Because this piece does not have an abstract, we have provided for your benefit the first 3 sentences of the full text.

Have you ever wondered whether physicians have the right to restrict patients’ behavior when they are voluntary inpatients? As a health care provider, have you been afraid to be flexible when enforcing rules imposed upon patients for fear of liability if a bad outcome were to arise? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

Rules Imposed by Providers on Medical and Surgical Inpatients With Substance Use Disorders:

Arbitrary or Appropriate?

LESSONS LEARNED AT THE INTERFACE OF MEDICINE AND PSYCHIATRY

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2018;20(6):18f02341

To cite: Frank RC, Islam YFK, Johnson SW, et al. Rules imposed by providers on medical and surgical inpatients with substance use disorders: arbitrary or appropriate? Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(6):18f02341.

To share: https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.18f02341

© Copyright 2018 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

aDepartment of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

bHarvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

cDepartment of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

‘ ¡Authors contributed equally to this article.

*Corresponding author: Theodore A. Stern, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Fruit St WRN 605, Boston, MA 02114 ([email protected]).

Have you ever wondered whether physicians have the right to restrict patients’ behavior when they are voluntary inpatients? As a health care provider, have you been afraid to be flexible when enforcing rules imposed upon patients for fear of liability if a bad outcome were to arise? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

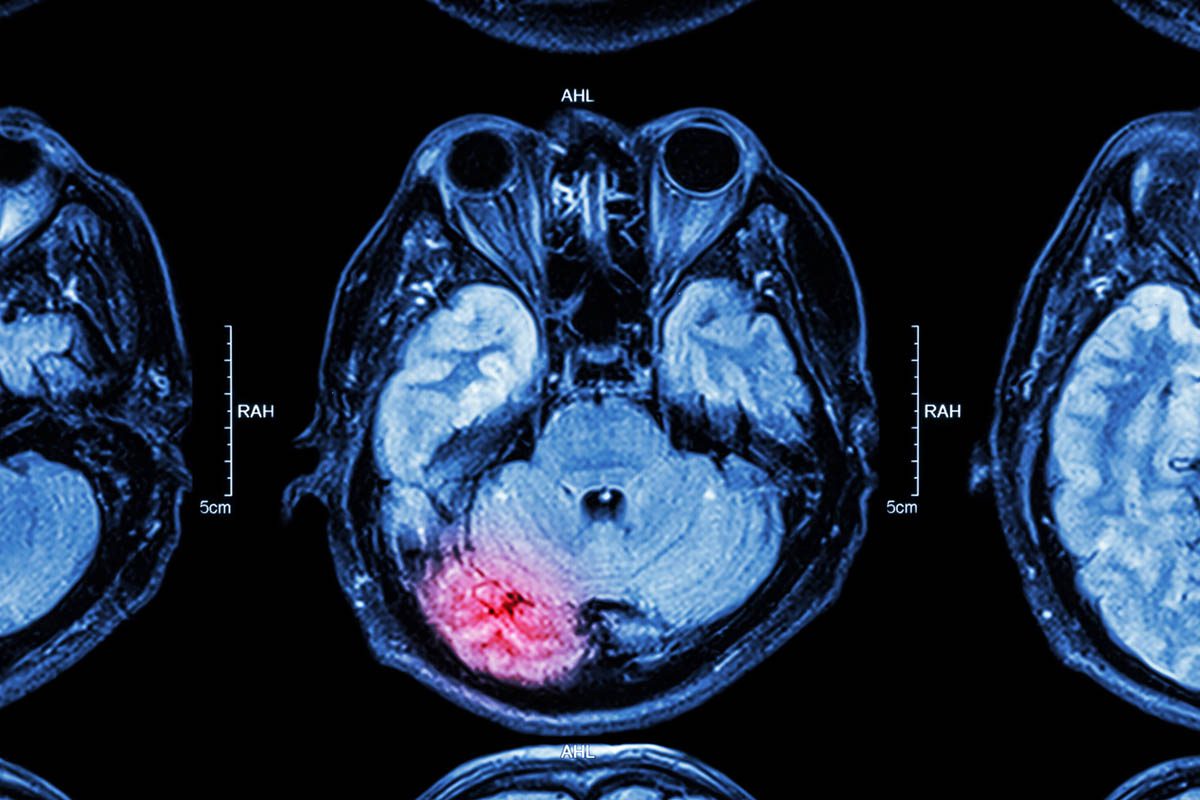

Ms A, a 28-year-old woman with a history of intravenous (IV) heroin use, presented with a fever of 3 months’ duration; her medical workup indicated endocarditis. A peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) was placed for several weeks of IV antibiotic administration and blood draws, as her veins were difficult to access given her history of IV drug abuse. Soon after hospital admission, she requested permission to go outside and smoke. The nurses and resident physicians caring for Ms A were concerned that she might inject illicit drugs into her PICC if she were to go outside alone, so they denied the request. Initially, Ms A accepted this decision; however, after her boyfriend arrived and told her that he had seen other patients smoking outside, she became upset. Ms A felt that the medical team was discriminating against her because of her substance use disorder. There was disagreement among the health care team about what the most appropriate response should entail. Some providers were willing to let her travel off the floor to smoke if she was accompanied by a physician or a nurse. Others felt that the team should not set a precedent (ie, letting Ms A go outside with one of them) because it would engender stress and anger when the physicians or nurses were too busy to chaperone her.

discussion

Which Patients Require Rules During Their Inpatient Stay?

Rules and limitations on behaviors are often necessary for medical and surgical inpatients whose behavior, when unsupervised, increases their risk of an adverse outcome. While patients’ histories vary (eg, congestive heart failure, end-stage renal disease, delirium, dementia, substance use disorders, eating disorders, repeated self-injurious behaviors, and other psychiatric comorbidities), poor adherence to diet, ambulation without adequate monitoring or support, affective dysregulation, and cognitive impairment can be problematic and require that these patients be placed under certain restrictions for their health and safety.

- Rules and limitations on behaviors are often necessary for medical and surgical inpatients whose behavior, when unsupervised, increases their risk of an adverse event.

- Providers should approach the topic of setting limits with compassion, explaining the rationale behind provider-enforced rules.

- Providers are often concerned about the potential for liability when one of their patients who abuses intravenous drugs uses them in the hospital.

For patients with decompensated congestive heart failure or end-stage renal disease, clinician-determined limitations often focus on fluid restrictions and adherence with electrolyte-specific diets. However, the more challenging practice, albeit less well defined, centers on setting limits for hospitalized patients with histories of substance use disorders, eating disorders, self-injurious behaviors, and psychiatric illness.

Specific limitations established by clinicians, hospitals, and patient-specific situations vary, but they often involve limiting use of personal electronic devices (such as cell phones) and access to personal supplies of medication and sharp objects (eg, metal silverware to limit self-injurious behavior).2,3 Moreover, patients at risk of tampering with their IV lines, binging or purging food, or cutting themselves often need direct line-of-sight supervision.4

Why Are Rules Necessary for Certain Patients?

Not all patients have limitations placed on their behavior when they are admitted to the hospital. Inpatients most likely to have rules applied and enforced are those with substance use disorders and psychiatric conditions, as practitioners are concerned that unmodulated behaviors may place the patient or others at risk. Health care professionals also often view these patients in a negative light and treat them differently.5

Other patients who need to be monitored continuously may face behavioral restrictions (eg, forbidding them to leave the inpatient floor to prevent unsafe and unmonitored events). For instance, on an epilepsy-monitoring unit, smokers had 3.7 times more unwitnessed seizures than did their nonsmoking counterparts, resulting in a length of stay that was, on average, 1.5 days longer than their nonsmoking colleagues who remained on the inpatient floor.6 Similar concerns exist for patients who are on suicide precautions, which result in restrictions preventing them from leaving the inpatient floor or from using the bathroom without someone directly visualizing them.

Equally concerning are patients with substance use disorders who use their IV lines for injection of illicit drugs. Unfortunately, data regarding rates of infection and death due to inpatients accessing their own IV lines are lacking; however, anecdotal reports suggest that staff believe that patients are accessing their lines, potentially leading to infection, more often than physicians anticipate. For example, one service in an academic hospital had 16 blood-borne infections in a single year due to injection drug users accessing their lines.7 To prevent such infections, the hospital’s security staff started to perform room searches for patients suspected of misusing their IVs, and their visitors were limited. These regulations on behavior were intended to prevent use of illicit substances while hospital-placed IV lines were accessible.7

In addition to the application of rules, there are other pharmacologic therapies that may decrease craving for opiates or nicotine (eg, with tobacco use) and can be useful when utilized in concert with behavioral plans. Strong evidence exists regarding the use of methadone, suboxone, and naltrexone to decrease cravings and treat opiate use disorder,8 with data to support initiation of opiate antagonists even during the initial presentation to the emergency department.9 For opiate users who are hospitalized frequently for medical issues (including infections), hospitalization may be the opportune time to engage patients in treatment with medications such as buprenorphine.10 Furthermore, nicotine replacement therapy and adjunctive pharmacologic therapies, such as varenicline and bupropion, may also decrease urges to go outside to smoke.11 While these medications may not completely eliminate the urge to smoke or use opiates, decreasing the urge to go outside may decrease disruptions on the floor and improve patient safety.

Use of adjuvants, such as pharmacologic therapies, is encouraged; however, in many scenarios this is not an option. While there is no known scoring system to determine high-risk in-hospital behavior, several "red flags" may help physicians risk stratify the need for imposing limitations. Red flags include prior inappropriate behavior while hospitalized, altered mental status after visitation from friends or family, possession of contraband found during admission, and lying to health care providers about their history and behaviors. Concerns about ease of access to IV injections often lead to rules for patients like Ms A; however, as in her case, enforcement of rules can create friction between patients and providers and decrease trust in the health care system.

How Can Providers Discuss the Need for and Application of Rules During an Inpatient Stay?

The Joint Commission12 recommends taking a compassionate approach to discussing smoking restrictions with inpatients—an approach that can be applied to other inpatient rules as well. Use of a nonjudgmental tone during the discussion is key, as is explaining the rationale behind the rule. Whenever possible, it is important to offer acceptable alternatives to facilitate adherence. For example, a patient who smokes should be offered a variety of nicotine replacement options. Also, consultation with addiction specialists who are knowledgeable in the care of these patients may help guide practitioners as to which therapies might be the most effective in mitigating addiction-associated cravings. When such approaches are utilized, patients may be more inclined to stay inside the hospital without using substances while obtaining the medical care they need. Addiction specialists can be critical in guiding hospitalists and general practitioners (of medicine and surgery) regarding appropriate medications and doses, as well as providing their expertise in motivational interviewing.

Most importantly, policies should be implemented evenly and fairly to reduce the patients’ belief that they are being discriminated against (as other patients are expected to adhere to a more lenient policy). Involvement of hospital ethics committees to assist in the formulation of these polices can be helpful. Furthermore, sharing the responsibility of enforcement among multiple providers and disciplines, instead of merely relegating this task to hospital security or nursing staff, can ease the burden and allow for more practical and consistent policy enforcement. It is essential to provide patients a clear, unambiguous message. Physicians and nurses need to apply rules consistently; otherwise, the relationship between patients and providers will be fraught with difficulty.12

One of the main reasons for instituting such rules, beyond keeping patients safe in the hospital, is to place patients on a path to sobriety. However, it is crucial that patients be provided with the tools to stay sober once they have been released from the hospital. Naeger et al13 found that only 17% of patients with a substance use disorder continued to engage in treatment within the first 30 days after leaving the hospital. However, by providing outpatient follow-up for substance use disorders prior to discharge, up to 54% of patients remained in treatment 30 days after discharge.14

Who Is Liable for Adverse Outcomes?

As mentioned previously, a major concern that arises for providers who care for patients who use IV drugs is the possibility of injection of substances through a hospital-placed PICC or peripheral IV line, which often leads to restrictions from leaving the hospital floor. Further, the presence of an indwelling IV line can facilitate injection of substances even when in the hospital (eg, while in the bathroom or the patient’s room). Patients may arrive at the hospital with substances or visitors may bring them during the hospitalization,15 which often prompts staff to search patients’ belongings and body cavities. However, another common concern of providers is the potential for liability when one of their patients who abuses IV drugs uses while in the hospital. Unfortunately, while this problem plagues health care providers, there is a dearth of guidance for management of those who abuse IV drugs. One option is to place patients in a video-monitored room to prevent surreptitious use of drugs through hospital-placed lines.

However, the issue becomes murkier, as was the case with Ms A, when the patient requests privileges to leave the floor. Without direct supervision, patients may be able to inject drugs through a PICC line. Any manipulation of the line can result in line-related infections, sepsis, and endocarditis.16 Adulterants (such as talc, cotton, mannitol, or heavy metals) used to process illicit substances can result in thrombogenesis in central veins. In addition, there is the ever-present risk of air embolism during IV injections.17 However, there is little information available about the liability linked with an adverse outcome secondary to a patient’s manipulation of the line and subsequent harm to themselves.

In ambulatory settings, doctors are being held liable (some facing civil suits and others even murder charges) for overprescription of opioids.18 Therefore, it is unclear how legal liability translates to the inpatient setting and how health system risk-management teams reduce liability risk.

When Is a Behavioral Contract Indicated?

Behavioral contracts have often been used by health care providers to assist with alignment of treatment goals and to strengthen the patient-provider relationship.19-21 While many patients partake in informal contracts with their providers, others are asked to engage in a formal written contract. The topics of such contracts include implementation of a healthy lifestyle, restriction of use of opioids, and agreements to refrain from suicide attempts. In inpatient settings, patients with an underlying psychiatric disorder are often requested to sign more formal behavioral contracts. These contracts can include clauses for urine toxicology screening. Such clauses offer flexibility to teams that are willing to allow patients to leave the floor but simultaneously remind patients that forbidden actions may be discovered. If accepted, this contract may represent a compromise among providers and patients. Contracts help to frame expected behaviors and the consequences of failing to follow the terms of the agreement; they should be written in language that the patient understands and reviewed with the patient and a member of the care team. However, contracts can introduce tension-filled power dynamics into the patient-provider relationship, especially when used inappropriately or in the incorrect patient population. Such contracts should be presented as therapeutic and not as punitive maneuvers.

A contract may be indicated if a patient’s behaviors are disruptive, ongoing, and modifiable. If the patient is acutely ill, or when family members or friends are the source of the disruptive behavior, a contract signed by the patient is less likely to be effective.

In addition, the consequences of violating the contract should be reviewed. In some cases, a provider might no longer prescribe opioids if a patient screens positive for use of an illicit substance. However, for some, termination of the patient-provider relationship may be more harmful to the patient’s overall health. Thus, the consequences of violating the contract should be considered by an interdisciplinary team before describing the consequences to the patient.

Contracts have been used for over 30 years in other clinical situations. For example, no-suicide contracts are often used in patients with thoughts of suicide. Despite their use, there are limited data on their efficacy; nevertheless, these contracts commonly remain a mainstay of multimodal psychiatric treatment.22 One study23 examining patient perceptions of suicide contracts during inpatient psychiatric stays viewed the contracts favorably. As such, behavioral contracts, when utilized in appropriate patient populations, may be helpful and viewed positively by patients.

Who Determines Whether Rules Are Needed or Applied?

In times of uncertainty, physicians are often called to a patient’s bedside to make decisions. In medical scenarios (such as when a patient’s blood pressure is "borderline low" and a decision must be made as to whether an antihypertensive medication should be given), a physician’s evaluation and decision is appropriate. However, when there is uncertainty about a patient’s safety, many physicians may not be adequately trained or knowledgeable enough to make decisions. In these cases, who should determine whether rules are needed or should be enforced?

The best person to determine the rules of the hospital unit may be the charge nurse, also known as the clinical nurse manager or specialist. One of the many roles of the charge nurse is to ensure patient safety. One study24 conducted focus groups with charge nurses about their roles. Some comments elicited included "I go in and make sure the proper fall precautions are in place and they (staff nurses) are aware of the steps we can do to reduce falls. If the patient has behavioral health issues, and there is a risk for leaving the facility, we work on making it safe for him or her as well." Several respondents commented that the charge nurse is the person to go to for questions about policies.24 Charge nurses have often been on hospital units for longer than most of the other staff, do not have individual patient care responsibilities, and often serve as mediators between different health care providers, patients, and families. Therefore, they could be well suited to manage the hospital unit, including enforcement of unit rules.

However, identification of the charge nurse as an implementer of policies to ensure safety is insufficient. Charge nurses should be specifically trained in this role, take the lead in the assessment of patient safety within each unit, and then spearhead the implementation of new policies.25 In addition, while the charge nurse would have the role of managing the rules of the unit, the implementation of the rules is the responsibility of the entire patient care team. For implementation to be effective, a clear protocol is needed that is communicated to all care team members so that patients are provided with a united front when issues arise.

An example of successful implementation of this process is a quality improvement project on the creation of a standardized safe-search protocol at a psychiatric facility.26 In this project, the clinical nurse manager led the effort, and the research team found that the units most successful with implementation were those in which the nurse managers were actively involved, the entire medical team was aware of the protocol, and providers were able to provide feedback to adapt the protocol to the needs of the unit.26

Where Can Providers Find Templates for Rule-Based Care?

The necessity for limit-setting for patients admitted to medical services is increasingly common, as tobacco use and substance use disorders parallel numerous medical diagnoses. As a result, decisions regarding medical care extend to the treatment of these concomitant disorders. In patients like Ms A, the rules regarding off-floor policies have not been fully established.

Unfortunately, neither the medical literature nor internal hospital protocols (namely that of the hospital at which Ms A was cared for) reveal principles to guide medical providers. As a result, both nurses and physicians are left to determine the appropriateness of off-floor privileges on a case-by-case basis, resulting in subjective bias in the treatment of patients.27 Although health care professionals and institutions are generally expected to supervise patients and treat some patients against their will (for involuntarily admitted individuals, in the case of Section 12 in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts), the intermediate surveillance of patients is ill-defined, as providers respect the principle of patient autonomy.

Once providers have deemed that a patient has the capacity to make decisions, formulating their permissions is difficult. While the Joint Commission12 has provided resources to guide the implementation of smoke-free policies and address cravings of those admitted to the hospital, guidance on the management of understandable frustrations of patients who feel they need a change of scenery or a cigarette is left up to health care professionals with the goal of minimizing the risk to patients while maintaining their autonomy.28 If accessible, it may be helpful to query an ethics committee with interprofessional membership (including physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and community members) with nonmedical expertise.

CASE OUTCOME

The treatment team allowed Ms A to go outside to smoke on 2 occasions with a behavioral contract in place. Unfortunately, 1 week into her hospital stay, she was found injecting heroin into her PICC while in the bathroom. After a room search, hospital security found a large quantity of drugs and syringes in her possessions. She elected to leave the hospital against medical advice rather than allow her belongings to be locked up for safe keeping. Given the outcome of Ms A’s case (ie, leaving the hospital against medical advice), the hospital’s ethics committee was not surveyed; however, such committees can be useful as a forum for discussion of complex issues.29

CONCLUSION

In summary, the management of patients with substance use disorders can be challenging, especially when it comes to complex issues such as allowing visitors (who appear to be bringing in illicit substances) and having off-floor privileges (where patients will be unsupervised). We recommend approaching the topic with compassion and explaining the rationale behind provider-enforced rules. We also recommend having a standard practice regarding rules applied to inpatients so as to encourage an environment of fairness that promotes patient-provider trust.

Submitted: June 15, 2018; accepted August 9, 2018.

Published online: November 8, 2018.

Potential conflicts of interest: Dr Stern is an employee of the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry and has received royalties from Elsevier and the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy. Drs Frank, Islam, Johnson, Lander, Sharma, and Wallwork report no conflicts of interest related to the subject of this article.

Funding/support: None.

REFERENCES

1. Ganoe WA. MacArthur Close-Up. New York, NY: Vantage Press; 1962:137.

2. O’ Connor N, Zantos K, Sepulveda-Flores V. Use of personal electronic devices by psychiatric inpatients: benefits, risks and attitudes of patients and staff. Australas Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):263-266. PubMed CrossRef

3. Reich P, Kelly MJ. Suicide attempts by hospitalized medical and surgical patients. N Engl J Med. 1976;294(6):298-301. PubMed CrossRef

4. Maldonado JR. Psychiatric aspects of critical care medicine: update. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(3):xiii-xv. PubMed CrossRef

5. Dionne M. Harm reduction: compassionate care of persons with addictions. Medsurg Nurs. 2014;23(3):195. PubMed

6. Hamilton M, McLachlan RS, Burneo JG. Can I go out for a smoke? a nursing challenge in the epilepsy monitoring unit. Seizure. 2009;18(4):285-287. PubMed CrossRef

7. Evans G. Addicted patients inject, infect their own IV lines. https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/138503-addicted-patients-inject-infect-their-own-iv-lines?v=preview. Accessed October 11, 2018.

8. Connery HS. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: review of the evidence and future directions. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23(2):63-75. PubMed CrossRef

9. D’ Onofrio G, O’ Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636-1644. PubMed CrossRef

10. Suzuki J, DeVido J, Kalra I, et al. Initiating buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized patients with opioid dependence: a case series. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):10-14. PubMed CrossRef

11. Ziedonis D, Das S, Larkin C. Tobacco use disorder and treatment: new challenges and opportunities. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19(3):271-280. PubMed

12. Joint Commission Smoke-Free Brochure. The Joint Commission website. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/Smoke_Free_Brochure2.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

13. Naeger S, Mutter R, Ali MM, et al. Post-discharge treatment engagement among patients with an opioid-use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;69:64-71. PubMed CrossRef

14. Trowbridge P, Weinstein ZM, Kerensky T, et al. Addiction consultation services: linking hospitalized patients to outpatient addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;79:1-5. PubMed CrossRef

15. Goel N, Munshi LB, Thyagarajan B. Intravenous drug abuse by patients inside the hospital: a cause for sustained bacteremia. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:1738742. PubMed

16. Mallon WK. Is it acceptable to discharge a heroin user with an intravenous line to complete his antibiotic therapy for cellulitis at home under a nurse’s supervision? no: a home central line is too hazardous. West J Med. 2001;174(3):157. PubMed CrossRef

17. World Health Organization. Management of Common Health Problems of Drug Users. 2009. WHO website. http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/idu/drug_dependence/hiv_primary_care_guidelines_searo.pdf. Accessed October 11, 2018.

18. Nedelman M. Doctors increasingly face charges for patient overdoses. CNN website. https://www.cnn.com/2017/07/31/health/opioid-doctors-responsible-overdose/index.html. Accessed October 11, 2018.

19. Volk ML, Lieber SR, Kim SY, et al. Contracts with patients in clinical practice. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):7-9. PubMed CrossRef

20. Sparr LF, Rogers JL, Beahrs JO, et al. Disruptive medical patients: forensically informed decision making. West J Med. 1992;156(5):501-506. PubMed

21. Lieber SR, Kim SY, Volk ML. Power and control: contracts and the patient-physician relationship. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(12):1214-1217. PubMed CrossRef

22. Garvey KA, Penn JV, Campbell AL, et al. Contracting for safety with patients: clinical practice and forensic implications. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37(3):363-370. PubMed

23. Davis SE, Williams IS, Hays LW. Psychiatric inpatients’ perceptions of written no-suicide agreements: an exploratory study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32(1):51-66. PubMed CrossRef

24. Weaver SH, Lindgren TG, Cadmus E, et al. Report from the night shift: How administrative supervisors achieve nurse and patient safety. Nurs Adm Q. 2017;41(4):328-336. PubMed CrossRef

25. Wilson D, Redman RW, Talsma A, et al. Differences in perceptions of patient safety culture between charge and noncharge nurses: implications for effectiveness outcomes research. Nurs Res Pract. 2012;2012:847626. PubMed CrossRef

26. Abela-Dimech F, Johnston K. Safe searches: the scale and spread of a quality improvement project. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2017;33(5):247-254. PubMed CrossRef

27. AMA Principles of Medical Ethics. AMA website. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ama-principles-medical-ethics. Accessed October 11, 2018.

28. Smith T. Wandering off the floors: safety and security risks of patient wandering. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/webmm/case/326/wandering-off-the-floors-safety-and-security-risks-of-patient-wandering#references. Accessed October 11, 2018.

29. Gallegos T, Mrgudic K. Community bioethics: the health decisions community council. Health Soc Work. 1993;18(3):215-220. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy free PDF downloads as part of your membership!

Save

Cite

Advertisement

GAM ID: sidebar-top