Because this piece does not have an abstract, we have provided for your benefit the first 3 sentences of the full text.

Have you ever wondered whether you could facilitate better collaboration with a patient who appears to reject your help during an acute medical event? Have you ever had trouble engaging a patient so that he or she would consider alternatives to decisions that are not in his or her best interest or are even against medical advice? If you have, then the following case vignettes and discussion could prove useful.

Engaging the Resistant Patient in the Implementation of Interventions

LESSONS LEARNED AT THE INTERFACE OF MEDICINE AND PSYCHIATRY

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Dr Raffi is a perinatal and reproductive psychiatrist at the Massachusetts General Hospital’s Center for Women’s Mental Health, and the HOPE Clinic for perinatal women with substance use disorders. He is an instructor in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. Dr Traeger is a clinical psychologist in the Behavioral Medicine Program and the Center for Psychiatric Oncology, a member of the Cancer Outcomes Research (CORe) Program, and associate director of the Qualitative Research Unit in the Division of Clinical Research at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. She is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston Massachusetts. Dr Stern is chief emeritus of the Avery D. Weisman Psychiatry Consultation Service, director of the Thomas P. Hackett Center for Scholarship in Psychosomatic Medicine, director of the Office of Clinical Careers at Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Ned H. Cassem professor of psychiatry in the field of psychosomatic medicine/consultation at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. Dr Stern is the editor in chief of Psychosomatics.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2018;20(3):17f02136

To cite: Raffi ER, Traeger LN, Stern TA. Engaging the resistant patient in the implementation of interventions. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(3):17f02136.

To share: https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.17f02136

© Copyright 2018 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

*Corresponding author: Theodore A. Stern, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Fruit St, WRN 605, Boston, MA 02114 ([email protected]).

aCenter for Women’s Mental Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

bDepartment of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

cQualitative Research Unit, Division of Clinical Research, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

dMassachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Have you ever wondered whether you could facilitate better collaboration with a patient who appears to reject your help during an acute medical event? Have you ever had trouble engaging a patient so that he or she would consider alternatives to decisions that are not in his or her best interest or are even against medical advice? If you have, then the following case vignettes and discussion could prove useful.

CASE 1

A Man With Hypertensive Urgency

Mr A, a 52-year-old veteran with a history of hypertension and protracted paranoid psychosis, was noted by a nurse at his residential facility to have a markedly elevated blood pressure (210/110 mm Hg). When the physician on call recommended use of an oral antihypertensive agent, Mr A refused. Although the physician concluded that medication refusal was Mr A’s right, the nurse sought psychiatric consultation to improve adherence with treatment recommendations.

The psychiatrist asked Mr A if he knew his typical baseline blood pressure readings. Mr A indicated that they were usually 160/90 mm Hg. The psychiatrist then asked the nurse to measure Mr A’s blood pressure with an electronic reader so that the patient could see the result. Mr A noted that the blood pressure reading was 210/110 mm Hg. The psychiatrist asked if this reading was higher than his baseline blood pressure, and Mr A said "yes." The psychiatrist then recommended an oral antihypertensive agent to decrease his blood pressure. Mr A explained that he refused to take the medication because he did not believe in oral medication. The psychiatrist proposed that Mr A try an antihypertensive pill but insisted that the nurse show him his blood pressure on the digital reader 45 minutes later. Mr A agreed that if he saw a drop in his blood pressure he would believe that the medication had worked. However, if the pill did not work, Mr A could continue to abstain from taking antihypertensive pills. Mr A agreed with the plan and took the antihypertensive agent. Mr A’s blood pressure decreased within 30 minutes.

CASE 2

A Woman With Acute Stroke

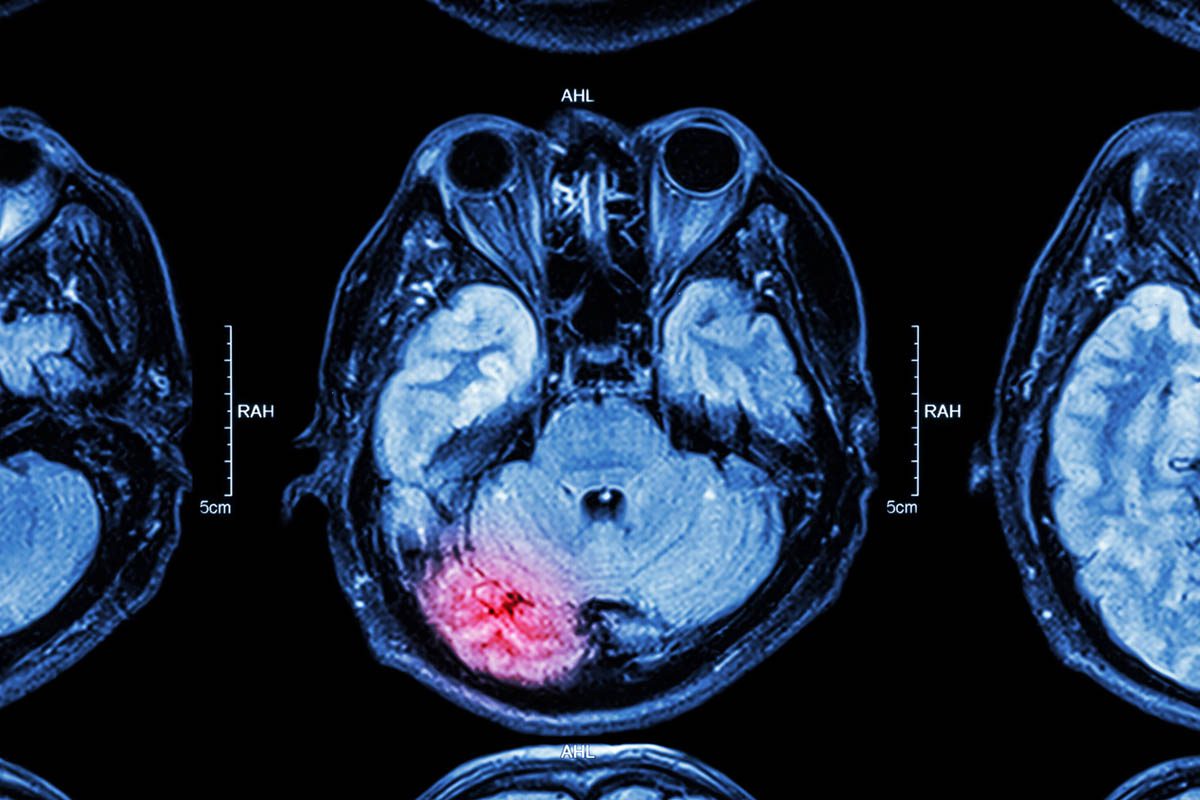

Ms B, a 56-year-old woman with a history of diabetes and myocardial infarction, presented to the hospital emergency department with left-sided upper extremity motor weakness, drooping of the mouth, and slurred speech for the past hour. Imaging confirmed a right-sided cerebrovascular accident. The neurology department was consulted, and they recommended that Ms B be admitted to the hospital for monitoring and treatment. Ms B explained that she was aware that she had experienced a stroke but wanted to decline admission. As a nurse, she understood how to manage an acute stroke, but she wanted to be discharged home. When the physician asked why she wanted to leave the hospital, Ms B explained that her granddaughter was performing in a school play, and she had promised that she would be there. Ms B said, "You will just be monitoring me and my blood pressure anyway. I would rather be at the play tonight. I will think about coming back tomorrow or the next day. I will sign whatever you want me to sign in order to leave." When asked about risks of discharge, Ms B said, "I know there is a risk of worsening motor and sensory loss and even death. I don’ t want to continue this conversation further. I would like to be discharged." The psychiatry department was called for a capacity evaluation, which further infuriated Ms B.

- Individuals do not often change, or change their minds, for other people; moreover, a resistant patient is unlikely to change his or her mind because he or she is told to change.

- When discussing change, it is important to view patients as collaborators; patients’ values and beliefs should be considered as an essential part of clinical negotiations.

- Collaboration between physicians and patients can be facilitated by addressing the control dynamics between them through brief behavioral interventions.

- Treatment recommendations are more likely to be followed when physicians understand the patient’s perspective, facilitate the patient’s insight into his or her condition, increase the patient participation in decision-making, and employ alliance-building techniques.

After evaluating Ms B, the psychiatrist realized that she had the capacity to refuse admission.

Psychiatrist: "I understand that you know the risks of leaving the hospital and are choosing to decline admission. On a scale of 1 to 10, how safe do you think it is to leave the hospital?"

Ms B: "8."

Psychiatrist: "Why 8 and not 10?"

Ms B: "I give it a 20% chance that the hemorrhage might get worse."

Psychiatrist: "What difference would it make if you were in the hospital if that occurred?"

Ms B: "They would control my blood pressure and might even perform surgery. Coiling is an option if you have an interventionist."

Psychiatrist: "I understand that you are accepting the risk of hemorrhage, while trying to keep your promise to your granddaughter. If your condition worsens after you have left the hospital without an intervention, what might your granddaughter think now or when she grows up about this entire event?"

Ms B: "She will know that I cared enough to be with her and that I kept my promise."

Psychiatrist: "Yes’ ¦" (nods waiting for more).

Ms B: "I suppose she might also feel some guilt."

Psychiatrist: "Would that guilt be justified?"

Ms B: "No. It would have been my decision. She shouldn’ t feel guilty. But people have a way of personalizing these events."

Psychiatrist: "I am going to ask you the following question because I am not sure of the significance of this play to your relationship with your granddaughter. What is so important about attending the school play?"

Ms B: "I have been teaching her about the importance of keeping her promises’ ¦and this was my promise to keep."

Psychiatrist: "Would it be acceptable to you if someone couldn’ t keep their promise due to a life-threatening event?"

Ms B: "I suppose there are exceptions to every rule, and the exceptions are also important to teach."

Psychiatrist: "Are there any other more important events in your future that would make you not want to accept a 20% risk of a worsening stroke or death?"

Ms B: "I would definitely want to be at my granddaughter’s graduation, 100%, and perhaps her wedding if I live that long."

DISCUSSION

What Factors Affect Engaging the Resistant Patient in Care?

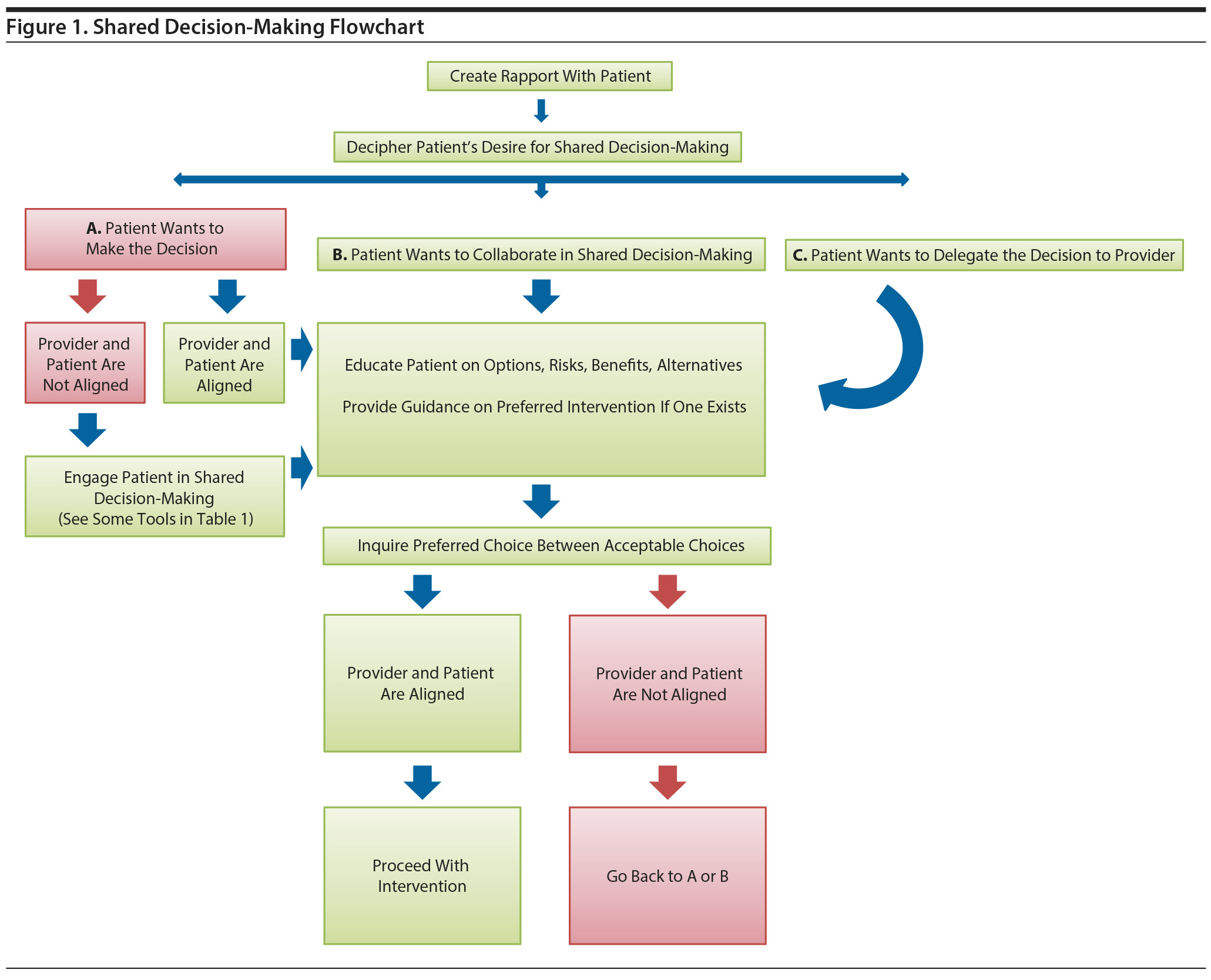

Negotiations regarding treatment, especially in the midst of a crisis, can be more than challenging. Nonetheless, addressing patient nonadherence with real-time behavioral interventions can enhance patient safety and mitigate morbidity and mortality (Figure 1).

Conflict among patients and health care providers often arises when initiating medical interventions, such as starting a medication. Roughly 1 in 4 patients with psychosis fails to adhere to initial treatment recommendations.1 In those with personality disorders, for example, the window of opportunity to agree on an intervention is typically small as a consequence of impulsivity, intense affects, and ineffective coping skills. These characteristics escalate emotions and contribute to worse health outcomes. Nonadherence is common in all branches of clinical medicine with rates ranging between 25% and 75%.2

Providers should be aware of factors known to interfere with adherence (including patient factors [eg, cognitive impairment, poor insight, stigma], the setting [eg, inpatient, outpatient], provider factors [eg, approaches to patient care], and systems factors [eg, health care fragmentation]).2-5 Patients often feel that they have too much or a lack of "perceived control" over their situation.

Knowledge of the patient’s preferences and values is crucial to developing and employing effective approaches. Patients are also less likely to participate in their care if they have limited insight into their condition, are not ready to change their behavior, or believe that the recommended intervention is unnecessary or ineffective.3 For some patients, the patient’s participation in planning the intervention facilitates the intervention.2 In the case of Mr A, reasoning might have been insufficient given his persistent paranoia. Such individuals (with disorganization, hostility, and paranoia) are not as likely to adhere to medication use.5 Insight into one’s condition also influences medication adherence, as poor insight has been consistently correlated with lack of compliance or adherence.5-9 The belief that the medication will provide an immediate and subjective sense of improvement increases the chances of adherence.3,4

What Led to Increased Collaboration Between the Psychiatrist and Mr A?

Mr A might not have understood the severity of his hypertension or the associated risks. By including him in the reasoning process and engaging him in the dialog, he was able to follow a logical path. Namely, he could agree that the numbers that appeared on the blood pressure monitor were higher than the numbers he knew to be his norm; moreover, he could help to decrease his blood pressure.

Although he was quite paranoid, he was still able to reason. Thus, by being mindful of Mr A’s world view and lack of insight into the consequences of his hypertension, the psychiatrist was able to create a tailored approach to treatment.

The psychiatrist utilized cognitive reframing and helped Mr A to exercise his need for control on how he takes his medication—not whether he takes his medication. Together they achieved adherence by identifying Mr A’s beliefs that oral medications do not work, acknowledging this belief in a nonjudgmental fashion, and then helping Mr A collect reasonable evidence to challenge his own belief. This nonjudgmental approach allowed the psychiatrist to effectively align the treatment recommendations with Mr A’s thoughts and behaviors.

Which Factors Led Ms B to Change Her Mind?

As shown in the case of Mr A, individuals do not often change, or change their minds, for other people. They change when their own logic dictates change. A resistant patient is unlikely to change his or her mind because they are told to change. Ms B had the capacity to make decisions even if those choices were against medical advice. The technique used by the psychiatrist to help Ms B understand the gravity of her decision and help her decide to change her own mind is called motivational interviewing.10 The psychiatrist used motivational interviewing to help Ms B generate her own intrinsic motivation to be admitted to the hospital for monitoring and treatment. Motivational interviewing is a counseling style that can help set the stage for therapy with individuals who are poorly motivated to reduce unhealthy behaviors or increase health-promoting ones.

Importantly, serious illness or acute illness can lead patients to feel a decreased sense of control or self-efficacy. Thus, a patient’s viewpoint must be validated. For example, Ms B saw value in being able to attend her granddaughter’s play. A physician who sounds dismissive of that view will lose an opportunity to connect with her and facilitate "change talk." Change talk is the type of language patients tend to use when they think about changing their mind.

To move toward change talk, providers should acknowledge the patient’s mindset. Then, "Socratic questioning" (also used in cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) can guide critical thinking about the issue. Using the 80%-20% scale, the psychiatrist showed Ms B that she was taking a 20% chance on many things that are important to her that she had not previously considered. Once change talk is detected, it is encouraged by the provider’s further questioning so that the patient explores the benefits of change and then desires that this change come from within. Ms B put a lot of emphasis on teaching her granddaughter about keeping promises, but she had not explored her teachings about the importance of "exceptions to rules." She also had not considered what she was risking with regard to the future.

The techniques developed for ongoing therapeutic modalities (Table 1) can be used in acute care settings as well. Every interaction is a chance for an intervention when it comes to helping patients make healthier decisions.

How Can the Alliance Between the Patient and Provider Be Bolstered?

In general, when discussing change it is important to view patients as collaborators; patients’ values and beliefs should be considered as an essential part of clinical negotiations.12,13 Physicians must consider ways in which physician-patient power dynamics influence a patient’s perceived "control disadvantage." Awareness and adjustment of this dynamic can facilitate alliance building that will improve adherence. The association between the therapeutic alliance and medication adherence (independent of the patient’s severity of psychopathology, type/dosage of medication, or inpatient/outpatient status) has been studied.14

To develop a greater sense of autonomy, patients often need to feel that they have as much or as little control over their treatment as they want. It is the physician’s responsibility to gauge how much control a patient perceives he or she has over a situation and whether more or less control is desired. This notion of maintaining a "control equilibrium" involves open and nonjudgmental communication. For some patients, feeling that one is empowered by shared decision-making can enhance adherence with treatment recommendations.

On occasion, patients feel that they are given too much control. For example, a low-functioning patient might be told about the risks, benefits, and side effects of 2 antipsychotic medications. The physician might then ask the patient to choose 1 of 2 drugs. The patient, however, might seek the physician’s recommendation, thereby shifting control to the provider. Such a request might be answered by a defensive-medicine response of "it is your choice." In this scenario, the doctor would be refusing to take more control when the patient asks for this shift. The physician, however, might choose to ask additional questions to help make a decision that is consistent with the patient’s goals, preferences, or values. If the patient walks away after having made a less-than-confident decision, adherence might not be as likely.

While the patients presented here have known psychiatric conditions (Mr A) or acute illnesses (Ms B), lessons learned from these challenging cases can be applied to the care of almost every patient.

CONCLUSION

Treatment recommendations are more likely to be followed when physicians understand the patient’s perspective, facilitate the patient’s insight into his or her condition, increase patient participation in decision-making, and employ alliance building. The current cases illustrate the use of biofeedback (Mr A) and motivational interviewing (Ms B) to facilitate physician-patient collaboration for enhanced treatment outcomes. Collaboration between physicians and patients who may initially appear to be rejecting medical advice can be facilitated by addressing the control dynamics between patients and providers through brief behavioral interventions.

Submitted: March 14, 2017; accepted April 12, 2018.

Published online: May 31, 2018.

Potential conflicts of interest: Dr Stern is an employee of the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry and has received royalties from Elsevier and the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy. Drs Raffi and Traeger report no conflicts of interest related to the subject of this article.

Funding/support: None.

REFERENCES

1. Nosé M, Barbui C, Tansella M. How often do patients with psychosis fail to adhere to treatment programs? a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1149-1160. PubMed CrossRef

2. Eisenthal S, Emery R, Lazare A, et al. ‘ Adherence’ and the negotiated approach to patienthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36(4):393-398. PubMed CrossRef

3. Traeger LN, Herman JB, Stern TA. Patient adherence. In: Stern TA, Herman JB, Rubin D, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Update and Board Preparation. 4th ed. Boston, MA: MGH Psychiatry Academy; 2018.

4. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(4):637-651. PubMed CrossRef

5. Marder SR, Mebane A, Chien CP, et al. A comparison of patients who refuse and consent to neuroleptic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(4):470-472. PubMed CrossRef

6. Tham XC, Xie H, Chng CML, et al. Factors affecting medication adherence among adults with schizophrenia: a literature review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2016;30(6):797-809. PubMed CrossRef

7. Sendt KV, Tracy DK, Bhattacharyya S. A systematic review of factors influencing adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225(1-2):14-30. PubMed CrossRef

8. Lin IF, Spiga R, Fortsch W. Insight and adherence to medication in chronic schizophrenics. J Clin Psychiatry. 1979;40(10):430-432. PubMed

9. McEvoy JP, Apperson LJ, Appelbaum PS, et al. Insight in schizophrenia: its relationship to acute psychopathology. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177(1):43-47. PubMed CrossRef

10. Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1995;23(4):325-334. CrossRef

11. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

12. Lazare A, Cohen F, Jacobson AM, et al. The walk-in patient as a ‘ customer’ : a key dimension in evaluation and treatment. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1972;42(5):872-883. PubMed CrossRef

13. Lazare A, Eisenthal S, Wasserman L. The customer approach to patienthood: attending to patient requests in a walk-in clinic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32(5):553-558. PubMed CrossRef

14. Frank AF, Gunderson JG. The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of schizophrenia: relationship to course and outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(3):228-236. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy free PDF downloads as part of your membership!

Save

Cite

Advertisement

GAM ID: sidebar-top