corticocortical connections and the associated Bayesian active inference interoceptive processes in the brain regulate bodily states through descending projections” and play a vital part in shaping what the researchers call “emotional experience.” As a result, the theory suggests that they influence mood and mood disorders, such as major depressive disorder.

What we call MMD includes “a heterogeneous syndrome with multiple possible neurobiological components (e.g., hyperactive HPA axis and increased sympathetic tone), as well as contributing external factors (e.g., exposure to chronic stress).”

But what most overlook is that MDD doesn’t occur in a vacuum. Sparsely documented but relevant “autonomic and somatic symptoms involving multiple sensory modalities including pain conditions and abnormal body phenomena” back up the authors’ thesis that maybe disjointed interoceptive signaling and processing contribute to disorders like MDD.

Further Reading:

More Evidence Psychedelics Can Curb Depression

Watching TV, Passive Sitting, Linked to a 43% Higher Risk of Depression

The Weekly Mind Reader: Decoding Treatment-Resistant Depression

In short, “these observations suggest that chronically hyperactive/dysregulated efferent pathways and SIPs signaling may lead to anomalous interoceptive processing. Consequently, a dysregulated brain-body circuit may be accessible to neuromodulation-based interventions targeting SIPs at the spinal cord level to explore their role and therapeutic potential in MDD.”

But the extent to which that’s true – and how to leverage that for therapeutic benefits – hasn’t been documented until now.

(Re)connecting the Dots

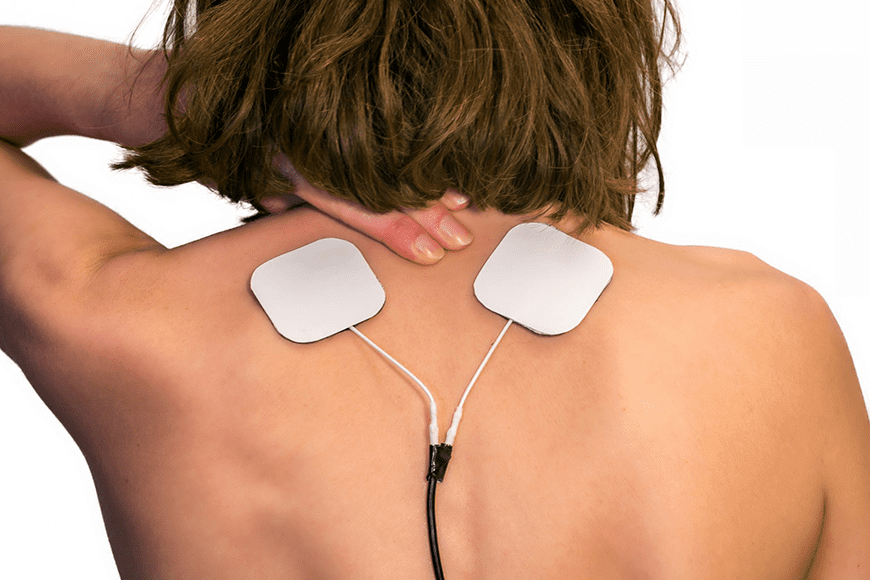

Transcutaneous spinal direct current stimulation (tsDCS) remains a relatively inexpensive and non-invasive way to modulate spinal cord function in patients in an attempt to modulate SIPs. The researchers conducted the electric field (E-field) simulations with electrode montages with the anode at the T10 or T11 and the cathode on the shoulder.

Researchers noted mild side effects, such as temporary skin irritation at the stimulation site and passing itching or burning sensations that didn’t linger beyond the original treatment sessions.

Patients who received the active stimulation experienced some relief, with a notable drop in the severity of MDD symptoms compared to the control group.

But Romo-Vana added that this research needs to be replicated on a much larger scale before we draw any conclusions

“We need to be cautious when we interpret these results because of the pilot nature and the small sample size of the study,” Romo-Vana explained.. “While the primary outcome was positive and it shows therapeutic potential, we should acknowledge all the limitations of the study.”

Study methodology

After four years of recruitment, the researchers conducted the double-blind, randomized study at the Linder Center with 20 participants.

Half of them received an “active” version of the spinal cord treatment, while the other half received a “sham” version. Treatments consisted of 20-minute sessions, conducted three times a week, over eight weeks.