Abstract

Objective: To examine the complexities of psychotropic medication prescription in home-based palliative care for oncology patients.

Methods: A retrospective analysis of 125 medical records of patients receiving palliative home care for cancer was conducted at a tertiary hospital, with a specific focus on the prescription patterns of psychotropic medications. The data were collected in September 2023.

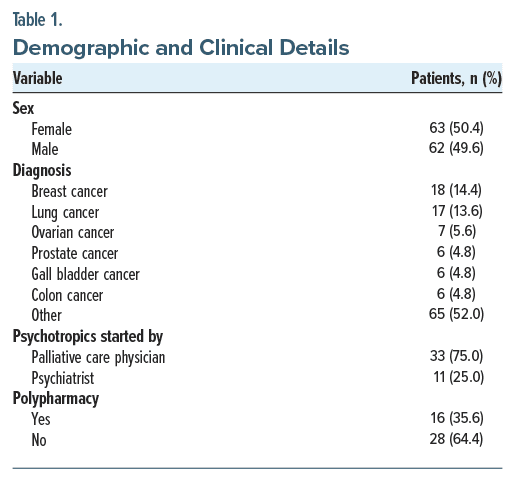

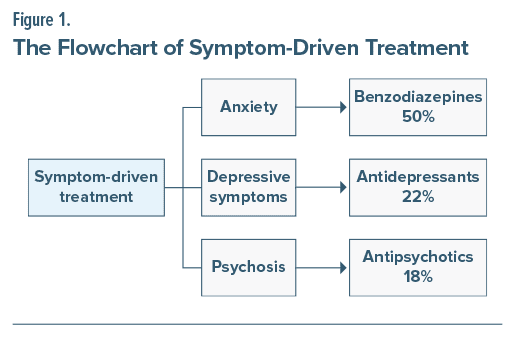

Results: Among 125 cases, the mean age was 64.4 ± 14.9 years, with 50.4% females. Breast cancer (14.4%) and lung cancer (13.6%) were the most common diagnoses. Psychotropic medication was administered to 35.2% of patients. Treatment was initiated by palliative care doctors in 75% of cases, while psychiatrists handled 25%. Medication selection was predominantly symptom driven (63%), with anxiety prompting benzodiazepine prescriptions in 50% of cases, depression resulting in antidepressant use in 22%, and psychosis leading to antipsychotic treatment in 18%. Specific diagnoses were the target in only 36% of prescriptions, with delirium (27%) being the most prevalent, followed by depression and bipolar disorder. Benzodiazepines were the most commonly prescribed class of medications (56.8%), with clonazepam being the most prevalent (40.9%), followed by alprazolam and lorazepam (15.9%). Atypical antipsychotics made up 43.1% of prescriptions, with quetiapine being the most frequently prescribed (34%), along with olanzapine and risperidone (11%). Antidepressants accounted for 31.8% of prescriptions, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors at 18% and mirtazapine and amitriptyline at 6% each. Haloperidol, a typical antipsychotic, was prescribed in 13.6% of cases. Polypharmacy was observed in 35.6% of patients.

Conclusion: In palliative home care, psychotropic medications are frequently prescribed by palliative doctors primarily for symptom management, with limited psychiatric consultations and challenges in accessing psychological evaluations. Collaborative efforts among regional or institutional medical bodies, including psychiatrists, psychologists, palliative doctors, and social workers, are needed to establish ethical guidelines for appropriate and effective psychotropic prescription.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2024;26(2):23m03668

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Cancer diagnosis impacts the psychological well being of the patient, stemming from the fear of imminent mortality, the burden of aggressive treatments, shifting social roles, and diminished autonomy. It has been reported that there is a prevalence of various diagnosed psychiatric conditions in cancer patients on palliative treatment, including depression or adjustment disorder in around 25% of patients, anxiety disorders in around 10% of patients, and all types of mood disorders in 30% of patients.1 There is a need to effectively address these psychological issues, as it can significantly improve the overall quality of life for patients and their families.2

However, a substantial portion of these patients receive palliative care in a home-based setting, which, unfortunately, results in limited access to specialized psychiatric care. The accessibility is limited because of many factors including economic constraints, commuting challenges for bed-bound patients, and limited number of psychiatrists and psychologists available for home visits.3 Also, most patients cannot adhere to regular psychotherapy for their psychological symptoms. Therefore, psychotropic medications emerge as a crucial and practical treatment option for addressing psychiatric symptoms in palliative oncology patients. Also in this unique context, the responsibility for managing these psychiatric issues largely falls upon palliative care physicians.

While the incidence of psychiatric disorders is well documented, there is a paucity of research examining the practices of prescribing psychotropic medications in this context.4 This gap in knowledge limits the care delivered to this vulnerable patient population. This study seeks to bridge this knowledge gap by examining the complexities of psychotropic medication prescription in home-based palliative care for oncology patients to ultimately contribute to the enhancement of patient centered care in the face of terminal illness.

METHODS

In this retrospective study, we reviewed case sheets of 125 cancer patients registered under palliative home care in a tertiary-level private hospital in Kozhikode, Kerala, India. The case sheets of the most recent 125 cancer patients registered with the palliative home care service were reviewed individually in a systematic manner. Basic data included age, gender, type of cancer, and whether the patient was alive or had died at the time of the study. Further details regarding the use of psychotropics, indication for use, class of psychotropics, and whether polypharmacy was present or not were surveyed from the case sheets. The prevalence of psychotropic medication use was estimated as the proportion of cancer patients with any psychotropic medication prescribed. The data were collected in September 2023.

Indication for psychotropic prescription was noted from the doctor’s note made by the doctor at each visit before adding the medication in the drug chart. Patients who were prescribed psychotropic class medication for nonpsychiatric indications were omitted from the study. Indication for use was classified under broad headings: whether the prescription was symptom-driven or whether a diagnosis was made prior to prescription. Symptom-driven treatment was classified under depressive symptoms, psychotic symptoms, and symptoms related to anxiety. Specific diagnoses encountered during the study were delirium, depression, and bipolar disorder.

Additionally, the psychotropics received were classified broadly into antidepressants, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines. The prevalence of specific psychotropic medication use was calculated as the percentage of cancer patients with a specific medication prescribed for all cancer patients with psychotropic medication use. Each drug was also listed under specific subtypes (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs] and typical and atypical antipsychotics) under the specific psychotropic class.

RESULTS

Among 125 cases, the mean age was 64.4 ± 14.9 years, with 50.4% females. Breast cancer (14.4%) and lung cancer (13.6%) were the most common diagnoses. Psychotropic medication was administered to 35.2% of patients. Palliative doctors initiated treatment in 75% of cases, while psychiatrists handled 25%. Demographic and clinical details are summarized in Table 1.

Medication selection was predominantly symptom driven (63%), with anxiety prompting benzodiazepine prescriptions in 50% of cases, depression resulting in antidepressant use in 22%, and psychosis leading to antipsychotic treatment in 18%. Symptom-driven treatment is summarized in Figure 1. Specific diagnoses were the target in only 36% of prescriptions, with delirium (27%) being the most prevalent, followed by depression and bipolar disorder.

Benzodiazepines were the most commonly prescribed class of medications (56.8%), with clonazepam being the most prevalent (40.9%), followed by alprazolam and lorazepam (15.9%). Atypical antipsychotics made up 43.1% of prescriptions, with quetiapine being the most frequently prescribed (34%), along with olanzapine and risperidone (11%). Antidepressants accounted for 31.8% of prescriptions, including SSRIs at 18% and mirtazapine and amitriptyline at 6% each. Haloperidol, a typical antipsychotic, was prescribed in 13.6% of cases. Polypharmacy was observed in 35.6% of patients.

DISCUSSION

Most patients with advanced cancer develop multiple devastating physical and psychosocial symptoms, usually for weeks or months before death.5 It is clear from our study and the existing literature that psychotropics are frequently employed to alleviate these symptoms, particularly the psychological ones, in current palliative practices.6 Our study revealed a psychotropic usage rate of 35.2%, while a similar cross-sectional study conducted in China during 2015–2017 reported an overall prevalence of 18.5%.7

Our study showed that only a quarter of psychotropic prescriptions were initiated by psychiatrists, and most of the prescriptions were symptom-driven. This finding indicates that many patients who needed detailed psychosocial evaluation for their symptoms went unassessed and undiagnosed due to the impracticality of psychiatric or psychological consultations on several occasions. Our study was conducted at a charitable palliative organization, and a significant portion of the patients received services for free or at minimal cost. This was because many patients’ families belonged to lower economic strata, leading to evident economic constraints in accessing comprehensive psychiatric care. Another significant challenge is the limited time available to palliative doctors during home visits. These doctors must also address other concerns such as pain management and various supportive care needs, leaving them with restricted time to adequately address the psychological needs of the patient.

Another study that assessed the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in hospital-based cancer patients in the same region as ours, Kerala, India, during 20168 reported that 41.7% of patients had psychiatric disorders, with depression and anxiety disorders accounting for 33.5% of cases and delirium observed in 6.5% of patients. Our study yielded similar results, with symptoms related to anxiety and depression being more common and delirium emerging as the most frequent diagnosis.

Benzodiazepines are the most commonly prescribed psychotropic drugs for cancer patients worldwide. They are often administered to assist patients in managing sleep-related issues.9 The studies conducted in China and the Netherlands7,10 indicate that benzodiazepines were the most frequently prescribed psychotropics. It is worth noting that our study also yielded similar results, with clonazepam being the most commonly prescribed drug (40.9%). This finding clearly demonstrates that even in diverse economies and health care systems, benzodiazepines are commonly used by cancer patients. However, there is still a gap in the literature regarding the guidelines and settings for prescribing these drugs.

Quetiapine emerged as the second most frequently prescribed psychotropic drug, primarily for the treatment of delirium. In our study, SSRIs (18%) constituted the majority of prescribed antidepressants, which differs from the study7 from China, in which a common prescription involved a combination of atypical antipsychotics and tricyclic antidepressants.

Interestingly, various psychotropics have been discovered to be beneficial for the adjuvant treatment of cancer-related symptoms, including pain, hot flashes, pruritus, nausea and vomiting, fatigue, and cognitive impairment. This underscores the importance of psychopharmacology as a tool for enhancing the quality of life for cancer patients.11 However, it is important to note that this study did not assess the effectiveness of psychotropic drugs for managing these symptoms in palliative care, and, in general, psychotropics were not used for these symptoms in the institution of our study.

This study highlights that in many cases, palliative care doctors often have no choice but to directly prescribe psychotropics for home-based palliative cancer patients. Nevertheless, the lack of clear guidelines, even at the institutional levels, significantly restricts the potential for a more ethical and suitable use of psychotropics in cancer patients.

It is also evident that providers face discomfort while prescribing psychotropics12 due to a variety of reasons; hence, it is important to provide health care professionals, especially those in oncology and palliative care, with focused mental health education and ongoing training to ensure they can address the psychological well-being of their patients effectively. A clinical pathway for prescribing psychotropic medications, along with resources for long-term mental health care, could indeed help improve patient care and prescribing comfort.

CONCLUSION

In palliative home care, psychotropic medications are frequently prescribed by palliative care doctors primarily for symptom management, with limited psychiatric consultations and challenges in accessing psychological evaluations. Collaborative efforts among regional or institutional medical bodies, including psychiatrists, psychologists, palliative doctors, and social workers, are needed to establish ethical guidelines for appropriate and effective psychotropic prescription.

Article Information

Published Online: May 2, 2024. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.23m03668

© 2024 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: November 2, 2023; accepted December 28, 2023.

To Cite: Mohamed F, Uvais NA, Moideen S, et al. Psychotropic medication prescriptions for home-based palliative care oncology patients. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2024;26(2):23m03668.

Author Affiliations: Department of General Medicine, IQRAA International Hospital, Kozhikode, Kerala, India (Mohamed, Moideen, Saif); Department of Psychiatry, IQRAA International Hospital, Kozhikode, Kerala, India (Uvais); Department of Palliative Medicine, IQRAA International Hospital, Kozhikode, Kerala, India (Rahman CP).

Corresponding Author: N. A. Uvais, MBBS, DPM, Department of Psychiatry, IQRAA International Hospital and Research Centre, Malaparamba 673009, Kozhikode, Kerala, India ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Previous Presentation: The data included in this study were presented as an oral presentation at MIND CAN 2023 “The Art and Science of Closing the Care Gap in Cancer” One Day National Conference on Psycho-Oncology; October 14, 2023.

Clinical Points

- Psychotropic medications were frequently prescribed in palliative home care for cancer patients, predominantly by palliative care doctors and based on symptom management, with limited psychiatric consultations.

- Prescription patterns focused on managing symptoms such as anxiety, delirium, and depression, but specific psychiatric diagnoses were targeted in a minority of cases.

- Polypharmacy, observed in over a third of patients, highlights concerns about potential drug interactions and adverse effects in terminally ill cancer patients receiving psychotropic medications in palliative care.

References (12)

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160–174. PubMed CrossRef

- Kozlov E, Niknejad B, Reid MC. Palliative care gaps in providing psychological treatment: a review of the current state of research in multidisciplinary palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(3):505–510. PubMed CrossRef

- O’Malley K, Blakley L, Ramos K, et al. Mental healthcare and palliative care: barriers. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021;11(2):138–144.

- Breitbart W, Bruera E, Chochinov H, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes and psychological symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10(2):131–141. PubMed CrossRef

- Azhar A, Hui D. Management of physical symptoms in patients with advanced cancer during the last weeks and days of life. Cancer Res Treat. 2022;54(3):661–670. PubMed CrossRef

- Fairman N, Irwin SA. Palliative care psychiatry: update on an emerging dimension of psychiatric practice. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(7):374. PubMed CrossRef

- Bai L, Xu Z, Huang C, et al. Psychotropic medication utilisation in adult cancer patients in China: a cross-sectional study based on national health insurance database. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2020;5:100060. PubMed CrossRef

- Gopalan MR, Karunakaran V, Prabhakaran A, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among cancer patients – hospital-based, cross-sectional survey. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58(3):275–280. PubMed CrossRef

- Goldberg RJ, Cullen LO. Use of psychotropics in cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 1986;27(10):687–692, 697–698, 700. PubMed CrossRef

- Ng CG, Boks MP, Smeets HM, et al. Prescription patterns for psychotropic drugs in cancer patients; a large population study in the Netherlands. Psychooncology. 2013;22(4):762–767. PubMed CrossRef

- Caruso R, Grassi L, Nanni MG, et al. Psychopharmacology in psycho-oncology. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(9):393. PubMed CrossRef

- Biringen EK, Cox-Martin E, Niemiec S, et al. Psychotropic medications in oncology. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(11):6801–6806. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy free PDF downloads as part of your membership!

Save

Cite

Advertisement

GAM ID: sidebar-top