Suicide, a largely silent killer, has long capitalized on that reticence to take its toll on U.S. veterans. The numbers, from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, are sobering:

- In 2020, 6,146 veterans took their lives – an average of 16.8 every day.

- That same year, adjusting for demographic differences, the veteran suicide rate was 57.3 percent greater than for non-veteran U.S. adults.

- That made suicide the 13th leading cause of death among veterans overall. But the second-leading cause of death among those under 45.

Finally, according to the American Psychological Association, every one of the 18 million veterans living in the United States remains at higher risk for suicide than the average citizen.

“Arguably the most significant impact, in terms of psychical and emotional well-being, of Iraq and Afghanistan is the psychological consequences of those wars,” University of Memphis psychology professor M. David Rudd told The Washington Post. “We need to do much more about stigma, normalizing care, and communicating the value of that care.”

VA Takes Action on Suicide

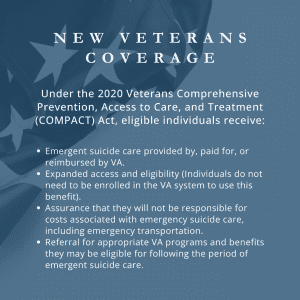

It’s in the shadow of this crisis – only exacerbated by the pandemic – that the VA rolled out a policy in early 2023 that allowed eligible veterans, and some other former service members, in acute suicidal crisis to show up any VA – or non-VA – health care facility and receive free emergency health care. Covered care includes inpatient or crisis residential treatment for up to 30 days and outpatient care for up to 90 days.

In that first year, nearly 50,000 veterans and former service members took the VA up on that offer and received lifesaving care while saving more than $64 million in healthcare costs. The policy also increased access to no-cost emergent suicide care for up to 9 million Veterans. That’s because eligible Veterans don’t need to be enrolled in the VA system or go to a department facility to use this benefit.

“There is nothing more important to VA than preventing Veteran suicide — and this expansion of no-cost care has likely saved thousands of lives this year,” VA Secretary Denis McDonough said in a press release. “We want all veterans to know they can get the care they need, when they need it, no matter where they are.”

Silver Linings, Tarnished Reputation

Even before the VA’s new policy, the veterans’ mental health numbers have been on the rise. From 2019-20, veteran suicide rates dropped almost 10 percent. And whether it’s a statistical blip or a harbinger of a larger culture shift, veterans appear to be more willing to accept help. Despite the 24.6 percent drop in the U.S. veteran population from 2001 to 2020, VA visits are up 55 percent.

But despite this latest success story, the VA struggles with a longer history of struggling to address mental health issues.

A recent ProPublica investigation looked at every VA inspector general report over the past four years, “including 162 regular surveys of facilities and 151 investigations triggered by a complaint or call to the office on a wide variety of alleged health care problems.” That review found a healthcare system, the nation’s largest, plagued by systemic problems.

“Issues with mental health care surfaced in half of the routine inspections,” the nonprofit newsroom reported. “Employees botched screenings meant to assess veterans’ risk of suicide or violence; sometimes they didn’t perform the screenings at all. They missed mandatory mental health training programs and failed to follow up with patients as required by VA protocol.

“One in four of the reports stemming from calls or complaints detailed similar breakdowns. In the most extreme cases, facilities lost track of veterans or failed to prevent suicides under their own roofs.”

VA Inspector General Michael Missal’s only response to ProPublica’s reporting was a written statement: “Our reports have repeatedly illustrated that it is critical that [Veterans Health Administration] leaders remain vigilant to problems, ensure care is coordinated, and take swift, responsive actions that address root causes and promote accountability.”

Finally, ProPublica also reported that the VA inspector general published a survey last fall that showed “more than three-quarters of the VA’s 139 networks of hospitals and associated clinics had reported ‘severe’ shortages of psychiatrists, psychologists, or both.” This comes at a time when more veterans are clamoring for better access to mental health services.

Further Reading:

Mortality Within 1 Year After Suicide Attempt