At the risk of throwing cold water on Valentine’s Day, a group of researchers at the University of Toronto Mississauga published a study in the latest issue of Current Directions in Psychological Science that seems to debunk the lingering concept of “love languages.”

In short, the researchers conclude that, “In sum, although popular lay theories might have people believe that there is a simple formula for cultivating lasting love, empirical research shows that successful relationships require that partners have a comprehensive understanding of one another’s needs and put in the effort to respond to those needs. As relationship scientists, our aim is to dispel the notion that there is a simple and straightforward fix for improving relationships.”

Decades of Love Languages

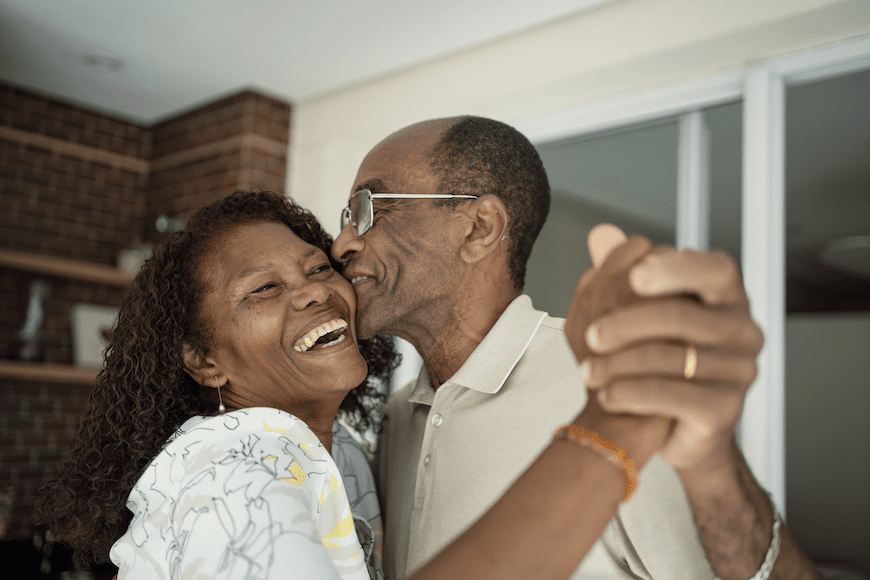

Since Baptist minister Gary Chapman published his treatise, The Five Love Languages: How to Express Heartfelt Commitment to Your Mate in 1992, it gradually accumulated a loyal following – among psychiatric professionals and laypeople alike. In the decade following its release, the book had remained on The New York Times Bestseller List for nearly 300 weeks.

The book’s central conceit is that there are five general ways by which partners express – and want to receive – affection, which Chapman dubs the love languages. They are:

- Words of affirmation.

- Quality time.

- Gifts.

- Acts of service.

- Touch.

Scientific Pushback

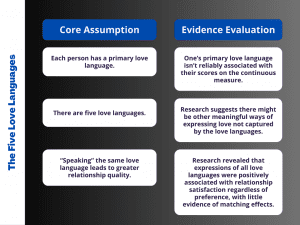

Nevertheless, the Toronto research team writes that “there is a paucity of empirical work on love languages, and collectively, it does not provide strong empirical support for the book’s three central assumptions that (a) each person has a preferred love language, (b) there are five love languages, and (c) couples are more satisfied when partners speak one another’s preferred language.”

After mulling over possible explanations for the widespread public embrace of the love languages concept, the researchers determined that its because it offers a natural metaphor that the average person can relate to.

“We were very skeptical about the love languages idea, so we decided to review the existing studies on it,” explained Emily Impett, a psychology professor in the UTM department who worked with UTM graduate student Gideon Park and York University Assistant Professor Amy Muise. “None of the 10 studies supported Chapman’s claims.”

Impett suggested that the guiding thesis of love languages starts with a flawed premise.

“People determine their primary love language by taking Chapman’s quiz, which forces them to select the expressions of love they find most meaningful,” Impett added. “It could be choosing between receiving gifts or holding hands, for example. These are trade-offs we don’t have to make in real life. In fact, people report that they find all of the things described by the love languages to be incredibly important in a relationship.”

A New Metaphor to Consider

Impett and her team, instead, offer a new way of looking at relationships. Simply put, “love is not akin to a language one needs to learn to speak but can be more appropriately understood as a balanced diet in which people need a full range of essential nutrients to cultivate lasting love.”

“It keeps all expressions of love on the menu and invites partners to share what they need at different times,” Impett explained. “It allows for the fact that people and relationships aren’t static and can’t be categorized into neat boxes.”

Further Reading

Barriers to Loving: A Clinician’s Perspective